Operation Blue Star – When India Failed Punjab

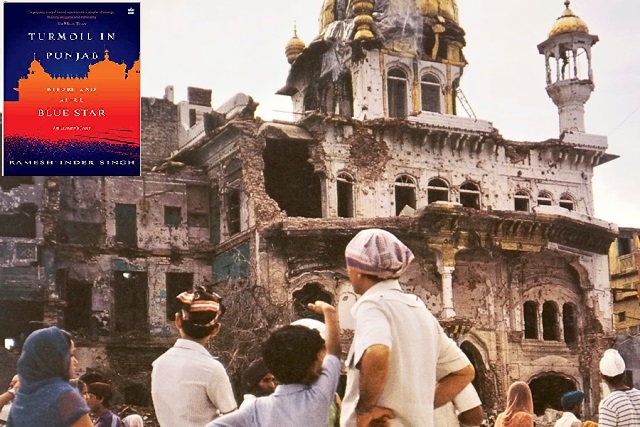

Of independent India’s many disasters, Operation Blue Star in 1984 must rank among the worst. It has left behind a legacy that nobody owns, and none has been held accountable.

“Blue Star was a disaster – ill-conceived, poorly planned, and terribly executed. Consequently, for the troops, it was a pyrrhic victory. A few hundred militants were killed. But their death sowed the seeds for ethno-religious nationalism to proliferate and generate violence far worse than what the operation had eliminated.

“Blue Star was not the epilogue, but a prelude to the violent struggle for Khalistan. The Army won the battle but at the cost of peace in Punjab,” Ramesh Inder Singh writes in Turmoil In Punjab: Before and After Blue Star, an “Insider’s Story”.

“It was a brutal time. The nation lost a Prime Minister, a former Chief of Army Staff, a Chief Minister, many ministers, leaders, and thousands of innocent citizens and of course some not so innocent, ” he notes in his 555-page work.

The writer was District Magistrate, Amritsar, during and after the various operations by the Indian Army against militancy, including Operation Woodrose and Operation Black Thunder I, and II. Which makes him an ‘insider’. He retired as Punjab’s Chief Secretary.

Singh is not the first to write. Many politicians, bureaucrats and generals have given their side of the story. It has been analysed by academics and security analysts, at home and abroad. Journalists, some getting vantage views, have recorded what led to 1984 and its aftermath. But his is perhaps, the first attempt at an all-in account.

His principal point is that while militancy was over by 1993, all the factors that caused it are present. He argues that militancy, which started with the Akali-Nirankari clash in 1978, was never a separatist movement for Khalistan.

He says the state lost the battle of perception. It failed to carry the community along. “This was, more than any other factor, the cause of the fatal consequences that followed Blue Star, and it continues to haunt the community even today”.

The civil administration, working on the ground was under constant pressure dealing with the diverse and fluctuating demands of the political class. It got compromised and governing Punjab became a nightmare.

As the events unfolded, he says, it became obvious that the Central leadership and the key military advisers were not conscious of the public sentiment or the political consequences of launching a direct assault on space considered sacred by millions.

It was a flawed strategy. No appeal was made to the militants to surrender. No attempt was made to negotiate to forestall the armed confrontation. The troops launched the attack suo moto. That left the trained, heavily armed and religiously motivated men with no option but to kill and die fighting.

Nobody comes out unscathed, untarnished, be it the politicians at the Centre or in the state; officials, both military and civil; the Sikh clergy and their Hindu adversaries; the media, the intelligentsia, and most certainly, not the militants with their varying emphases on tenets of the faith and on means they adopted. It was, and remains, a collective failure of a nation.

Imagine an India that hosted in a span of a few months of 1982-83, the Asian Games, the 7th Non-Aligned (NAM) and Commonwealth Summits, lapsing into a bloody turmoil in 1984.

Inevitably, the buck stopped at then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s desk. She reneged on softer, conciliatory options, including a deal worked out by Congressman Swaran Singh, brokered by Marxist leader Harkishan Singh Surjeet.

Although politically stable and most powerful then, she was not the Indira of 1971 when India helped Bangladesh’s birth and dismembered its principal adversary. Her advisors were no match to the earlier set.

ALSO READ: Bhindranwale – A Defiance That Refuses To Die

The book deconstructs the making of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale into a demagogue, as a counter to the Akalis, helped by Congress leaders Snjay Gandhi and Giani Zail Singh.

Diverse and even conflicting political factors coloured Indira’s decisions or their absence. Her government missed many psychological moments when it could have acted. She baulked when bold, potentially less damaging, options were proposed. Her prescription was no civilian casualties and no damage to the Golden Temple. Yet, both happened.

Blue Star was kept such a top secret that even the Intelligence Bureau director did not know. At the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) meeting in May 1984, Pranab Mukherjee opposed Army action but was overruled.

She first lost her way to the ‘why’ of the militancy and then, on the military action. She was hustled into both to block the “foreign hand”. Horrified — “Oh, My God”, she exclaimed – and rued that she had trusted those who promised a swift surrender.

She knew that she would have to pay a price. Her place in history was assured after Bangladesh. But Blue Star was different. Her idol now was Joan of Arc, the Frenchwoman who died at the stake. “One has to pay a price to find a place in history,” she told Chandra Shekhar, a fellow politician and future prime minister.

The Army lacked a Manekshaw who could refuse untimely action to the political leadership in 1971. It was inducted despite its earlier reservations. It stormed an enclosed structure, without intelligence on the scale of resistance. Sophisticated arms with unlimited ammunition with the militants and fortification of the shrine proved too formidable.

The militants’ defences were the handiwork of cashiered (some say, wrongly) Major General Shabeg Singh, the Army’s own hero-turned terrorist. Shabeg and Indira, although perched on extreme ends of a blood-soaked see-saw, underscore Punjab’s tragic irony.

The Army officially acknowledged 83 soldiers (four officers, four JCOs, and 75 from other ranks) dead, and 249 (13 officers, 16 JCOs, and 220 from other ranks) wounded. Although hardline Akali leader Simranjit Singh Mann claims 25,000 to 30,000 civilian casualties, Singh says the correct figure is 783.

He does well to place Punjab in the domestic and regional contexts to which, one must add the global one — that of the cold war’s hottest period. Was Punjab, like India, its unwitting player-cum-victim? Was Pakistan avenging the loss of its eastern province by promoting militancy in Punjab and Jammu and Kahsmir?

Given Zia ul Haq’s uncanny ways, the Pakistan factor did force India’s decisions in Punjab. But post-Zia, Singh claims, Pakistan was also part of the swift end of militancy. Benazir Bhutto shared crucial information on militants with Rajiv Gandhi in exchange for the withdrawal from Siachen. Later, she accused Rajiv of not keeping his commitment.

Pakistan’s ‘establishment’ couldn’t have relished this. Through the 1980s, its Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) simultaneously worked on promoting militancy in Punjab and the West-supported ‘jihad’ in Afghanistan, diverting resources from the latter to the former. ISI’s chiefs, Abdul Rehman and Hamid Gul scored successes on both fronts. Punjab militants would meet America’s favourite Afghan warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

How has India fared? Those responsible for the excesses, alleged or real, in Punjab and for the November 1984 killings of Sikhs, over 5,000 across the country, of them 3,000 in Delhi, have, by and large, gone unpunished.

The 1984 events impacted India as few others have. But Indians are particularly bad at reading their past. No lessons have been learnt. By the end of the same decade, moves began on how to deal with another minority, the Muslims, leading to the demolition of Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid in December 1992. That, again, led to more sectarian violence in 1993 and thereafter, in Gujarat in 2002. It is seemingly an endless cycle of actions and reactions.

And although there are no, or fewer, communal riots as per official records, compared to the last century, fear, polarisation, mutual distrust, the ghettoization of the minorities, and, partisan actions of the state in dealing with each of these issues, are there to see, provided one is sensitive and discerning.

Regrettably, 38 years after Blue Star, those who are currently engaged in putting their political stamp on the past and the present, as also those who are fighting to retain their ‘Idea’ of an inclusive, pluralist India, are both guilty of glossing over it. To put it bluntly, even their crocodile tears have dried up.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com