From The Archives

Could the Golden Temple’s siege and potentially, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination, have been averted? Could India have avoided military involvement in Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict, and the assassination of her son, former premier Rajiv Gandhi?

Both were national tragedies with global fallout. India of the 1980s suffered these, two of the many, if-and-but moments that remind of Mirza Ghalib’s “yun hota toh kya hota”. They permit no solution, no finality.

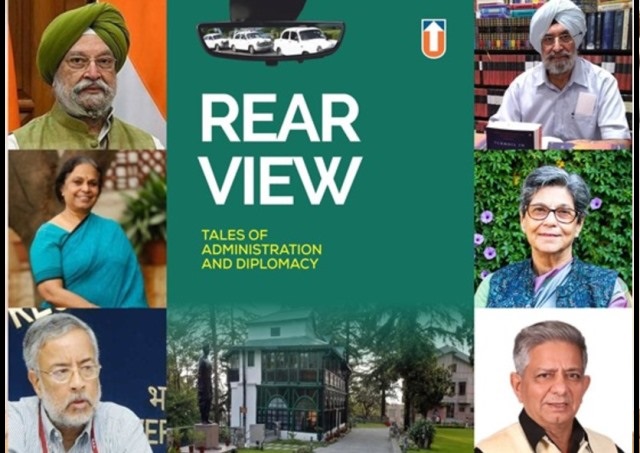

But they leave enough room for debate. Although not the top honchos, two young civil servants who manned key positions during these crises belonged to the “Class of 1974.” They offer their perceptions of what they did and what the country went through, after nearly four decades. Aptly named Rear View, as if from a moving Ambassador – no longer the “official chariot” – theirs are among the many “Tales of Administration and Diplomacy.”

The Punjab narrative comes from Ramesh Inder Singh, Amritsar’s District Magistrate from 1984-87. Serving on “ground zero”, he was conferred Padma Shri when only 36. He points to the fault lines from the political top downwards in governance, both civil and military before, during and after Operation Blue Star. Having stirred the divisive broth, Delhi lost control and hobbled from one mistake to another. This weakened the civil administration’s hold. As foreign machinations got underway, it involved the military in an essentially non-military and politico-religious task.

No single event has impacted the Indian polity as did this operation, he says. Terrorism ended in Punjab, but it reverberates in separatist slogans abroad. The once-cordial ties with Canada currently daunt India’s security-diplomatic establishment. An otherwise friendly Western world is poking India in the eyes.

Now a Union minister, Hardeep Singh Puri was Political Officer at India’s High Commission in Colombo, talking to the government of a wily JR Jayawardene and Lankan Tamil militants. All sides reneged on the accord that an inexperienced but earnest Rajiv Gandhi signed with Jayawardene. “Both peoples could have been spared this tragedy,” Puri writes.

India’s position became tenuous after Colombo and the LTTE reneged from the deal, making the Indian Peace Keeping Force’s position tenuous. The ‘misadventure’ in Sri Lanka bled India’s military and polarised Tamils in India, Lanka and diaspora in many countries. Eventually, none could prevent the mass killings that ended the Tamils’ resistance.

A dozen civil servants narrate fascinating stories of their contributions from hitting the ground during the emergency in 1976, to the “policy paralysis” of 2012, Vivek Mehrotra writes in the Prologue. Into their retirement, they provide valuable insights on how they met numerous crises, small and big while serving in districts, right up to state headquarters and in the union governments. Probably the first of its kind, the collection of essays recounts experiences, sweet, bitter and sour.

Former Union Health Secretary, Sujata Rao recounts the ‘prejudices’ against those inflicted with AIDS and the teething trouble while setting up the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO). On privatisation of medical education and ‘fairness’ of the entrance examination, she writes of what civil servants face in general: “Doing the right thing is often difficult as several stakeholders get affected when the wrong is sought to be set right.”

ALSO READ: Youth, Jobs And Disenchantment in India

Serving in Uttar Pradesh, Atul Chaturvedi laments about the ‘manipulations’ in admission to medical colleges. An angry outburst by the high court judges led to the clubbing of related disputes. Following the eventual Supreme Court verdict on health education, he indicates, some judges were transferred.

Ujal Singh Bhatia recounts the ‘unique’ campaign in the 1980s to save the environment in Odisha’s Phulbani. He writes of the women’s push for a ban on alcohol (an issue neighbouring Bihar is currently tackling). Ten rupees to the man would mean eight going to the ‘bhati wallah’ the hooch seller, thus “throwing the money into the well”, the women told him. “Women-centred programmes may be the accepted paradigm now,” Bhatia writes, “but in the Odisha of the early 1980s, this was new thinking, bordering on the sacrilegious.” Yet, one may see rickshaw pullers in Odisha towns crouched on their vehicles, stone-drunk.

Deepak Gupta pleads for reforms in the way the judiciary functions at the bottom asking, “Why should the poor suffer?” He stresses better magistracy and police administration while dealing with the dacoits, political protesters, communal tensions and situations of the officers when political regimes change.

C. Balakrishnan writes about having to fulfil family planning targets at the district level during the Emergency, “when the entire system was under the pervasive influence of the Crown Prince (CP) in the control of the then reigning Diva” when the CP’s Five-Point Programme was superimposed over the prime minister’s 20-Point Programme.

A ‘reluctant’ engineer-turned diplomat, Rajiv Dogra wrested a promise from a bigwig on the prize committee of the Nobel Prize for Literature that the Indian literary works would get “serious attention”. Thrilled that he could be serving the much-neglected Indian literature, he writes: “For a while, I imagined that I had won a Nobel myself.” But he baulked when most of the books he asked New Delhi to rush were old, dog-earned and some of them sub-standard works of the officials or their kin.

Bombay-bred Firoza Mehrotra had a cultural shock as a young lady officer in rural Haryana. Women justified being beaten by their husbands, citing the “saat phera” marriage ritual. Her explaining what those pheras mean was of no use in that patriarchal milieu. She was bluntly told by women she wanted to help that it was “ghar ka mamla” (a domestic issue).

Yet, the doughty officer did not hesitate to transport in her official jeep and accompany Chaudhary Devi Lal, Haryana’s highest-profile critic of the government. That was “Emergency within Emergency”, she wistfully records.

The general refrain is that governance has become “much more complex and the task of civil services much more difficult than when the 1974 batch joined service.” For one, globalization in general, India’s economy in particular, a reality now was but a subject of academic debate when these officials began. Social media has made a vast difference to their task.

Looking back, many unsavoury developments also occurred during the 1976-2012 period, including the Babri Masjid demolition, and a high number of sectarian violence. The batch of 1974 may not be culpable, but each of these events was the outcome of the failure of governance, of political leadership and the bureaucracy. Officials, some of them holding constitutional offices, took decisions that proved controversial, even detrimental. That trend persists.

For the few hundred who pass the UPSC exams, thousands do not, despite repeated attempts. On the other hand, many have done medicine, IIT and IIM before choosing to become administrators. The system needs to be reformed to avoid misuse to fulfil vaulting ambitions and form a nexus between personal and political. Any modern society needs good administrators, no matter more attractive and lucrative job avenues elsewhere.

In the last decade, which does not figure in the book, more than ever before, several officials and judges have taken calculated actions that are viewed as partisan and have then taken the political plunge.

The karmcharis are now expected to become Karma Yogis in the new era. The Capacity Building Commission is designing, the ‘Karma Yogi Competence Model’ based on PM Modi’s Mann ki Baat. The government hopes that the model’s implementation will transform the officer’s mindset from being a public servant to one “where service is done without any expectation in return,” says a report. For civil servants, serving and the future, it is time to ponder.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/