‘Labels Like ‘Traitor’ or ‘Patriot’ Do Not Sit Well With Real History’

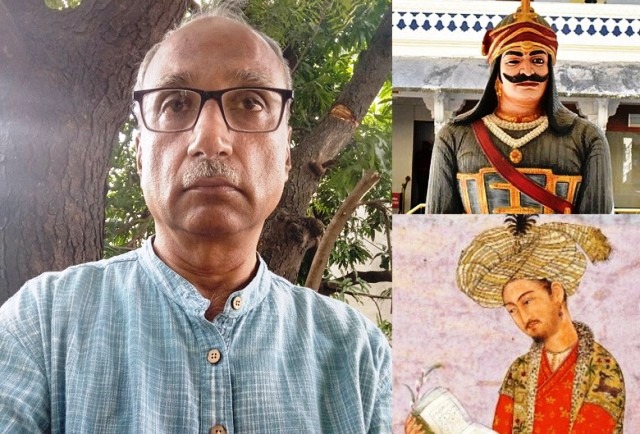

CN Subramaniam, a History scholar, says before passing judgement on a historical figure one must understand the political context of the associated era. His views:

Before passing any sweeping statement on the ongoing controversy over Rajput warrior Rana Sanga, I believe we need to understand the larger political scenario of 16th century South Asian politics and the political maneuvers of rulers of that era. The Afghans, Mughals, and also the Rajputs were essentially kin-based polities which were trying to develop some kind of centralised institutions so as to be able to gain control over an increasingly ‘commercialising subcontinent’.

Their main struggle was against their own kinfolk – on the one hand they tried to widen their own blood support by marrying into powerful families (Rana Sanga had more than 25 wives, if I am not mistaken, from different Rajput clans); and, on the other hand, they were trying to undermine the control of established kinsmen (as in the case of Ibrahim and Daulat Khan Lodi, Rana Sanga, and his brother, Prithviraj, and, Humayun and his brothers.)

The Mughals, incidentally, never called themselves Mughal, as it had a derogatory, tribal connotation. All rulers of the subcontinent had a multi-ethnic and multi-religious support system, as their own kin-based system was unreliable and insufficient. This could be in the form of inter-dynastic alliances, subordinate but friendly lineages, etc. So no one was purely Rajput, Lodi or Mughal, or Hindu or Muslim, in that sense.

As commerce revived in the 16th century in a big way, it was increasingly becoming imperative to establish larger political units to facilitate and reap the benefits of trade. Especially, these also needed a centralised administration, beyond tribal and kin-based controls. So they had to both expand their territories and internally centralise power. This, naturally, faced much resistance.

ALSO READ: ‘Reckless Remarks Against Rana Sanga Are Politically Motivated’

There was no notion of ‘insider’ or ‘outsider’ in the sense of being Indian and foreign. Or, for that matter, Hindu or Muslim, or permanent friends and foes. Salhadi Tomar of Raisen, a problematic ally of Rana Sangha in Khanwa, was well known for converting and reconverting from Hinduism to Islam and back. Everything was fluid.

Rana Sanga was trying to build a confederacy of Rajput clans under his leadership to expand his kingdom. Around the time Babur arrived, he had become a major contender for control over the key political centres of north India.

The Lodis were also a confederation of Afghan and Rajput clans trying to maintain control over the remnants of the Delhi Sultanate. Babur entered this scene — he had no kingdom worth mentioning, but he had managed to gain control over the segments of Changezi clans, and had powerful military hardware and strategy. He was betting on this.

Let us remember that Babur did not need any invitation to conquer Hindustan. He had no other option. But he could do with some allies — at least, temporarily.

Rana Sanga, likewise, may have hoped that he could divide the Sultanate territory with Babur. So he may have suggested a joint action against the Lodis. That is what emerges from Baburnama; and Nainsi, the Rajasthan chronicler, is somewhat reticent about Rana Sanga.

The references to Rana Sanga’s invitation in Baburnama is: “Although an envoy had come to us from Rana Sanga, the infidel, while we were in Kabul, and offered his support, saying, ‘If the padishah comes from that direction to the environs of Delhi, I will attack Agra from this direction’. I had defeated Ibrahim and taken Delhi and Agra. Uptill then, this infidel had done nothing. Sometime later, he did lay siege to the fortress known as Kandar…”

Evidently, the Rana refrained from attacking Agra when Babar was engaging Ibrahim Lodi in Panipat and preferred to wait and watch. He later began advancing towards Bayana and Agra which alarmed Babur and he decided to stop him. So, after all, Rana Sanga did move towards Agra, but after Babur had taken control of it.

The Battle of Khanwa was decisive in that the Rajput-Hasan Khan Mewati armies were trounced and decimated. Sanga had to leave the battlefield and was subsequently killed by his kinsmen and nobles. Mewati died in the battle. A son from a senior wife (Ratan Singh) became the Rana, but two sons of a junior queen went over to Babur to get control over Ranthambore, as promised by their father.

I don’t think labels like ‘traitor’ or ‘patriot’ are useful in this context. They were empire-builders and we need to judge them by what they set out to do, how much they could accomplish, and where they failed. As a matter of fact, all three, Babur, Lodi and Sanga did try – but failed. It was left to Akbar to accomplish the task – definitely, with the help of Rajputs, Indian Muslims and the Afghans.

(The narrator, popularly called Subbu, has worked with Eklavya, a path-breaking initiative in school education for developing social science curriculum, in close coordination with various state councils of educational research & training (SCERTs). He lives in Hoshangabad, Madhya Pradesh.)

I liked this write-up very much. So many take-aways from this- that identities were fluid, rather than rigid. Since the need of the hour was to build an empire and revive commerce, alliances of convenience were in evidence. So, multi religious support systems were often sought to be developed, transcending those based on kinship alone. For me personally, by far the best thesis here is the one that discounts the categories of legitimate/ illegitimate ‘owners’ of the land. So many of our disputes are actually rendered spurious if go by the arguments preferred in this article.