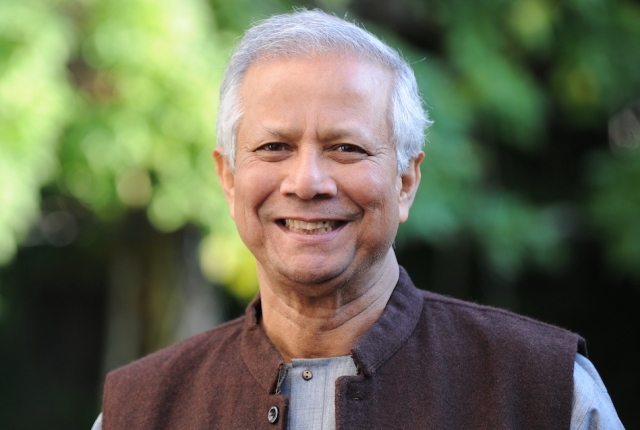

Muhammad Yunus: A Reformer or A Pariah

Myanmar is under military dictatorship since February 2021 when the army seized power in a coup. The unsavoury development that sent shock waves through the democratic world marked the end of a nearly decade of civilian governance in Myanmar, which is one of the poorest countries in the world. Expectedly but causing global outrage, the junta first detained her at home and then put the democratically elected Aung Suu Kyi in solitary jail confinement denying a frail lady medical care and right kind of food. The 78-year old woman seen as a symbol of democracy is nevertheless condemned to a jail term of 33 years after sham trial on charges ranging from corruption to violation of official secrets Act to unauthorized imports of gadgets.

The UN Security Council passed a resolution in December last calling for release of Suu Kyi and thousands of her followers. A host of countries, including the US, the UK and the European Union have imposed a number of sanctions, which, no doubt, are proving hurtful for the military regime. Now in an image improving move, the junta has reduced Suu Kyi’s prison sentence to 27 years from 33 years, as if the reduced sentence will ever again allow the politician to enjoy freedom.

If incarceration is the price Suu Kyi is paying for her campaign for democracy and human rights, there is a growing fear that the Bangladesh based economist widely known across the world whose ground level development work has lifted millions, the overwhelming majority being women who never had any access to bank credit or aware of their entrepreneurial skills, is not unlikely to meet the same fate as Suu Kyi.

Muhammad Yunus is facing a raft of allegations relating to tax evasions, receipt of funds from foreign sources without government clearances, tax evasions and violation of labour laws. What awaits Yunus will be known when the court completes hearing on the litany of charges against him. Incidentally, both Suu Kyi and Yunus are Nobel laureates. Suu Kyi getting the Nobel Peace award in 1991 for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights was a booster for those engaged in fighting autocracies and military regimes.

The same award was bestowed on Muhammad Yunus and his path breaking venture Grameen Bank in 2006 for their work to “create economic and social development from below.” But as the experience of Suu Kyi and Yunus will show a Nobel is no guarantee against persecution and harassment by the powers that be in some parts of the world.

Even in India, the management of central varsity Visva-Bharati will not stop complaining that Professor Amartya Sen (1998 Nobel economics laureate) whose maternal grandfather Kshitimohan Sen worked closely with Rabindranath Tagore in building the university has remained in “illegal occupation” of some land at Santiniketan in West Bengal. Is all this not happening because Professor Sen has remained steadfast in criticizing most New Delhi policies and persecution of minority communities?

Let’s see where the three countries stood in Press Freedom Index 2022 compiled by Reporters Sans Frontieres: India came 161 among 180 countries in 2022; the same year Bangladesh was at 162; and Myanmar was at a disparaginglyl low of 176. Across the world Press freedom is atrophying. But alarmingly more so in some countries helmed by illiberal regimes. We have recently seen attempts of muzzling and harassment of a group of Delhi based senior journalists after they published a report on Manipur based on a visit to the highly disturbed north-eastern state and interviews.

Enraged by the report saying that there are “clear indications that the leadership of the state became partisan during the conflict,” the police filed criminal charges against the journalists, including Editors Guild president Seema Guha for misrepresentation of facts. Whether it is Bangladesh or India, the democratically elected leaders at all levels are becoming increasingly sensitive to criticism that befit rulers seizing power by force or by staging coups. Democracies are expected to nurture civil society instead of circumscribing its space. But the culture of free debate, criticism based on facts allowing a hundred ideas (with apologies to Chinese Communist Party campaign of 195657) to flourish is fast disappearing in many places.

Not only that, the once celebrated social enterprises – Yunus earned celebratory status by championing the sector and running a global campaign that big companies should also have a social business on the side where the motivation will not be to earn profits but do good to those left out of development – and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) no longer find favour with the government. Over the years, many social businesses in developing countries have grown in size, become profitable and social influencers making them target for the politician-bureaucrat nexus to seek to control them. More and more NGOs are coming under scrutiny and their licence renewals are either postponed inordinately or denied. The worst happens as Yunus is experiencing if at any point social entrepreneurs betray political ambition. They may renounce that desire at some stage, but still they will remain suspect in the eyes of the authorities.

Why is prime minister Sheikh Hasina Wajed so hateful of Yunus – she doesn’t stop calling him names besides “bloodsucker” of the poor charging them extortionist interest rates – even long after removing him from the office of CEO of Grameen Bank in 2011? Isn’t it because Yunus dabbled in politics in 2007, however briefly that might have been when Bangladesh was under military rule and Hasina was in detention? The perception remains with Awami League and its supreme leader that he was propped up by the US and would do things to enable it to control the Bay of Bengal.

Yunus is painted as the villain for the World Bank reneging on the funding of the country’s most ambitious infrastructure project, a bridge on the river Padma linking southern districts with Dhaka, in 2012. In recent times, the economist had had occasions to tell the Press that he was not cut out to be in politics. Moreover, at 83 he cannot be imagined as a political risk.

ALSO READ: Food Security – Is Bangladesh Already There?

That, however, will not wash with Hasina government. Instead of getting any relief from the daily agony, Yunus is experiencing a rise in his persecution. The trigger for his troubles started over a decade ago when a Norwegian documentary alleged that the donations that Grameen Bank received from an aid agency in the Nordic country in the 1990s were diverted to a sister organization and then brought back as loans. In subsequent investigation by the Norwegian government nothing incriminating was, however, found. But then, according to Awami League government, Yunus has to clear himself of many other grave charges in the court of law. As it would be the case, global leaders, including former US President Barack Obama, former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and over 100 Nobel laureates have told Sheikh Hasina in an open letter that “one of the threats to human rights that concerns us in the present context is the case of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus. We are alarmed that he has recently been targeted by what we believe to be continuous judicial harassment.”

At the same time, a UN rights office spokesperson complains that “Yunus has faced harassment and intimidation for almost a decade… While Yunus will have the opportunity to defend himself in court, we are concerned that smear campaigns against him, often emanating from the highest levels of government, risk undermining his right to a fair trial and due process in line with international standards.” All this appeal is not, however, going to cut ice with Dhaka. The country’s law minister Anisul Huq while dismissing all such submissions as “unwarranted” sees these as “external interference in the country’s judiciary.”

Whatever happens to Yunus, the posterity will remember him for making microfinance available to millions of Bangladeshis, the overwhelming majority of them being women earlier never considered creditworthy. He can take credit for making poor women entrepreneurs by giving them small loans, which they make it a point to return. In an interview with Harvard Business Review published in December 2012, Yunus said: “Women used to hold less than 1% of bank loans in Bangladesh. So when I created Grameen, I wanted to make sure that half of the borrowers were women. But when we approached them, they said, ‘I don’t know what to do with money. I’m afraid of money. Give it to my husband.’ And I thought, ‘This is not the voice of the women. This is the voice of history, of the system, which created fear in their minds… We saw that woman borrowers brought so much more benefit to their families. Women want to build up something for the future with their money. Men want to spend it enjoying themselves. So we changed our policy to focus on women.”

It also goes to his credit that seeing how quickly microfinancing took roots in Bangladesh and liberated millions from poverty, illiteracy and bad health, many developing countries, including India replicated the programme with varying degrees of success.

When HBR wanted Yunus to react to the statement that “microfinance has also come under fire in recent years, he was blunt in saying: “The problem is not microcredit. It’s using the idea for the wrong purposes. Some programmes in India treated microcredit as an opportunity to make money. They blew it up and went to the stock market to float IPOs and so on. And that created all the tension… In some places even the loan sharks call their services microcredit. But we have no problem at Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, because microcredit has remained mission-driven. We want to help poor people. We don’t see them as an object for making money.”

Now Grameen Bank is firmly under government control. Yunus is old and there is no question of his again be associated with the organisation he created from scratch in any capacity. But let him not be hounded any longer. Let Dhaka listen to what world thought leaders are saying. Allow Professor Yunus to spend the rest of his life in dignity and peace.

What is happening to economist-reformer-innovator Muhammad Yunus in Bangladesh is highly disturbing. No question that the founder of Grameen Bank overstayed in the office well beyond the accepted age of retirement. But that is a common human failure, particularly of people in his age group. That beside, the government there has labelled many serious charges, including accepting foreign funds without official clearances, dodging of taxes and labour laws violation. Let all these charges be proved in court through fair and lawful process. Unfortunately, there is global fear as borne out by what more than one hundred global leaders and UN human rights body have said in their representation to the country’s prime minister that the judiciary is coming under pressure by the calumny spread against Professor Yunus. This is not good for democracy and the image of the country. Excellent article.