Devdas, The Show Isn’t Over Yet

As Hindu epics-based television serials Ramayan and Mahabharat gather encore from Indian audiences locked-in by Caronavirus, I wondered what could come next in reach, frequency and impact. My search ended with films based on the Bengali novel, Devdas, by Sharat Chandra Chatterjee. However, they are distant second by millions of miles, understandably, because Devdas is not an epic, nor does it preach any faith, ideology or philosophy.

Of the 20 odd films, one or two can arguably be called classics. Again, together they are no match to cinema, theatre, art and literature springing from the epics and other scriptures. Cinema and Devdas are but a century-old. None compares to, say, Hollywood’s Ten Commandments. But that would be digressing.

The novel or the films have not attained mass popularity because they end tragically. Readers/viewers find that depressing. Chatterjee who wrote this semi-autobiography in 1900 did not publish till 1917. He was embarrassed, as per his son, having written under alcohol’s influence. He thought it lacked maturity, although it remains his most famous work.

Devdas is a tragic triangle. Temperamental and timid by turns, the protagonist baulks when childhood love Parvati (Paro), entering his bedroom at night, proposes marriage. Blaming himself, but also her, for the ‘mistake,’ he takes to booze and to Chandramukhi, a courtesan. She loves him hopelessly but he, unable to forget an unattainable Paro, dislikes her, even as he depends upon her.

ALSO READ: Can DD Re-Run Sustain Epic Magic?

Devdas dominates child-Paro, even strikes her on the eve of her marriage. Class and caste divides of the 19th century Bengal determine his parents’ rejection of the alliance and hers retaliate by finding someone higher and richer, even if old.

This story of viraha (separation) and self-destruction ends with a nomadic and sick Devdas, keeping the promise made to Parvati of “one last meeting”, dies at her doorsteps. There is no reunion.

Devdas’ 20 odd film versions cover the Indian Cinema’s evolution. The first by Naresh Mitra, released in 1927, was ‘silent’. In 1935, four years after Indian cinema went ‘talkie’, its director P C Barua also enacted the lead. The very next year, he directed K L Saigal and Jamuna, captivating imagination of the pre-Partition India’s cine-goers with their acting and haunting songs. Barua was not done: the Assamese version came in 1937.

In 1953, Vedantam Raghaviah made Tamil and Telugu versions. Both had Akkineni Nageswara Rao and Savithri playhing Devdas and Parvati. Two decades later, Vijaya Nirmala directed and played Parvati in another Tamil version (1974).

In southern India, Akkineni’s depiction of Devdasu is considered the ultimate. Stories have it that for Bimal Roy’s Hindi version (1955), Dilip Kumar repeatedly watched the Telugu film. Purists think no actor can surpass their performances.

ALSO READ: Fragrance Of ‘Kaagaz Ke Phool’

Devdas inspired passion and continuity. Roy was Barua’s cinematographer. That it triggered several re-makes over a long period is remarkable. It laid the most significant milestones in careers of all concerned.

It’s difficult, also unfair perhaps, to compare different versions made in different times with varying literary, technological, artistic, even financial inputs. I venture to say – and I am not alone – that Roy, by now working in what became Bollywood, getting Dilip Kumar – reportedly for Rs one lakh, a ‘princely’ sum in those times — to pair with Bengal’s Suchitra Sen, and with Vyjayantimala playing Chandramukhi, Kamal Bose’ photography and S D Burman’s music, is the most significant version.

Devdas, following Jogan (1950), Deedar (1951) and others where Dilip Kumar played melancholic characters, sealed his reputation as the “tragedy king”. It caused him psychological imbalance. But it also inspired many a young aspirant to flock to Mumbai to act in films.

Translating a literary work on celluloid is never easy. Capturing Bengal’s countryside, providing the right musical notes from Baul to Mujhra, and of course, writing, played their respective roles. Roy, it would seem, got the combination right.

In one of this film’s iconic scenes, Chandramukhi pleads with Devdas that he has drunk excessively and more would harm him. Surrounded by bottles, he retorts in utter despair: “Kaun kambakht hai jo bardasht karne ke liye peeta hai… main to peeta hun ke bas saans le sakun.”

I am unable to translate these lines by Rajinder Singh Bedi. But they were more or less repeated 47 years later in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s 2002 version.

ALSO READ: Thappad – The Slap Is On Us

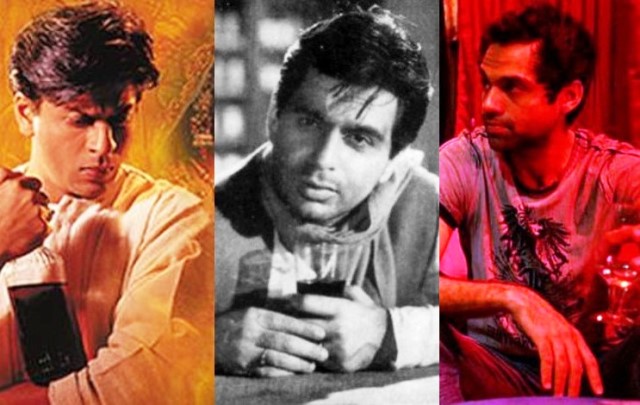

Unintended perhaps, there is continuity in the way Shahrukh Khan interpreted Devdas for Bhansali. Whether or not Kumar ‘learnt’ from Akkineni, Khan certainly emulated Kumar with whom he shares not only looks, but also ethnic/cultural roots. Think of the two Pathans hailing from Peshawar, interpreting a Bengali ‘bhadralok’!

This ‘flexibility’ explains Devdas’ larger South Asian literary/cinematic reach, unaffected by India’s Partition. It has been filmed twice each in Pakistan (in Urdu 1965 and 2010) and Bangladesh (in Bengali in 1982 and 2013). But it remains essentially Indian, with versions in Bengali, Hindi, Malayalam, Telugu and Assamese. Most “non-Bengali” versions have been made post-Partition.

Generations have embraced Devdas. My father loved Saigal’s portrayal. Post-independence generations go gaga over Dilip’s. But my son prefers SRK’s colourful bonanza. One of the most lavishly mounted Bollywood venture, it was the first Indian film to be premiered at Cannes Film Festival.

Sadly, I have seen only a few clips of Saigal. A Dilip admirer, I must confess to SRK’s interpretation growing on me as it were, on more viewings.

Film-makers by and large stuck faithfully to Chatterjee’s Devdas. But with the turn of the century, the current lot is taking artistic liberties. ‘Original’ Devdas went to Kolkata (then Calcutta) for studies. But Bhansali sent him to England, returning as a smoker, donning Western coat and hat. He lapses into dhoti-Panjabi ensemble when life gets tough and tragic. Incensed West Bengal lawmakers had demanded the film’s ban for its many ‘distortions’.

Among major actors of their times, besides Barua, Saigal and Akkineni, Kamal Haasan and SoumitraChaterjee played Devdas. Parvati and Chandramukhi have been interpreted by Pakistan’s Shamim Ara and Banglaesh’s Kabori Chowdhur/Sarwar, Vijaya Nirmala (also its producer), Vyjayantimala, Supriya Chowdhury, Sridvi, Aishwarya Rai and Madhuri Dikshit.

Vyjayantimala was known to have rejected the Best Supporting Actor nomination, insisting that her Chandramukhi, and not Paro, is the real heroine. Her view can be compared to Ramayan being viewed from Ravan’s standpoint, not always Ram’s.

On Suchitra Sen’s passing away in 2014, however, she admitted to being acknowledged at the national level and by critics after she played alongside Suchitra.

Ironically, save a brief frame, the two did not share a single sequence. While Vyjayantimala shot in Bombay, Sen’s part was filmed in Bengal.

For Madhuri who played Bhansali’s Chandramukhi with great aplomb, it was vindication. Clutching her Filmfare Award, she chided her critics who had written her off as a fading star after her marriage and migration to the United States.

Of Devdas’ five modern-day takes, in Anurag Kashyap’s “Dev D” all three protagonists are into booze and sex. The setting is Punjabi. His Chandramukhi is a hippy-like call-girl painting Delhi red.

In “Daas Dev” (2018) Sudhir Mishra borrows not just from Chatterjee’s novel but also from Shakespeare’s Hamlet to capture the dynamics of India’s dynastic politics.

In a sense, Devdas is India’s answer to Hamlet. Both have survived generations. Life does oscillate between hope and despair. Many would question their relevance today, though, especially their failure to rebel against prevailing norms.

The only known survivor of the 1955 saga besides Vyjayantimala, Dilip once stated that his aim was “to convey the sense of hopelessness that pervades the relationship between Devdas and the two women and others who are a part of his doomed life without leading ardent viewers to cynicism and despondence.”

The mystique continues. Gulzar’s 1980s attempt, with Dharmendra (who had reportedly financed the venture), Sharmila Tagore as Parvati and Hema Malini as Chandramukhi was aborted, nobody knows why. The National Film Archives of India (NFAI) is searching the two reels Gulzar completed, but are missing.

In early 1960s, India lost its treasure of old films, including Devdas, in a fire in a Mumbai godown. The NFAI engaged in protracted talks with its Bangladeshi counterpart to retrieve the only surviving copy of the 1936 version found with a Chittagong film distributor. It was exchanged for Satyajit Ray’s Apu Triology.

The recovery of Devdas, film analyst Gautam Kaul recalls, was aptly celebrated with a ‘premier’ held at Nandan theatre in Kolkata.

Great story-telling on cinema may elude in this era when a film-maker must stay commercially viable. Yet, last word may not have been said on Devdas.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com