A Tribute To The Fearless, Faceless Foot Soldier

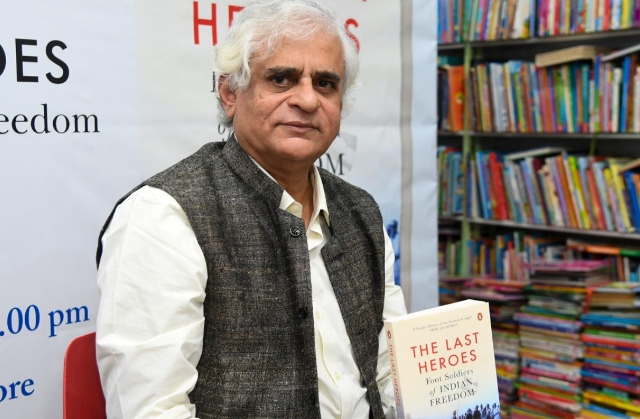

I write about P. Sainath not because we were colleagues at two news organisations, or to recall his winning many awards including the Magsaysay Award in 2007 for his outstanding reportage of rural India. Not even because I admire his approach to journalism, something I have not had the courage to do.

I write of him as he records something of great urgency in his latest book on the “foot soldiers” of India’s freedom struggle. They are those who have remained unsung, unrecognised and hence, unrewarded even as India celebrates 75 years of its independence from colonial rule.

The urgency lies in the fact that most if not all of these freedom fighters who gave their sweat and blood when young, may not be around by, say, the end of this decade. Six of those who feature in his book have died since May 2021. Bhagat Singh Jhuggian from Punjab, when assured that his role would finally appear in print, “let himself go” in satisfaction.

This came after long years of touring rural India to study rural conditions, especially the drought, and “extraordinary stories from the ordinary” about freedom fighters poured out from the larger exercise.

His book, Last Heroes: Foot Soldiers of Indian Freedom talks of those who did not fulfill the “seven laws of bureaucratic suffering” – the criteria for recognition for the freedom fighter’s pension. They may or may not have cared when young, but in the evening of their lives, they feel deprived of recognition, if not for garlands and funds, then for what they did, expecting nothing.

By a broad yardstick, freedom fighters recognised are those that are too well-known to be overlooked or those who have claimed. Those who do not fall in either category get ignored. Sainath records cases that are all from the rural areas – too isolated, too poor and perhaps, too shy and self-effacing to make claims.

Who and where have these freedom fighters been? Ironically, they have all along been amidst us. As Gopalakrishna Gandhi notes: “They come from across India and speak many languages. That diversity is mirrored in their individual struggles. With lathis, type-writers and tiffin carriers, they took on the might of the Raj. Some made bombs, others stopped and looted trains, and a young woman used a slingshot with great precision.” By interviewing over the years and writing about them, Sainath, he says, has “redefined biography.”

ALSO READ: Forgotten Fearless Women Of Freedom

Sainath cites historical evidence to assert that the freedom struggle was begun and fought in India’s countryside by farmers. Even the East India Company soldiers who revolted in 1857 were farmers-turned-soldiers. The early beneficiaries of Macaulay’s education were happy serving the British. Sadly, official history – British and now Indian – records only the kings and feudal chieftains and later, those who returned from England with an Oxbridge education. It has remained essentially urban and elitist.

Sainath’s heroes and heroines are men and women who made sacrifices when in their teens and twenties, during the 1930s and 1940s. He finds that women’s role has been ignored and discovers Demati Dei ‘Salihan’ of Odisha. Many like Hausabai Patil in Maharashtra who escaped jail or imprisonment lacked the proof required for formal recognition by the government; official recognition came only in 1992.

Captain Bhau of Maharashtra’s Satara and Sangli ran a “Toofani Sena”, probably parallel to Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (INA). At just 13, Laxmi Panda had cooked and fed INA soldiers in Netaji’s forest camp. She is not officially recognised. She asks: ‘simply because I never went to jail, nor fired a bullet but only worked in the forest camp, I was not a freedom fighter’.

He said in a recent interview: “Ketaki Parida, Hausabai Patil, Salihan – they all summoned up great courage. I keep asking myself – and I want readers to ask themselves – what would we have done in their situation? Yet, they are not going to be recognized as freedom fighters.”

There is a remarkable fast-forward to Baji Mohammad. A Muslim and a Gandhian freedom fighter wedded to non-violence, his skull was cracked in violence from Kar Sevaks at Ayodhya in 1992.

In another fast-forward, he disputes the claims whereby India’s freedom struggle is being dated back by 800 years. “We have had ministers dating back the struggle for freedom to the Delhi Sultanate and the so-called Muslim invasions.”

As a reporter for 42 years, he covered rural India full-time for thirty of those years. A series of 84 reports on drought published over 18 months published by the Times of India in 1993, were eye-openers that prompted some changes. They were later published as a book, Everyone Loves a Good Drought (1996). That fetched the well-earned Magsaysay and many other awards.

He headed the rural affairs section of The Hindu newspaper from 2004 to 2014.

Media in those days had not become what it is today. Sainath laments the media’s loss of perspective today. He contrasts its current role, with so many resources and technology, but serving only a small section of the people, with that of freedom fighters sending their message while publishing in adversity to the British rulers, their journals’ circulation barely touching from 500 to 2,000 copies. He has founded and edited the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), a digital channel of far-reaching significance in rural India.

He has shown a mirror to the Indian media that has unhinged itself totally from the ethos created by the freedom struggle. This would necessarily cover much of the so-called national media, from the big metros and the TV channels.

Echoing those he has interviewed, he said the country received ‘freedom’ from the British, but not ‘independence’ since the bureaucracy it earlier fought remained the same, enforcing British-enacted law with greater force. “I have learned from this book the great lesson of the difference between Freedom and Independence and the essential need to work towards coalescing the two,” Sainath says.

As time takes its toll on the little-known freedom fighters, Sainath says his book is written for “a generation that will never ever see, speak to, engage with, hear or listen to a genuine bona fide freedom fighter who gave them the country they now have. And that breaks my heart.”

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com