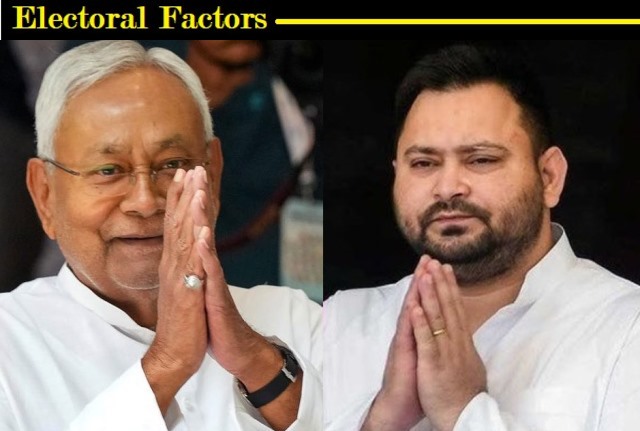

Phase 2 Will Test Bihar’s Rural Pulse on Nitish’s Doles and Opposition Cadres

As Bihar moves into the second phase of its assembly elections on Tuesday, November 11, the political contest shifts geographically and socially. Unlike the first phase, which largely covered the state’s core and central constituencies, the second phase stretches across the peripheral districts — the borderlands adjoining West Bengal, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and even Nepal. This expanse of 20 districts and 122 assembly constituencies represents the true countryside of Bihar — deeply agrarian, socially stratified, and politically charged in unique ways.

The sheer logistical scale of this phase is staggering. A total of 45,399 polling booths have been set up — 40,073 in rural and 5,326 in urban areas — for over 3.7 crore registered voters. The contest involves 1,302 candidates, all vying for the attention and trust of a voter base that has historically been unpredictable and often guided by local loyalties as much as larger political narratives.

This rural stretch, covering West and East Champaran, Sheohar, Sitamarhi, Madhubani, Supaul, Araria, Kishanganj, Purnia, Katihar, Bhagalpur, Banka, Kaimur, Rohtas, Arwal, Jehanabad, Aurangabad, Gaya, Nawada, and Jamui, will play a defining role in shaping Bihar’s 2025 mandate. The phase is crucial not merely because of its size, but because it sits at the intersection of several social and political crosscurrents — from caste alignments to ideological legacies and the growing influence of welfare economics.

The CPI(ML) Factor

At the heart of this phase lies the question of whether the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation [CPI(ML)] can maintain, or even expand, its influence in Bihar’s hinterland. The CPI(ML) is not a marginal force here; it is an organization with deep historic roots in the struggles of the landless and marginalized. Its presence in the Magadh region and adjoining districts such as Gaya, Arwal, Aurangabad, and Nawada is a continuation of the political legacy of the Naxalite movement that once dominated Bihar’s rural landscape.

Unlike most ideological parties that have faded under the pressure of electoral pragmatism, the CPI(ML) has managed to retain a disciplined cadre base and continues to influence the discourse on issues of land, dignity, and rights. In the 2020 Bihar Assembly elections, the CPI(ML) recorded one of the highest strike rates among the Mahagathbandhan constituents, winning 12 out of 19 seats contested.

The second phase, therefore, is not just another round of polling — it is a test of the Left’s continued relevance in Bihar’s rural politics. If the CPI(ML) performs strongly again, it would reaffirm that ideology still has a foothold in a political terrain increasingly dominated by caste arithmetic and welfare populism.

Mahagathbandhan’s Rural Confidence

The Mahagathbandhan, led by the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), is approaching this phase with confidence. The social fabric of the constituencies going to the polls — heavily dominated by backward classes, Dalits, and minorities — traditionally favours the alliance. The RJD’s Yadav-Muslim base, complemented by the CPI(ML)’s grassroots Left mobilization and the Vikasheel Insaan Party’s (VIP) EBC outreach, creates a potent combination on paper.

Particularly in Seemanchal districts of Araria, Kishanganj, Purnia, and Katihar, the Mahagathbandhan expects to perform well, given the large Muslim voter presence. However, as in 2020, there remains an unpredictable variable: Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM. If Owaisi’s party manages to split the minority vote, it could once again play spoilsport for the Mahagathbandhan, indirectly benefiting the NDA in closely contested seats.

NDA’s Welfare Pitch

For the NDA, led by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and backed by the BJP, this phase will test whether welfare schemes can outpace anti-incumbency and caste consolidation. A key element of the NDA’s rural pitch has been the ₹10,000 assistance scheme for women, which has reportedly reached a large number of beneficiaries in these districts. The BJP’s campaign narrative, amplified by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has focused on the government’s welfare outreach, infrastructure development, and law-and-order improvements.

However, the question is, will women voters stay loyal to Nitish Kumar, or will they vote based on local issues, caste preferences, and alternative promises? The outcome will serve as a referendum on whether cash transfers and welfare schemes have truly transformed voting behaviour in Bihar’s rural economy.

The New Entrant: Jan Suraaj

Adding to the electoral complexity is Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party, which, while not expected to win many seats, has become a symbol of political churn. Kishor’s campaign with its emphasis on governance, youth, and participatory politics has resonated among first-time voters and sections disillusioned with both major alliances. Even a modest vote share for Jan Suraaj could alter margins in a few tight races, making it a silent disruptor in this election.

The Stakes Ahead

The record 65.6 percent turnout in the first phase has already set the tone for an intensely participative election. A similar or higher turnout in Phase Two would indicate a motivated electorate eager to shape Bihar’s future. With counting scheduled for November 14, the outcome will not just determine who governs the state, but also reveal the shifting social and ideological currents in Bihar’s politics.

Ultimately, the second phase is as much about CPI(ML)’s enduring strength and the Mahagathbandhan’s social arithmetic as it is about Nitish Kumar’s welfare credibility and the BJP’s organizational might. The results from these rural heartlands will decide whether Bihar continues to vote by ideology and identity or whether a new narrative of welfare-driven pragmatism begins to take root in the state’s political soil.

(The writer is an established Author, Academic and President of the Centre for Reforms, Development & Justice)