Orwell, like the authors of the other negative utopias, is not a prophet of disaster. He wants to warn and to awaken us. He still hopes – but in contrast to the writers of the utopias in the earlier phases of Western society, his hope is a desperate one. The hope can be realized only by recognizing, so 1984 teaches us, the danger of a society of automations, who will have lost every trace of individuality, of love, of critical thought, and yet who will not be aware of it because of ‘doublethink’. Books like Orwell’s are powerful warnings, and it would be most unfortunate if the reader smugly interpreted 1984 as another description of Stalainist barbarism, and if he does not see that it means us, too.

– 1984 by George Orwell, Afterword by Erich Fromm

When I first visited the Red Square in Moscow as a journalist, it was a sparkling, chilly night, and it seemed that I was living a dream. The beautiful St Basil’s Cathedral stood shining in splendid splendour, even as priests in ornamental robes burnt incense sticks, while in the pebbled expanse next to the River Moskva flanked by the walls of the Kremlin, all the memories of Soviet Russia which I had read as a student flashed by in a cinematic kaleidoscope.

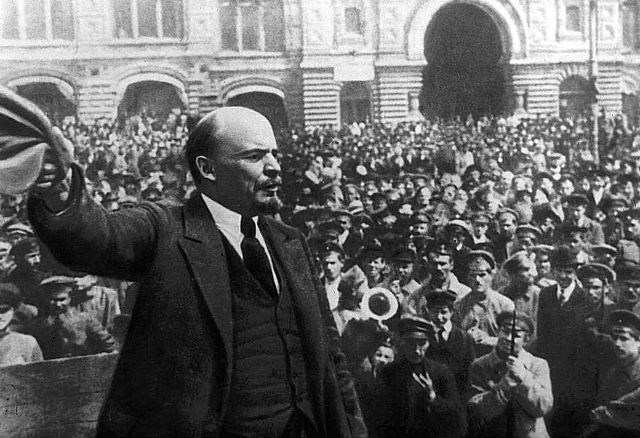

In the morning I joined the long queue at Lenin’s Mausoleum, with mostly Chinese tourists, even as soldiers paid solemn homage to the martyrs of the ‘War against Fascism’ nearby. Lenin was dressed in a black suit and tie. He was too still young and exhausted, when he died.

The night train took me to St Petersburg, formerly Leningrad (Lenin’s City), where the protracted and epical battle against the Nazi siege took place for months. Did 20 million people of Soviet Russia die fighting against the fascists, or many more? I think many, many more died defending their land, and the idea of revolution, with General Secretary Joseph Stalin at the helm.

Beyond the great art museum of Hermitage next to sublime River Reva in St Petersburg, the Tsarist palaces were on display, including the golden peacock. There are oral traditions of how the Bolsheviks entered the palace for the first time. You have to imagine the obscene opulence of the palaces to understand how the peasants and working class, oppressed, crushed and suffering, had no other option but to rebel.

This obscenity was multiplied a thousand times in the sprawling summer palaces near Peterhoff , next to the sea shore with Finland in the distance – glossy Italian architecture and the infinite luxury of cruel kings and queens who thought they were eternal and immortal. Indeed, if you read Russian literature of the times, especially Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy, you can measure the contrast between the existential suffering of ordinary times, the entrenched injustice, and the vulgarity of this unsurpassed hedonism before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

My visit was soon after the post-Gorbachev era; the times were heady, confused, liberating, with the economy having crashed. Soviet Russia had broken up. Glasnost and Perestroika was still in the air. Thousands of youngsters were crowding public places, drinking beer under the statues of Pushkin, and other greats, and next to the opera house where they would still play exquisite ballet; the young would talk incessantly, falling in love, celebrating a different kind of high. People could speak and loudly so, without the fear of being picked up, or spied upon.

Suddenly, I saw four communists, all elderly women in humble clothes, chanting slogans with a red flag at the Red Square – my heart skipped a beat. They were collecting donations in a tin box. I gave my bit – in American currency. They said, in a chorus, Red Salute! I repeated, surely, Red Salute Comrades!

At the Red Square, among the other revolutionaries, both Leon Trotsky and Stalin were missing. Bang opposite, a flashy mall loomed – it’s a new capitalism in Russia between the crony, the corrupt and the oligarch, the dead dictators and the latest, body-builder incarnation of the Tsar, a former KGB agent, ex-confidante of Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin. Now, a superstar. A new Stalin.

In her incredible collection of memories, footnotes, diaries, text, silences and anecdotes in the book, Second-Hand Time, writes Noble Prize-winning journalist, Svetlana Alexievich: “Twenty years have gone by… ‘Don’t try to scare us with your socialism’, children tell their parents… From a conversation with a university professor: ‘At the end of the nineties, my students would laugh when I told them stories about the Soviet Union. They were positive that a new future awaited them. Now, it’s a different story… Today’s students have truly seen and felt capitalism: the inequality, the poverty, the shameless wealth. They’ve witnessed the lives of their parents, who never got anything out of the plundering of our country. And they’re oriented towards radicalism. They dream of their own revolution, they wear red T-shirts with pictures of Lenin and Che Guevara.’”

She writes: “There’s a new demand for everything Soviet. For the cult of Stalin… A new cult of Stalin in a country where he murdered at least as many people as Hitler…Old-fashioned ideas are back in style: the great empire, the iron hand, the ‘special Russian path’…. The Russian president is just as powerful as the general secretary used to be, which is to say, he has absolute power. Instead of Marxism-Leninism, there’s Russian Orthodoxy…” (That she was born in Ukraine, tells a story.)

So does no one read anymore the stories of the Siberian death/labour camps under Stalin, as in that epical short novel called One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, by Alexander Solzhenitsyn? Is it so, really? Does no one read such literature anymore? Certainly, The Gulag Archepelago, they must have read that?

Or, do they read Dostoevysky, Anton Chekov, Anna Akhmatova? Nadhezda and Osip Mandelstam, the great poet – how did he die in the labour camp at Vladivostok in Siberia, and what was his crime? Why was Akhmatova hounded?

Writes Eric Hobsbawm in the Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century – 1914-1991: “In turning himself into something like a secular Tsar, defender of the secular Orthodox faith, the body of whose founder transformed into a secular saint awaited the pilgrims outside the Kremlin, Stalin showed a sound sense of public relations. For a collection of peasant animal- herding peoples mentally living in the Western equivalent of the eleventh century, this was almost certainly the most effective way of establishing the legitimacy of the new regime, just as the simple unqualified, dogmatic catechisms to which he reduced Marxism-Leninism, were ideal for introducing ideas to the first generation of literates… Nor can his terror simply be seen as the assertion of a tyrant’s unlimited personal power. There is no doubt that he enjoyed that power, the fear that he inspired, the ability to give life or death, just as there is no doubt that he was quite indifferent to the material rewards that someone in his position could command…”

Writes Ivan Krastev, from an East European perspective (The Guardian, September 4, 2022), “The German poet Hans Magnus Enzensberger labelled him ‘the hero of retreat’. But does retreat produce heroes? For most westerners, what is difficult to grasp is that the man who destroyed Soviet communism was one of the few genuine Marxists in the Soviet leadership.” “I still see Lenin as our god,” Gorbachev confesses in Vitaly Mansky’s film (Gorbachev. Heaven)

Krastev writes: “…He freed us from the psychological abyss that tomorrow is nothing more than the day after today… He did not free us, but he gave us a chance to taste freedom… There are groaning shelves of volumes written by political scientists, dissecting ‘what constitutes open and closed societies. Far less is written about the striking difference between coming of age in a society that is opening its shutters and coming of age in a society, even a relatively open society, in which the air smells of fear and stagnation. This first Gorbachev was not the hero of retreat, he was the angel of opening…”

Imprisoned several times, playright Vaclav Havel, who led the second Prague spring and became the first elected president of the Czech Republic, said, “Sometimes when I sleep I feel that I will wake up in a prison cell… Either we have hope within us or we don’t; it is a dimension of the soul… It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart; it transcends the world that is immediately experienced, and is anchored somewhere beyond its horizons.”