‘Dhurandhar Effectively Exploits This-Is-New-India Flimflam’

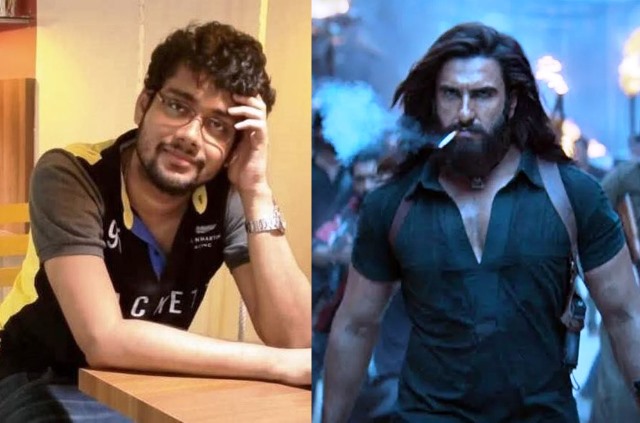

Amartya Acharya, a film critic and a senior faculty for 3D Printing Lab at Siliguri Institute of Technology, West Bengal, dissects Aditya Dhar’s political commercial formula:

The 210-minute film, directed by Aditya Dhar, is stirring up a plethora of opinions for justifiable reasons. Even if one considers Dhar’s one-film-old filmography as director and three-film-old producer-led films where the propagandistic tendency is clear, Dhurandhar stands out to me because of its genre trappings.

It is proficient in mixing the gangster film tropes with the espionage elements, following Hamza, a spy embedded within the Karachi underworld, investigating the nexus of the terrorist organizations, the ISI, and the underworld of Pakistan. The commitment to its world-building, in fleshing out the Lyari gang war and gang leader Rehman Dakait (played by Akshay Khanna), is quite praiseworthy, as is the film’s proclivity to build action set pieces without overuse of CGI and its indulgence in graphic violence.

What also makes the film work is its editing, whereby the 210-minute movie doesn’t feel bloated or inconsistent in its pacing. The chapter breaks—a Dhar staple—might help in identifying specific flaws within the film itself (the cartoonish portrayal of SP Chaudhury Aslam by Sanjay Dutt or Rakesh Bedi as a conniving political leader, the romantic subplot, which feels mostly unnecessary), but it also helps in maintaining a discernible and entertaining flow. It helps that the performances by a very talented cast, especially that of Akshaye Khanna as Rehman Dakait, and a restrained Ranveer Singh as Hamza, are remarkable.

However, the film stops short of greatness precisely because of its commitment to its messaging, the political bent it is clearly aiming towards, the sloppy integration of said political bent, as well as its use of footage of real events (audio and visual) to drive home its points. It is overt enough to be termed propaganda, without one discounting the craft that went into its making, a distinction that similar films of its ilk don’t enjoy.

The overwhelming narrative that is making Dhurandhar stand out even amidst the neutral audience is its somewhat realistic treatment as a film within the spy-gangster genre hybrid, a sharp 180 from the over-the-top, melodramatic, star-studded, James Bond-inspired films of the YRF Spy Universe, which is increasingly losing steam due to its heavily diminishing returns (War 2, also released earlier this year, had been heavily panned by critics and rejected by audiences).

I say somewhat, because even if one takes the above statement as gospel, Dhurandhar boasts of an ‘item number’ and a ‘love track’, similar trappings that had led to heavy criticism of the YRF Spy Universe films from a large section of the audience.

What also contributes to its box office popularity is it being part of a series of hyper-masculine films comfortable in violence that Bollywood has been offering since 2023’s release of Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Animal. However, what makes it far different is its commitment to being squarely within the gangster genre, dealing with macho sensibilities, displays of violence, and paranoia.

There is a political commercial formula, part of a surge of political-leaning films, explicitly leaning towards propaganda that is heavily inspired by not just governmental policies but a majoritarian ideology that transcends common criticism being attributed to films like The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story, where the craft and storytelling of said films are very much in debate.

Dhurandhar becomes somewhat more insidious precisely because those common criticisms cannot be applied to and thus made to dismiss the film, and thus the methodology of integration of messaging becomes far more effective as a result, overt or otherwise. The criticism would then be countered by the film’s vociferous supporters’ argument about the truth of the events not being accepted by the ‘establishment’ (read the critics), and thus contribution towards the film’s box office would be even more pronounced simply as a reaction to those criticisms.

The success of this genre of films represents the shift of a narrative to a “new India,” where aggressive/muscular nationalism becomes the dominant tone, an appeal primarily stemming from the country’s previous portrayal of being a defensive or ‘soft’ nation. As depicted in Dhar’s 2019 superhit film Uri—The Surgical Strike, and his latest Dhurandhar, the statement uniting these two films—“Ghar me ghuske marenge”—is highlighting this new version of the country, not content to simply tolerate attacks on itself but rather respond in kind.

ALSO READ: The Beef And The Battleship

It flattens complex geopolitical or emotional issues into binary—good vs evil—ensuring that majoritarian anxieties get heavily highlighted. It allows for the audience to successfully participate in exclusionary sentiments guilt-free, framed as patriotism, or a contextualization of the truth that past films had failed to portray. Because their cinematic value is far more potent than other films of their ilk, the risk of entertainment and propaganda blurring becomes more prominent.

The comparison with Pathaan seems a bit misframed because both Pathaan and Dhurandhar are approaching the same element of patriotism from opposite ends. While Dhurandhar is insidiously peddling in majoritarian anxiety, Pathaan is trying its best to appeal to nationalism, either overtly or through the conception of the protagonist, without explicitly resorting to jingoistic tendencies.

I am going to go out on a limb and state that in terms of media consumption, the pandemic had been a great equalizer because it led to the dominance of streaming services, opening up viewers to regional content that satisfies the palate of the consumer far more effectively than Bollywood.

If one wishes to trace back to when the shift began, one can point to the overwhelming success of SS Rajamouli’s Bahubali duology, as the moment of imperceptible shifting. The pandemic became a great equalizer. Now, utterly exposed to the commercial-driven films of Telugu cinema, the content-driven stories of Malayalam films, the social messaging baked within the commercial templates of masala films that usually defines Tamil cinema, and other regional industries like the Kannada and Marathi film industries, the Indian movie-going palette would truly be diverse.

Bollywood, as a result of said diverse palette, as well as the proliferation of streaming-exclusive web series content, will undergo an identity crisis that it is still undergoing to this day. Other than a superstar like Shah Rukh Khan, who proved himself to be a major box-office draw in 2023, Bollywood has been failing in not just replicating its own successes; it is also failing in replicating masala filmmaking because the current crop of filmmakers are unaware and untested within the contours of mainstream filmmaking.

I would be remiss not to point out that in the race of box office, the mid-budget Bollywood film has almost disappeared. Filmmakers like Dibakar Banerjee find their films like Tees stopped from being released; films like Homebound, Humans in the Loop, Jugnuma, or even Nishannchi find themselves saddled with show times in the theatres, unfriendly to the audience, or with limited releases restricted only to metro cities, which results in the theatrical business of these films inevitably crashing out.

It is further compounded by the streaming services being far more reticent in showcasing artistic freedom ever since the controversy surrounding 2021’s web series Taandav, and thus streaming services censuring films from their catalogue, or indulging in safer, more traditional content with a barely discernible edge.

As told to Amit Sengupta

‘Summits Alone Won’t Make India AI Hub; Infra Push, Skill Development Are Key’

‘Flashy Parents & Reel-Crazed Minors Behind The Wheel Are A Curse On Road’

‘Social Media Addiction Is Turning Into A Mental Health Crisis’