After observing the Eid-ul-Fitr last week, India’s nearly 200 million Muslims have presumably joined the din of elections. Straddling the two events, this is a modest, snapshot attempt to see what has seemingly changed and what has not.

Muslims are part of the 960 million-plus electorate. Issues peculiar to their community – sectarian violence, hijab, beef and much else – may remain high on the minds, but provide no clue about the impact they may have on the elections’ outcome. One can at best try to capture the mood discernible on Eid with the help of media reports, some confirmed and sourced, others being mere thoughts on social media and depending on records, draw some comparisons.

Not for the first time though, some newspapers found it both convenient, even advisable in the heat of the ongoing election campaign, to project not the politicos but film stars, on their front pages. Shah Rukh Khan was on the front pages greeting his admirers from the balcony of his Mumbai home: “EID Mubarak, Everyone.” This may have helped spread the message that Eid was “for everyone.”

This ‘everyone’ bit also seemed to go well with social media platforms to whom the traditional/mainstream media have ceded space. No-holds-barred reflecting there – serious, provocative, light or humorous – widens the discourse.

More non-Muslims than usual appeared to post Eid greetings to “my Muslim Friends”, conveying an unspoken empathy. The generally divisive hate campaign against this community or that, which has been on the increase, abated, even if briefly. The elections injected it back, though, by the time this is written.

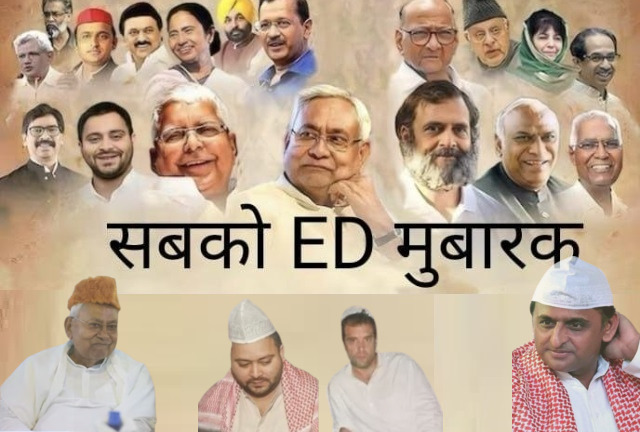

This was the first Eid when ‘Eidi’, the gift the Muslim elders give to younger friends and family members, got mixed with ‘ED’, the government’s Enforcement Directorate that is prosecuting many an opposition leader – selectively, the critics at home and abroad say, to disrupt their election campaigns. As the issue is debated in the highest court of the land, the Eidi-ED memes filled the social media.

A popular Bollywood actor thought of repeating an old caricature of a Hindu from Haryana greeting a Muslim acquaintance:“Bhai Tanney Eid Ki Ram Ram”. Irrespective of the occasion, unlike in the cities where people wish each other by the hour of the day, greeting someone with “Ram Ram” is common in the countryside, especially in northern India.

These were soothing touches amidst the poll-time rhetoric. “Ghar mein ghus kar martey hain (killing after entering homes) is surely meant for the terrorists and their mentors, which they rightly deserve. But when political opponents are accused of having a “Mughal mindset” and are lambasted for “eating meat during the Shravan month”, the connotation and the ambit of the remarks and their targets, get widened, at least in the public perception.

ALSO READ: What You Could Expect in Five More Years of Modi

Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh, the venue of anti-CAA protests by Muslims, and the political heat they generated some years ago, was this year the hub for food stalls during Ramzan. It rivalled the Jama Masjid area in the walled city. Food lovers of all faiths thronged both venues.

Muslims praying on open grounds is an old, often contentious issue. Delhi’s Lieutenant Governor VK Saxena expressed ‘gratitude’ that there was no namaaz on the road for the first time. He was happy that this helped the authorities to “ensure that any eventuality of a flare-up by miscreants or vested interests was averted.”

The times are changing. The politics of hosting Iftars which was once an important part of the Ramzan, went missing. Like the Shaheen Bagh protests, Iftar was disrupted by Covid-19. Now, with Hindutva in focus, political parties shied away from hosting Iftar parties.

In political terms, an Iftar party is aimed at spreading a message of communal harmony. Clerics, diplomats and political leaders rising above party affiliations would come together and break bread. Meant to facilitate the Muslims, they were attended by all. It created a sense of mutual trust.

Interestingly, diplomatic missions in New Delhi – the United States, Britain, Israel and Saudi Arabia among the many – continued with Iftars, while political parties, whether or not they marginalise the Muslim vote, were too busy electioneering.

The Samajwadi Party was known to host the biggest and best-attended Iftar party. Its founder Mulayam Singh Yadav would personally attend to guests. In earlier days his trusted aide Amar Singh supervised the catering. When Yadav was the Defence Minister, food came from Akash, the Indian Air Force mess. The menu on the table was lavish.

This year, Akhilesh Yadav, the present chief, party sources privately conceded, was wary of hosting an Iftar party lest his rivals brand him “anti-Hindu”. However, Akhilesh attended Iftaar parties hosted by others.

The Congress regularly hosted Iftaar parties earlier. In recent years though, the party has abandoned the tradition. Insiders claim it is short of funds, while critics blame it on its silently pursuing “soft Hindutva”. Its leaders vehemently deny this. But undoubtedly, the political parameters are set by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Iftar parties were started in Uttar Pradesh in the early seventies by the then Chief Minister Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna. Thereafter, they became an annual tradition. In the changed times, Bahuguna’s children are in the BJP.

The only time that the BJP hosted an Iftar party, old records say, was when Rajnath Singh was the Uttar Pradesh chief minister. He is now the Defence Minister. Other BJP leaders have avoided playing host on such occasions. The party as such views it as part of the Muslims’ ‘appeasement’.

What about the top dignitaries? Indira and Rajiv Gandhi hosted Iftar parties. So did Deve Gowda and I K Gujral. Leaders Ram Vilas Paswan, Rajesh Pilot, Jaipal Reddy and others played hosts.

One recalls the guests donning keffiyehs, turbans and ‘topi’ – like kashti, Turkish, Afghani – at Iftar parties Atal Bihari Vajpayee hosted at the plush Hyderabad House. Leaders of different faiths, diplomats and politicians of all hues attended. Vajpayee’s liberal face came through with his donning of green headgear.

The occasion was essentially for Muslims, but by the time they finished with the prayer to be able to break their fast, the food would be devoured and replenishments would be needed.

As President, APJ Abdul Kalam, a Muslim, if not hosting an official Iftar, would donate funds to some charitable cause or disaster fund.

The change began in 2014. PM Modi skipped Iftars hosted by President Pranab Mukherjee. And then, the practice ended. Electoral compulsions have set in as the ruling BJP calls it “appeasement politics” and condemn anyone who engaged in it. Its target this year was an ally, Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar.

Call it cynicism if you will. But the growing feeling of ‘otherness’ has led sections of the Muslims to think that the political Iftars of the past made the community too complacent to see through the ‘tokenism’.

The end of Iftar politics, applauded by those who support the present dispensation, is silently mourned by secularists who see it as an attack on India’s pluralistic ethos – the “Idea of India”.

Nazia Erum, the author of Mothering A Muslim writes: “Keeping it simple – the Iftar is meant to be a moment of spirituality. Ramzan and Iftar will come and go – but their achievement lies in helping you and your fellow human beings to introspect on how we are being led astray from loving and belonging together, by forces of politics and by the games of power.

To Erum, “The truth is, nothing would probably please God more than closing this gap of hatred and mistrust between fellow humans.”

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/