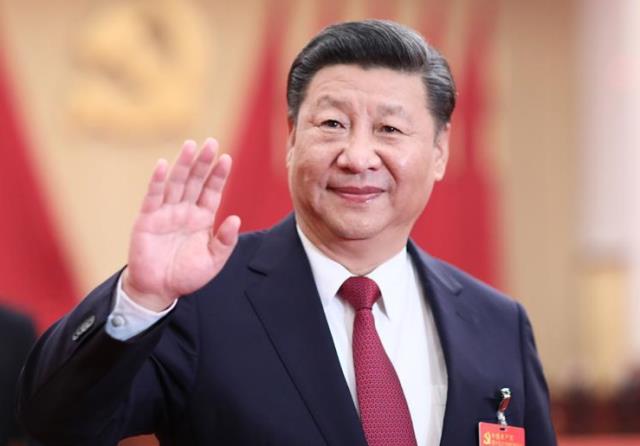

Xi Jinping’s Chinese Exceptionalism

China’s leader Xi Jinping’s legion of intellectual warriors are on a high, trying to fish out from the mainstream, “realists” — a pedigree of thinkers who have followed former leader Deng Xiaoping’s low-key pragmatism to spur Beijing’s rise.

The Utopian “China Dream” project, of railing the “civilisation state” on a path, which would lead to the recovery of China’s glorious past is apparently at the heart of Xi’s aggressive Wolf Warrior diplomacy, and the show of the flag.

It is the anachronistic idea of the “Middle Kingdom,” where China and its people are at the centre of a global system, of which a number of semi-independent “tributary states” are the moving parts, which appears to fire Xi’s worldview.

“The fact that the Chinese regard themselves as superior to the rest of the human race, and that this belief has a racial component, will confront the rest of the world with a serious problem,” predicted Martin Jacques, the author of the 2009 bestseller, “When China Rules the World: The Rise of the Middle Kingdom and the End of the Western World.”

Xi’s China Dream imagination, which embeds the idea of Chinese exceptionalism, was revealed during the Chinese strongman’s November 2012 tour of the National Museum in Beijing, in the company of six other politburo standing committee members, comprising China’s leadership core. In his remarks on the occasion, Xi made it plain that the “great rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation, was the greatest dream of the Chinese people in the modern era. He also pointed out the entire transition to China’s greatness would be marshalled by none other that the Communist Party of China (CPC), of which, he was the unquestionable leader for life.

Xi’s grandiose plan of spurring a “great rejuvenation” on CPC’s watch, is a sharp and disturbing detour from the ideological direction that had been sketched by Deng, who had replaced Mao Zedong, after his death in 1976. Deng’s worldview, on keeping a sharp focus on rapid economic development through market reforms, while keeping a low profile, in order to avoid geopolitical rifts, in its essence, was also inherited by his successors — Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

Both these leaders were essentially status quoists, and were by no means “grand visionaries” in the tradition of Mao and Deng.But the ambitious Xi has turned out to be far more unpredictable. In recent years, he has been revealing traits a hybrid leader–of aspiring to become a historic figure as important as Mao in shaping China– but also as an individual who has not lost touch with Deng’s economic realism.

Xi’s authoritarian line of thinking, in what he self-acclaims is the beginning of a “new era” on his watch, has deeper intellectual roots. By returning to Statism — an attempt to accomplish his Middle Kingdom fantasy driven by the Party-state, which exercises total control over people and politics — Xi has been echoing ultra-nationalist thoughts of intellectuals such as Song Qing. In a book published in 2009, Song, had ardently listed deep-seated grievances, which, he urged, his country was duty-bound to address and remove. He then demanded that China must emerge as a real heavy-weight on the world stage.

Xi has also been pursuing ideas of Yi Junqing, a disgraced Chinese politician, who has been a strong advocate for developing China’s soft-power. “The rejuvenation of our nation, also known as the “Chinese dream”, has been part of the country’s aspirations for the past few generations. However, without cultural power as a driving force, a country can not achieve true global competitiveness despite its economic and political progress.

China has become the second-largest economy in the world. But its potential for soft power projection has not fully exerted,” Yi once told China News Week.

Xi’s clearest articulation of the China Dream came through the two centenary goals, which he announced in October 2017, at 19th Party Congress — a twice-a-decade event. In a marathon three-and-a-half-hour speech at the conclave, Xi formally announced that by 2020, China would eliminate poverty and become a moderately prosperous society. Thirty years later, in tune with the centenary of PRC’s formation in 1949, China would emerge as an unrivalled, and advanced socialist nation in the world.

The project to establish a quintessential Middle Kingdom of the modern era would be accomplished then.But Xi also made no secret of his country’s aggressive intent. He has pointed out that in the journey to achieve greatness, China should be readied for epic confrontations, presumably with the United States and other holdouts such as India and Japan, as seen in the South China Sea and Ladakh to realise his Middle Kingdom dreams.

In his frenzied effort to realise the China Dream, and to smother any form of dissent in the internet age, Xi has pushed the party-state on the path of what can be called, digital totalitarianism. Consequently, Xi’s China has been proactive in using internet-based tools of mass surveillance, including face recognition technology, in tightly monitored social media content, and barricading by the “great firewall” of internet output flowing in and out of China.

In recent years, a new breed of establishment intellectuals have flocked around Xi, providing him the cerebral ballast to legitimise his authoritarian rule.

Trending among them is Jiang Shigong, a Peking University academic who had also earlier served in the Chinese government’s office in Hong Kong. In his essay titled “Empire and World Order” that has appeared on the Reading the China Dream, a website that translates works by Chinese intellectuals, Jiang openly advocates the “reconstruction of China’s civilisation” so that it can emerge as the centrepiece of a new “world order,” and, in fact, transitions into a new “world empire”.

“As a great world power that must look beyond its own borders, China must reflect on her own future, for her important mission is not only to revive her traditional culture. China must also patiently absorb the skills and achievements of humanity as a whole, and especially those employed by Western civilisation to construct a world empire. Only on this basis can we see the reconstruction of Chinese civilisation and the reconstruction of the world order as a mutually re-enforcing whole.

Another Peking University professor Chen Duanhong is a major advocate of statism, who cites Carl Schmitt, the German jurist, who provided some of the intellectual foundations for Adolf Hitler’s rise, as grounds for a new security law in Hong Kong. In a paper written in 2018 to define Beijing’s approach to counter Hong Kong’s challenge to mainland China, Chen quoted Schmitt: “The survival of the state comes first, and constitutional law must serve this fundamental objective.”

Some Chinese scholars are of the view that Chinese statism can be traced to the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

“Chinese/CPC statism began to come into its own after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the games having created a sense of pride and elation in the people, sweeping away the century-old image of China as the sick man of Asia, and China’s self-confidence burgeoned,” writes Deng Yuwen, in an essay “Chinese Statism, the Transitional Nature of Xi Jinping’s Regime, and America’s Response,” posted on the Reading the China Dream, website. Deng, however, spotlights t that the turning point for Statism to mature was Xi’s China Dream project.

In his article, he points to four stages which cemented Xi’s statism– the US-China trade war, the US attacks on Huawei, the Hong Kong protests, and the coronavirus pandemic. But the Chinese scholar is not sure how long Xi will remain in the saddle, despite the removal of term limits on his presidency in 2017.

“Accepting Mao’s lifetime rule taught the party and the people painful lessons, and that the highest leader would not rule for life is one of the most important shared convictions of the CPC high-level leadership, having become a powerful CPC tradition since the time of Deng Xiaoping. Even if other ‘good’ CPC traditions have been destroyed one after the other by Xi Jinping, this one cannot be lightly dismissed, and even someone like Xi Jinping cannot formally excise this clause from the written text even if in fact he winds up ruling for life,” he observes.

The growing friction with Washington has acquired dangerous proportions after two US aircraft carrier task forces were deployed in July at China’s doorstep in the South China sea. Simultaneously, on the diplomatic front, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s spoke at the Nixon Center, where he announced the futility of 50 years of engagement with China, setting the stage for a new cold war pitting Washington and Beijing against each other indefinitely.

The rise of the statist intellectuals, supporting Xi, appears to be edging out “realists,” including former senior commanders of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), who have essentially aligned their views with Deng Xiaoping’s lie-low-and-grow pragmatism.

But some from the Deng Xiaoping school have not thrown in the towel yet. On the contrary, they have mounted a fierce riposte to Xi’s confrontational approach toward US, warning that an underestimation of Washington’s military, technological and soft power heft could be disastrous.

Two old school hawks from the PLA’s stables have stood out in calling out for an urgent course correction.

In a July 5 article titled “2020, Four Unexpected Things and Ten New Understandings About the United States,” which appeared on the website guancha.cn Dai Xu, Professor at the Institute of Strategic Studies, at China’s National Defence University (NDU), has listed 10 concrete factors that explain why China will lose out to the Americans.

Dai asserts that China needs to urgently review its perception of the US. He cautions that unless Beijing changes its ideological understanding of the US, China will be in danger of committing serious mistakes.

The veteran General stresses that China should neither underestimate Washington’s power nor the patriotism of American politicians. “Do not think of Imperial America as a “paper tiger”. It is a “real tiger”, that kills people,” warns the General.

He adds, “Do not think of American politicians as gentlemen. They are not philanthropists. They are extremely loyal to their country and voters. They are not easily bought. They are only loyal to their voters. They will do everything to satisfy their voters.”

Second, the Americans are quick learners, capable of carrying out urgent course corrections, once they realise their mistakes.

“All Presidents have their own governing ideas and methods, but their principles remain the same. One of the significant characteristics of Imperial America is that once a national strategy goes wrong, a new government will make a 180-degree change to it without hesitation, changing their policies faster than flipping a page in a book.”

Separately in a May article that appeared in the South China Morning Post, Qiao Liang, a retired air force major general, and a professor at the NDU, warned that China should not attempt a military takeover of Taiwan, seeing the coronavirus pandemic as an opportunity.

“China’s ultimate goal is not the reunification of Taiwan, but to achieve the dream of national rejuvenation – so that all 1.4 billion Chinese can have a good life,” Qiao, said in an interview.

“Could it be achieved by taking Taiwan back? Of course not. So we should not make this the top priority. If Beijing wants to take Taiwan back by force, it will need to mobilise all its resources and power to do this,” he said. “You should not put all your eggs in one basket, it is too costly.”

But so long as Xi is in power, it is unlikely that, in the absence of a major upheaval, pragmatic scholars in the tradition of Deng can mobilise a critical mass to marshal the reigns of China’s intellectual power. Nevertheless, the dormant threat posed by the “realists” to the mainstream will remain open, for Deng’s influence on the Chinese psyche, notwithstanding the glossy attraction of Xi’s China Dream, runs deep.

The author is an expert on strategic affairs. (ANI)