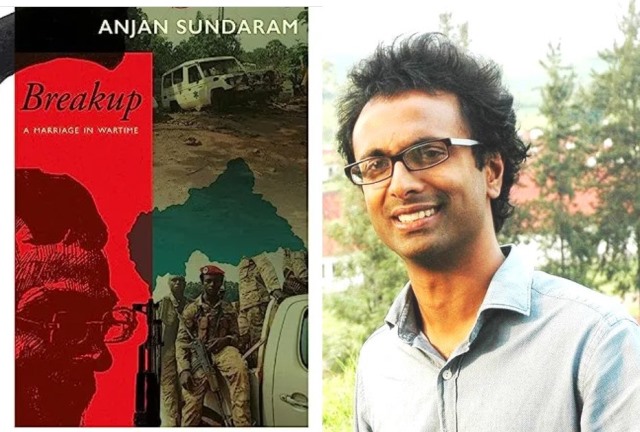

Africa’s Bloodied Fields And A Breakup

Anjan Sundaram, as a young journalist, tried to walk a different journey. After ten years of hard reporting from Central Africa for The New York Times, Associated Press and others, he chose to live a quiet life in a quiet town called Shippagan, Canada, with his little kid and loving wife. His wife too was a war correspondent/radio journalist in Congo, and, while she sent him quick radio messages from the conflict zone, he would file his stories. In a cosy house full of warmth and love, feeling the breath of his daughter on his face, he was happy. At least, he thought he was happy.

Then arrived the simmering unrest in his inner life, seducing him to an unknown journey trapped on the delicate edge between life and death, on a difficult and tough terrain. This was a journey surrounded by bloodshed and mass murder, treachery, hatred, the acidic smell of rotting bodies on the streets, hordes of pigs taking over a village, every man seemingly a killer and an enemy, and the acrid smell of sweat which stuck to his shirt like bad breath and perennial premonitions.

He rediscovered the Central African Republic, ravaged by a civil war, and where no one would dare to go and report. The reporter’s instinct was to go out there and write about it. The father and husband refused to accept this instinct. Nat, his wife, resolved the dilemma. She said, he must go. And that she too would have come along to this twilight zone, if it had not been for Raphaelle, their daughter.

Hence was born the book, Breakup: A Marriage in Wartime (Simon and Schuster, Rs 699, pg 185). Writes Noam Chomsky about the book, “A compelling journey of hatred and horror, of compassion and courage. I can hardly imagine the bravery it took to compile this invaluable record.”

Writes Sundaram, “The road forced me to look ahead, leading away from my anchor, but offering the potential of connection with strangers. I needed home, and wanted it, but gladly departed from it. And I realized that I had built my home because I was afraid, as a place in which to hide when I feared the world’s capriciousness.”

So there he was with Lewis, a dogged activist working for Human Rights Watch, Thierry, another journalist who was waiting for a chance to hit ground zero, and Suleiman, who, perhaps, turned out to be a spy for the ruthless and pampered Muslim generals, just about 15 per cent of the population, who were killing the majority Christians en masse, burning down their villages, and destroying all they could see, including petrol pumps.

The Christians had fled, but regrouped in the jungles as armed and impoverished guerillas, now in their thousands, launching fatal underground attacks on a jittery and ill-equipped Muslim army. They were waiting for their time when they will overtake the country, and its capital, submerged in eternal darkness, Bangui.

The international fig leaf was thereby a predictable pattern. France, the African Union and the UN had sent their peacekeeping force – to protect the usurper-dictator and his stooges. Once a French colony, looted, plundered and ravaged, the French flag few atop Bangui’s airport, like a farce flying in the sky.

ALSO READ: The Afghanistan Papers Uncover A Dirty War

Writes Sundaram about the vicious musical chair, “The Republic had suffered five coup d’etat and various foul play since its independence from France in 1960. Barthelemy Boganda, the country’s independence hero, had died in a mysterious plane crash, some say, planned by the French. His successor, David Dacko, was ousted in 1965. His successor, Jean-Bedel Bokassa, was ousted in 1979 by the French, who flew Dacko back to Bangui and reinstalled him as president. Dacko was ousted a second time by General Andre Kolingba, who organized elections in which Ange-Felizi Pattase was elected, only to be ousted in 2003 by the former army chief of staff, Fracnois Bozize, who was then overthrown by the Seleka rebellion in 2013.”

Next destination: Gaga. A massacre in a Christian village. Unseen and unheard by the world. Reporting is not allowed.

“They asked, ‘Do people know what is happening to us’? It struck me how important it was, for them, that we had arrived here. They were hungry and injured, yet, they didn’t ask for food or medicines. They asked the same question that Holocaust survivors had put to those who liberated the Nazi concentration camps during World War! Did others know what happened to them? If others knew, there was hope.”

He moved from one guerilla zone to another in the forests, across destroyed homes, negotiating with Muslim commanders, quietly taking his notes on one massacre after another, while smoke and gunshots filled the air. He and his friends almost got shot by a 300-strong rebel army in the jungles, but they escaped, using bluff and bluster.

Once in a conflict zone, when shooting had stopped, “A group of schoolgirls appeared on the street, walking in a line, laughing, wearing their pink school uniforms. They carried note-books on their heads and held plastic lunch boxes. They made the boulevard feel calm.”

Reading this passage, I was suddenly reminded of Srinagar in curfew, after the army clampdown in August 2019, mobiles jammed, media censored, internet shut, traumatized and isolated people in the Valley, total silence, and the beautiful Dal Lake condemned in an expanse of rippling loneliness. One morning, as I tentatively ventured out, a group of schoolgirls crossed the street. “Good morning,” they said. For a solitary and sublime moment, the world had suddenly turned sweet.

There were moments of redemption for Sundaram. There were brave and angelic human beings on both sides, who supported people beyond religion and faith, unafraid amidst the terror of death, in terribly difficult conditions, against all odds. Most of them were killed once the rebels captured the capital. Anjan kept them close to his heart, as he turned back, to his home, and love.

Indeed, after the rebels attacked Bangui, of the 140,000 Muslims out there, only about one thousand were left. Rest were butchered, or, they fled. This time, foreign journalists dropped in, and western newspapers splashed the ‘story’ on front pages.

“Muslims’ bodies were dismembered like they were toys. The war became an international spectacle. The overt attacks had a purpose: to publicly eliminate Islam from the country’s national identity…”

In a dark irony, America, the Western nations, and the UN, termed the genocide – ‘ethnic cleansing’. A genocide would have meant immediate and urgent international intervention.

“Exactly 20 years before, in Rwanda, the US and UN had avoided calling a genocide a genocide, and so they didn’t send in the troops necessary to stop the killings,” writes Sundaram.

He filed his reports for the magazines. He told the entire story to Nat. He felt drained. Empty. The war had taken its revenge on the journalist.

The cold Canadian small town became too restricted and alienating. He had no friends there. Nat had become detached. All communication seemed to have frozen. He wanted to move again, perhaps to Cambodia. She did not want to leave her roots. The hell-fire of a ravaged landscape, embedded in his reporter’s notebook, had destroyed a beautiful relationship.

“How would I live? For whom? These questions had lost their simple answers, and even their meaning,” writes Anjan. “Would another anchor present itself, allowing me to moor myself, and from there, again live?’

(Anjan Sundaram is the award-winning author of Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship, and Stringer: A Reporter’s Journey in the Congo. He has also reported for the Granta, The Guardian, the Observer, Foreign Policy, Politico, Telegraph and The Washington Post. He did his PhD in journalism from the University of East Anglia.)