Punjab: Partition to Protests

A brief history

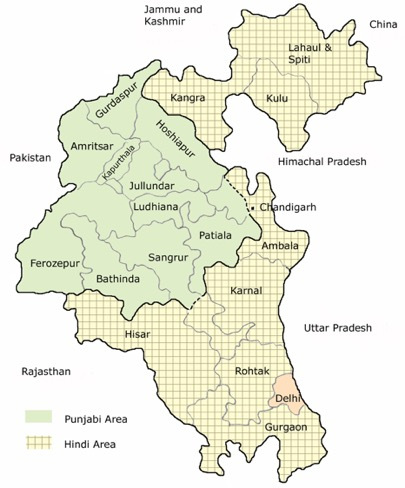

Punjab, the state of India, located in the north-western part of the subcontinent. It is bounded by Jammu and Kashmir union territory to the north, Himachal Pradesh state to the northeast, Haryana state to the south and southeast, and Rajasthan state to the southwest and by the country of Pakistan to the west.

The Indian State of Punjab was created in 1947 when the partition of India split the former Raj province of Punjab between India and Pakistan. The mostly Muslim western part of the province became Pakistan’s Punjab Province; the mostly Sikh eastern part became India’s Punjab state. The partition saw many people displaced and much intercommunal violence, as many Sikhs and Hindus lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east. Several small Punjabi princely states, including Patiala, also became part of Indian Punjab.

Punjab in its present form came into existence on November 1, 1966, when most of its predominantly Hindi-speaking areas were separated to form the new state of Haryana. The city of Chandigarh, within the Chandigarh union territory, is the joint capital of Punjab and Haryana.

People and Wildlife

With the growth of human settlement over the centuries, Punjab has been cleared of most of its forest cover. Over large parts of the Siwalik Range, bush vegetation has succeeded trees as a result of extensive deforestation. There have been attempts at reforestation on the hillsides, and eucalyptus trees have been planted along major roads.

Natural habitats for wildlife are severely limited because of intense competition from agriculture. Even so, many types of rodents (such as mice, rats, squirrels, and gerbils), bats, birds, and snakes, as well as some species of monkeys, have adapted to the farming environment. Larger mammals, including jackals, leopards, wild boar, various types of deer, civets, and pangolins (scaly anteaters), among others, are found in the Siwaliks.

Climate

Punjab has an inland subtropical location, and its climate is continental, being semiarid to subhumid. Summers are very hot. In June, the warmest month, daily temperatures in Ludhiana usually reach about 100 °F (upper 30s C) from a low in the upper 70s F (mid-20s C). In January, the coolest month, daily temperatures normally rise from the mid-40s (about 7 °C) into the mid-60s F (upper 10s C). Annual rainfall is highest in the Siwalik Range, which may receive more than 45 inches (1,150 mm), and lowest in the southwest, which may receive less than 12 inches (300 mm); statewide average annual precipitation is roughly 16 inches (400 mm). Most of the annual rainfall occurs from July to September, the months of the southwest monsoon. Winter rains from the western cyclones, occurring from December to March, account for less than one-fourth of the total rainfall.

Agriculture

Some two-fifths of Punjab’s population is engaged in the agricultural sector, which explains their heavy involvement in the Framer’s Protests over the new farm law reforms, which accounts for a significant segment of the state’s gross product. Punjab produces an important portion of India’s foodgrain and contributes a major share of the wheat and rice stock held by the Central Pool (a national repository system of surplus food grain). Much of the state’s agricultural progress and productivity is attributable to the so-called Green Revolution, an international movement launched in the 1960s that introduced not only new agricultural technologies but also high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice.

Aside from wheat and rice, corn (maize), barley, and pearl millet are important cereal products of Punjab. Although the yield of pulses (legumes) has declined since the late 20th century, there has been a rapid increase in the commercial production of fruit, especially citrus, mangoes, and guavas. Other major crops include cotton, sugarcane, oilseeds, chickpeas, peanuts (groundnuts), and vegetables.

With almost the entire cultivated area receiving irrigation, Punjab is among India’s most widely irrigated states. Government-owned canals and wells are the main sources of irrigation; canals are most common in southern and southwestern Punjab, while wells are more typical of the north and the northeast. The Bhakra Dam project in neighbouring Himachal Pradesh provides much of Punjab’s supply of irrigation water.

Home to the Farmer’s Protest

The ongoing farmers’ protest against the Narendra Modi government’s new agricultural laws isn’t just a battle to secure a legal guarantee for minimum support price or seek repeal of the three legislations. The battle is also to stop India’s rich capitalists from smuggling out farmers’ labour power without paying the cost – and there are several reasons why farmers from the Sikh community are at the forefront.

The Sikh farmers of Punjab were the first to grasp the danger when Parliament passed the three controversial bills in a great hurry, without a discussion or taking farmers’ unions into confidence.

In Punjabi diasporas, a number of politicians, singers, poets, and public figures have spoken up in support of protesting farmers, while in India, a huge number of Punjabi public figures have returned and rejected state-awarded accolades. Across the world, from California and London, to Vancouver and Melbourne Sikh Punjabi communities gathered in Covid-19 safe car rallies to protest in solidarity with Punjabi farmers.

The Punjabi efforts in the ongoing Framer’s Protests in India over the new Farm Law Reforms has put Punjab on the map, so it is time we start to learn more about its recent history since the partition.