Glaring Chinks In Iron Ore Mining Policy

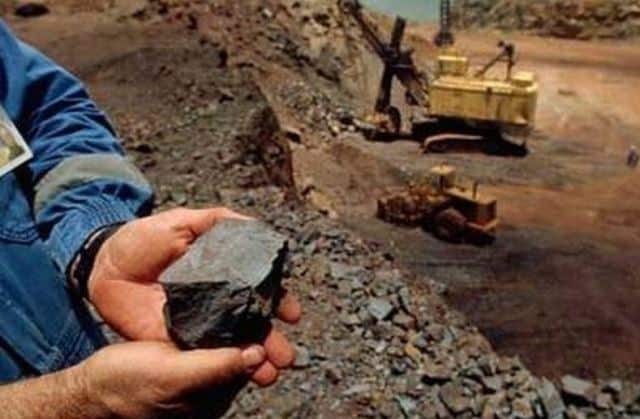

Mineral resources in India from iron ore to bauxite to coal are majorly found in remote centres of Orissa, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh where people, who hardly figure on the radar of the powers that be in Delhi, eke out a difficult existence unless they are employed by mining groups for ore extraction and allied works. No wonder then, when resources remain hidden under the earth and in the absence of their raisings, the places become fertile ground for spread of extremist movement or what is popularly known as Naxalism in India. The country’s mineral belts are generally rains deficient and the hard stony soil there does not support worthwhile crop cultivation.

The fragile peace that exists in the country’s sensitive mineral-bearing regions will be put to test as the leases of merchant miners of iron ore and manganese ore will expire on March 31, 2020 under a directive of the January 2015 amendment of the 1957 Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act.

In a questionable wisdom, the authors of the amended Act had for the first time made a distinction between merchant, captive and government groups owned mines. In what appears to be palpable discrimination, the 2015 version of the Act prescribes that while the existing leases of non-captive merchant miners are valid till March 2020 that of captive mines will remain in force till March 2030. What is more captive mine owners alone are given the right of first refusal when their mines are put up for auction.

As for Union and state government owned companies such as Steel Authority of India, National Mineral Development Corporation and Orissa Mining Corporation, they are allowed extension of existing leases for a period of 20 years at a time beyond the stipulated period of 50 years. Remember, ahead of 2015, there was no distinction between captive, non-captive and government ownership of mines. In every respect, including lease tenure, all three groups got identical treatment under the law. No longer so.

Discrimination part may or may not get set right by way of amendment of the 2015 MMDR Act. But what is of immediate concern is the large number of iron ore and some manganese ore mines owned by merchant groups that will stop operation on lease expiry in March 2020 making in the process thousands of workers unemployed. The same fate is awaiting many more thousands who are engaged in the long chain of logistics between mines and use of iron ore by steel mills domestically and in foreign destinations. This is to happen when the country’s unemployment rate is worryingly high and few new jobs are created with deceleration in economic growth.

Speak to minerals industry experts and they will tell you in one voice that there is no way the concerned state governments will be able to complete auction of the merchant mines whose tenure of leases will run out in nine months. Even assuming that auctions are held and successful bidders chosen, it will take them a long time, going by established patterns to secure all the sanctions, including environment and forest clearances (ECs and FCs) before they could start ore extraction. Yes, the Supreme Court has given a ruling that for auctioned mines that were operational earlier, the new lessees would automatically get ECs and FCs transferred to them from earlier lessees. But we are seeing new lessees’ frustrating wait for transfer of ECs and FCs for mines in Karnataka.

This correspondent on his recent visits to some Orissa and Jharkhand mines whose leases are to expire next March found workers and managers rattled by an unsettled future awaiting them. They have no clue as to whether the central government in view of the inevitability of anarchy setting in mining centres will do the sensible thing of extending leases of merchant miners to 2030 in line with captive mines or it will let mayhem happen.

The ground reality is this. It emerged at a recent mines ministry coordination cum empowered committee (CCECC) meeting that New Delhi has advised the concerned states to start auctioning mines expeditiously “so that the incoming miners have time to take preparatory steps to make the mines functional.” If any proof is needed, this alone is enough to confirm that the administration has no appreciation of the consequences of such a move. In fact, a recommendation of this kind could open a Pandora’s Box and the evils that will come out will be difficult, if not impossible to contain.

The law says: “On the expiry of lease period, the lease shall be put up for auction.” This means the concerned state governments can start the process of auctioning the iron ore and manganese ore mines only after their current leases expire in March 2020. There are other constraints too. According to rule 12 (gg) of the Minerals (other than atomic and hydrocarbon energy) concession rules, 2016 “a lessee is entitled to remove within six months after the expiry of lease period all or any one mineral excavated during the currency of lease, engines, machinery, plant …. and other works.”

Furthermore if a lessee is not able to remove all that is his, he will under the law get an extra one month to do so. The lessee, therefore, has a total of seven months after lease expiry to remove all his stuff, including mineral stocks.

In spite of the protection that current leaseholders enjoy under the law, the prospective bidders, emboldened by state governments, may seek to do due diligence of mines whose leases still have months to expire. An Orissa based mine owner says: “In that event, we most likely will go for legal recourse as due diligence by outsiders will interfere with our day to day operation. All mines stakeholders are living in uncertain times.”

An agitating issue for iron ore mines in Orissa and Jharkhand is the unsold pithead stocks of 127 million tonnes – 85 million tonnes in Orissa and 42 million tonnes in Jharkhand. The stocks are mostly fines of grades with iron (fe) content of up to 62 per cent for which there are no domestic buyers. Yes we can find buyers for the low grade ore abroad, particularly in China provided New Delhi will dispense with 30 per cent export duty on grades of up to 62 per cent fe content. The ill-advised export tax has robbed Indian ore of global competitiveness.

Some miners have made the suggestion that in the unlikely event of auctions going through, the successful bidders (lessees) should be “mandated” to pay to the existing lessees for pithead stocks “on the basis of last ex-mine grade-wise prices published by Indian Bureau of Mines.” But why should new lessees carry the cross of massive unsold stocks of departing mine owners, specially when demand for fines and low grade iron ore remain low. Will the government then remove the 30 per cent export tax on iron ore with up to 62 per cent fe content to facilitate pithead stock disposal in foreign markets? Export duty removal remains the budget expectation of the Federation of Indian Mineral Industries.

However covetous steel mills here unlike their counterparts in China, Japan and South Korea may be of captive mines, steel producers in eastern India without mines ownership are dreadful of the impending prospect of chaos engulfing the iron ore sector. Remember, working mines in Orissa and Jharkhand meet as much as 45 per cent of iron and manganese ore requirements of the steel industry in eastern India. According to rating agency India Ratings, iron ore production disruption following lease expiry will be around 60 million tonnes a year.