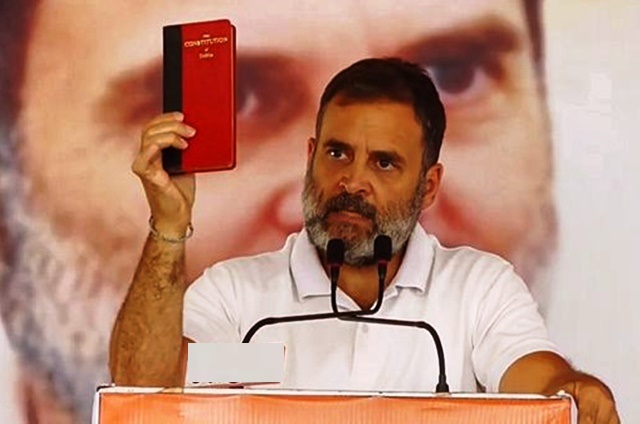

How Lok Sabha Elections 2024 Became a Referendum on Indian Constitution – II

Neither the BJP nor the Congress should be credited for making the Constitution an electoral issue. There was a third player behind the scenes who did not aspire to claim credit. It was the network of non-government organisations in India, loosely termed as the Civil Society. It started talking about the Constitution proactively after GE 2019 results and later embedded it in its core programme on ‘Constitutional Values’.

The Invisible Hand

It is contextual to note that the civil society that constituted the National Advisory Committee (NAC) of Sonia Gandhi during UPA-1 and UPA-2 governments had worked upon rights-based changes and brought in important legislations like Right to Food, MNREGA, Right to Information, Right to Education, etc. Post-2014, things changed fundamentally when the incumbent regime started using community rights to create communal conflicts. We could easily see this from the right to worship in Sabarimala case to the right to assemble and protest in JNU sloganeering and Kathua gangrape case.

Earlier, constitutionally guaranteed rights were aligned with ethical and moral considerations. After Narendra Modi led NDA came to power, his supporters started using rights for immoral and unethical concerns that created a culture of impunity for the violators of constitutional rights.

As feminist Ranjana Padhi writes in her seminal article, “In a sociological sense, a collective conscience is understood to have emerged when morally less critical societies gradually evolved certain basic beliefs and tenets, which they collectively affirmed as the highest common good. In the prevalent social and cultural ethos, there is the manufacturing of an altered collective conscience to suit a majoritarian agenda. This is being done by injuring, damaging, and reducing the worth of the “other”. This made-to-order collective conscience is employed at majoritarian will. The Preamble of the Constitution affirms “We the People” but the ascendance of majoritarianism is unmaking rules and laws for the “other’. Addressing today’s refabrication of the collective conscience requires discerning the strands of hysteria whipped up craftily each time”.

So, the myth of collective conscience post-2014 made rights-based regime almost redundant by turning it into a battle of identities and binaries. This not only disturbed the highest seats of power in the judiciary but in the civil society too, confirms Satyam Shrivastava, a forest rights expert and a social activist. He says, “Back in 2019 many social leaders and judicial leaders were deliberating on how to work upon constitutional values, not rights”.

There was an intense internal debate and deliberations in the civil society on how to translate an intangible thing like constitutional value into tangible action. And then came COVID, when all constitutional rights were suspended during lockdown in the name of protecting the citizenry from a deadly virus. It was an opportune moment in disguise for the civil society to change gears.

When things returned to normal, dozens of organisations started fellowships and training programs on the Constitutional values throughout the country. For example, as of date, more than 1700 fellows have been trained in constitutional values through various fellowships. These fellows are individuals, organisational leaders, community workers, activists, journalists and cultural activists.

He says, “If a single fellow would have talked to a hundred people, just imagine the impact of this initiative”! And the numbers are increasing. More and more NGOs and civil society organisations are now aligning their projects with constitutional values.

Satyam says, “It was heartening to see hundreds of social workers engaged in the elections in Maharashtra. I have just returned from my visit. I have seen people working day and night to ensure the participation of voters and educate them on the issues. They do not belong to any political party but they have taken the election in their stride”.

Most recently, Vikas Samwad, a non-government entity in Madhya Pradesh advertised its constitutional values fellowship for journalists. The stipend is handsome. A few organisations that have already run the fellowship are trying to build upon it by transforming the workshop content into digital form for wider dissemination. One such organisation We, The People Abhiyan is curiously named from the Preamble.

The Three ‘C’s

India Development Review (IDR) is Asia’s largest independent media platform that advances knowledge and insights on philanthropy and social impact. Halima Ansari and Saba Kohli Dave have rightly explained in their article on IDR that “constitution is a journey, not an event”. In their article, the writer duo suggest that “civil society and the government can ensure that constitutional values get translated into their work with communities on ground”.

This translation of Constitutional to Communitarian has many dimensions, one of which is Cultural. They write, “Connecting one’s local cultural heritage to the values in the Preamble is another way of nurturing acceptance of the Constitution”. This understanding was badly missing in the left-liberal intellectual discourse. Traditionally the left-liberal practice has been limited to the slogans of Qaumi Ekta and Ganga-Jamuni sanskriti. Even during GE 2014 when the fearmongering of Modi coming to power was at its peak, social activists were campaigning only in Muslim localities of Varanasi. They never cared to engage the Hindu voters.

This is one of the main reasons why the third ’C’ (culture) became a monopoly of the right-wing in the last few decades. The ideology of the RSS is called ‘cultural nationalism’. Any ideological counter to the RSS has always overlooked the element of ‘culture’ and primarily focussed on economic and political factors. Due to this, social activists have consistently faced hurdles in engaging with the everyday socio-cultural practices of majority of people and communities. We have witnessed a spate of attacks on social activists and journalists in the last few years on issues ranging from emotional to cultural. On the other hand, socio-political space for engagement has also shrunk, not to talk of the dissent itself.

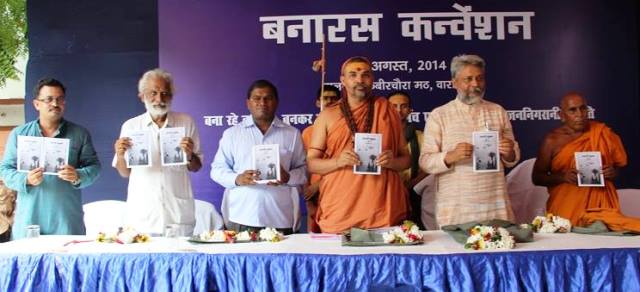

One of the initial responses to this ‘cultural’ crisis could be witnessed in Maharashtra but it was limited to Dalits and Pasmanda. In North India, a novel initiative was undertaken by Dr Lenin Raghuvanshi, a human rights activist of Varanasi, when he organised the Benares Convention in 2014 just after Modi came to power. This event was almost ignored by the civil society of Delhi. The well-articulated ideological context and background of the Benares Convention can be read here. He continued with the idea of blending the question of culture and constitution with his second initiative Neo-Dalit Convention organised just before general elections 2019. This convention saw the participation of a few prominent faces like Gujarat MLA Jignesh Mewani and senior journalist Urmilesh. Still, the question of culture remained an outcast in the civil society’s fraternal deliberations on Constitution.

Dr Lenin says, “We are dealing with corporate as well as communal fascism. The communal issue is not only inter-religious, it is intra-religious too. When communitarianism imagines its identity vis-à-vis the opposition of an ‘Other’, it immediately becomes communal. Therefore secularism also entails working on caste, class and patriarchal divisions within a community”.

This question of intra-religious secular practice was raised prominently in a couple of meetings organised by Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind in the run-up to General Elections 2024. With the events unfolding, this understanding has gradually seeped down the social activism circles recently. The now widespread constitutional value fellowships have helped a lot in emphasising the political significance of intra-religious communitarian work on caste, class and patriarchy.

The coming together of Culture, Community and Constitution is working, as we have witnessed in these elections. In Uttar Pradesh, the non-Yadav OBC and the non-Jatav SC block co-opted by the BJP in the last few years is now breaking away. This is the start of a new social formation. This, coupled with the disillusionment of the RSS cadre has enraged the BJP.

Change?

Winds of change may deceive too. With the 24×7 onslaught of reels, short videos and WhatsApp messages upon our collective minds, it is never easy to speak categorically about what our senses feel and much more difficult to comprehend what is being told to us.

All talk of ‘change’ started with the low voter turnout in the initial two phases. Both sides claimed that low voter turnout was in their favour, but somehow the snowball effect leading us to the last phase of polls has created some sort of consensus that the incumbent government is not coming back. After a series of Prashant Kishor interviews, veteran psephologists like Sanjay Kumar and Yogendra Yadav have made course corrections and now predicting around 250 seats for the BJP.

If the Constitution is a journey, elections are at most events. The final outcome of elections is always a situation that never changes the prevalent but rather consolidates it irrespective of which party comes to power. The process is significant, not the situation. In this regard, the electoral process of GE 2024 has been qualitatively different from all elections held to date. After the Constitution of India came into effect on January 26 1950 it has never been the question and issue of the masses. This election has challenged its inertness.

As INDIA candidate from Karakat, Bihar Comrade Rajaram Singh says in an interview with Dr. Gopal Krishna, “This election is a referendum on the Constitution”. This was a profound takeaway statement, but not the final truth because this is happening for the first time in India. This election is certainly the first referendum on the Constitution, but not the last.

The struggle to save the Constitution will continue on the ground. But hypothetically speaking- what if our government changes on June 4th? Will the need to save the Constitution end? The problem is more substantial. I would like to end by quoting Slavoj Zizek:

“How do we transform the basic coordinates of our social life, from our economy to our culture, so that democracy as free, collective decision-making becomes actual- not just a ritual of legitimizing decisions made elsewhere”?

(This is the concluding part of the series. You may read the Part I Here)