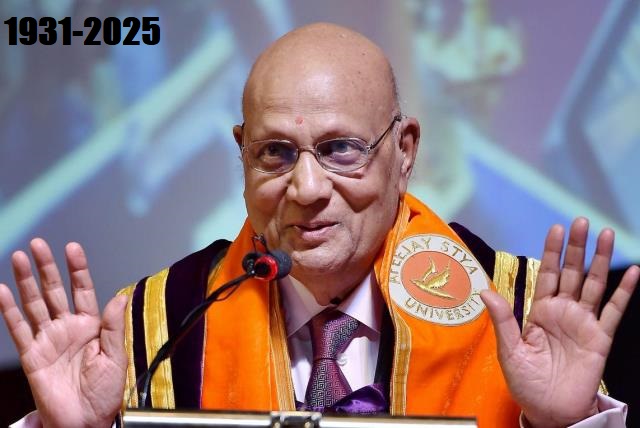

Swaraj Paul: Business Magnate & Family Magnet

Like many other celebrated family businesses in the country where the brothers will work together to make a success of their operations before going their separate ways for a number of commercial reasons and family compulsions, the four Paul brothers, namely, Stya, Jit, Swraj and Surrendra who together built a conglomerate with operations across India and a manufacturing foothold in the UK and the US decided to part ways in 1989.

What at that time surprised the corporate world was that the Paul brothers, who stood out for their camaraderie and their self-effacing traits would become independent of each other in running businesses. Their peers were left puzzled that the four brothers were able to separate businesses and assets not only amicably but at an amazing speed. Incidentally, the separation happened years before Swraj Paul, who passed away on August 21, was made a member of the House of Lords in August 1996.

The principal contours of the four brothers going their separate ways were: Swraj, who by then had made Indian promoters aware with small shareholdings of their vulnerability to corporate raids got Caparo group with all the UK and the US businesses. This was as it should have been. Afterall, Caparo was born because of Swraj making London his home following the tragedy of losing his four-year old daughter Ambika to leukaemia. In conceiving and building Caparo braving many challenges, specially securing lines of credit from banks, Swraj had the emotional support of his three brothers in India.

When the family worked as one, Surrendra made himself available to Swraj in building a steel tube mill in South Wales. Swraj was known to be generous in acknowledging the good work of others. Like we know from Jit Paul’s autobiography ‘The Business of Life’ that Swraj was much impressed by Surrendra’s “clarity of thinking and his commitment to doing things well at the lowest cost.”

Till Apeejay was split into three (Jit having no family of his own made a single unit with Surrendra), camaraderie and each living for the other three were the guiding spirit for the Paul quartet. Among the other shared principles were simple living almost being abstemious and fair business practices.

The question that was never answered by any of the four as to why they decided to go their separate ways. On hindsight, it would appear that the brothers believed that their children having brought up in an altogether different environment than theirs and in different cities Calcutta, Delhi and London, they might not be able to work as a team. Instead, the culture conflict among the next generation siblings could become the reason for undoing the gains of the past secured by hard work in trying circumstances.

Most likely, the decision to split businesses and assets was that of the family sage Jit who because of his self-abnegation nature could secure the approval of all without any hard bargaining. An example of what brotherhood meant for the Pauls was that Swraj because of his standing in Great Britain was assigned the task to negotiate the acquisition of three prized sterling tea groups, namely, Assam Frontier, Empire and Singlo.

The understanding then was Surrendra would run the tea business. And Surrendra had tea, among other things, in his portfolio when the separation came. The speed at which Apeejay businesses covering shipping, steel and engineering, overseas operations under Caparo flag, tea, Park Hotel chain, pharmaceuticals and real estate could be apportioned among brothers without any outsider getting an inkling of it left the corporate world surprised.

ALSO READ: The Enduring Legacy of Ratan Tata

Soon after the Paul brothers started working separately, industry doyen BK Birla told this correspondent: “I have known Jit Paul, a devout Gandhian, very well. Through his work over the decades and his commitment to the welfare of his three brothers and their families, he earned the moral authority to decide how to go about the separation.” Even as the Paul brothers started doing their business independently, they remained as close as ever. Expectedly, the same is not the case with the next generation.

All the four Paul brothers have passed away, Swraj was the last to go the other day. Except for Swraj, all the other three brothers were extremely media shy. Perhaps, this is a common trait with promoters of privately held companies. But Swraj’s coming into limelight was on the back of his spirited bid to take over the Shriram managed DCM and Hari Nanda controlled Escorts (since renamed Escorts Kubota), the two Delhi based powerhouses. Swraj’s buying of shares of the two companies from the open market, which well exceeded the respective holdings of the two families and his repeated attempts to get the shares registered upset business houses to no end since never in the past they faced a situation like that.

Before Swraj appeared on the scene, the Maharajas of India’s business controlled companies with small share ownership but they had a free run with tacit support of banks and financial institutions. The small shareholders had no voice in company affairs. Swraj wrote in his autobiography ‘Beyond Boundaries’: “Small shareholders in large public companies… had been virtually disenfranchised by managements.”

It was nobody’s case that Swraj by early 1980s had considerable wealth on his own account and moreover, he had access to institutional funds overseas. While that helped him to build critical holdings in DCM and Escorts to mount a challenge to the well-entrenched managements, the inspiration for the targeted hostile takeovers might have come from prime minister Indira Gandhi. But what Swraj didn’t bargain for was that Rajiv Gandhi would first lead him down the garden path to finally abandon him. “Buy DCM, buy Escorts… They are not with us and we should control them,” Rajiv told Swraj in April 1983.

If Swraj was close to Mrs Gandhi, Rajiv and Vivek Bharat Ram were schoolmates. Whatever it was, Swraj could never get his shares registered. Finally, he had to sell the shares incurring a loss of Rs15 crore. Since the DCM-Escorts fiasco, Swraj never again made attempts to gain control of an Indian company by either through hostile or friendly takeover. “Well, I didn’t have success with DCM and Escorts, the system was stacked against me. But I think, you will remember me for my contribution to obliging listed companies to make adequate disclosures and uphold corporate governance.”

Equally importantly, promoters of all major companies remain engaged in shoring up their holdings to fend off corporate raids. Finally, Khushwant Singh’s letter of July 29, 1996 to Swraj says Bharat Ram of DCM “now admits that what you (Swraj) were doing was quite legitimate.” The vindication of what Swraj was doing then comes from the target himself.