Bhagat Singh Practised Patriotism, Not Nationalism

The freedom fighter’s vision of a global federation of the future is still relevant today

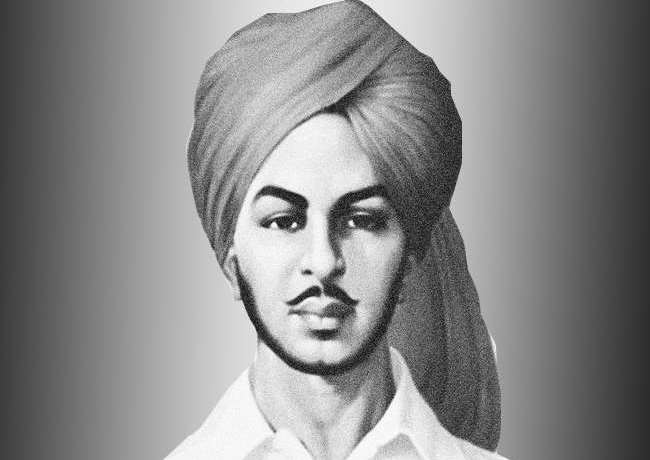

Seven decades after the British left, a young Indian donning a hat uncharacteristically continues to stride on South Asia’s mental landscape, ruffling up the political discourse and occasionally questioning the conscience of the former colonial masters.

Overshadowing his Sikh identity, Shaheed Bhagat Singh’s ‘Western’ image emerged when he was on the run from the British Indian police. His is among the most recognized face in the pantheon of freedom fighters.

He practised and preached patriotism, and not narrow nationalism as understood today; and socialism, not what goes in the name of social and economic reforms today.

Eighty-eight years after he was hanged, at all of 23 years, he would be perplexed today to be termed a ‘terrorist’ by some contemporary British historians, and at his legacy becoming a bone of contention among India’s warring political forces.

September 28th was Bhagat Singh’s 112th birth anniversary. Not many observed it. That Mahatma Gandhi’s landmark 150th birth anniversary soon followed may have something to do with it. Whether the people have fully understood the content and spirit of what the two said and did is a different matter.

Bhagat Singh’s anniversary was preceded by a stealthy, overnight, unauthorized installation of his bust in the Delhi University. The problem was that it was one of the three, with Subhas Chandra Bose and Hindutva pioneer V D Savarkar. Credit for it was taken by the students’ affiliate of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The university authorities played footsy till Savarkar’s face was blackened by students of the opposition Congress. Removing all three busts became inevitable.

The three represent differing ideologies. Savarkar’s followers in power today have sought to appropriate along with Gandhi the others as part of their establishment’s efforts to re-write history, especially of the freedom struggle. This is despite the fact that these lives are well documented.

Bhagat Singh’s records show that for a 23 year-old, some spent in jail, and as one who spent a year in college, he was highly committed, well-read, well-informed, knew several languages and left behind a body of work.

The narrative so far remains one of his being wedded to socialist and revolutionary ideas. But who knows, the process of appropriating him may never end, given, as analysts say, the “tussle between Bhagat and Bhagat Singh.”

In a new edited 638-page volume, historian and academic Chaman Lal says the process of Bhagat Singh developing as a Marxist revolutionary began with the setting up of Naujawan Bharat Sabha and the later rechristening of HRA (Hindustan Republican Army) as Hindustan Socialist Republican Army/Association. Founded in 1924, the HRA galaxy included Chandrashekhar Azad, Ram Prasad Bismil and Ashfaquallah.

Politically, he and his associates respected Mahatma Gandhi for the impact his ideas and actions created on the masses. But they did not believe that non-violence would yield the country freedom from the British.

Bhagat Singh and his comrades shot dead British policeman John Saunders. But they also smuggled a bomb into the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi and exploded it to create a noisy impact, without hurting anyone. If the first act was to send a stern message to the British, the latter was to arouse mass awareness for the same. Along with Sukhdev Thapar and Shivram Rajguru, he courted arrest, was tried on both counts and the three were eventually hanged.

The dual act separates him and his group from other revolutionaries who, in their own belief of no less significance, sacrificed their lives. He had evolved from his belief in the Ghadar Party’s adherence to violence to people-oriented activism based on socialist ideas.

Their hunger strike in jail added to mass awareness. From Gandhi to Jinnah to Nehru and Bose, all spoke in support. Some criticized them for their violent means to seek freedom. Chaman Lal says there was “not a word” from Hindutva adherents.

A controversy developed over Gandhi’s attitude to the death sentence on the three. Could he have bargained their exoneration before signing the Gandhi-Irwin Pact?

Chaman Lal told The Times of India: “Even if Gandhi had made it a point not to have the Gandhi-Irwin Pact without the commutation of their death sentences, the revolutionaries would not have accepted any compromise at their end. They had a clear perception that they had to sacrifice their lives to arouse the Indian masses for the freedom struggle. Yet one can say that Gandhi did make efforts but not with the passion of Nehru and Bose. Gandhi did not assert his moral position that he is against death sentence, whatever may be the crime. In the revolutionaries’ case, Gandhi should not have compromised on his principled position of opposition to capital punishment.”

Bose said that Bhagat Singh had become “the symbol of the new awakening among the youths.” Nehru acknowledged that Singh’s popularity was “leading to a new national awakening,”

Prof. Vinay Lal, Professor of History at UCLA quotes Nehru who thought “he had seen everything; but he had not, since, for a time, the popularity of Bhagat Singh appeared to exceed the popularity of Gandhi. He found that amazing.”

Singh and his comrades had rattled the British rulers. The three were hanged before the stipulated time to avoid mass protests.

In present times, his mystic endures. He is discussed by scholars and historians irrespective of their political credo. Numerous books have been written. At least seven films have been made between 1931 and 2002. Bhagat Singh’s role enacted by Shammi Kapoor, Manoj Kumar, Ajay Devgan and Bobby Deol has furthered the popular discourse.

At the political level, there is an unmistakable irony about Bhagat Singh’s portrayal as a socialist when socialism and indeed, Marxism, are on the back-foot in much of the world, even as caste considerations divide India’s socialists and the Marxists are being electorally vanquished.

Across South Asia, the Bhagat Singh mystique remains deeply embedded among the educated and discerning. Late Madeeha Gauhar of Pakistan’s Ajoka Theatre Group told this writer of several stage performances. To avoid any divisiveness, she said, the preferred image of Bhagat Singh is one of the clean-shaven man with thin moustache and fedora. The same endures in India.

Two bodies in Pakistan, Bhagat Singh Foundation and Bhagat Singh Memorial Foundation want a memorial in Banga, his birthplace in Lyallpur and a road named after him in Lahore, where he was hanged. One of them wants the British Queen to publicly apologize for the brutal treatment to him before he was hanged.

From Bangladesh, Farooque Chowdhury recalls that the slogan that Bhagat Singh introduced during the freedom struggle turned into a war cry of the exploited people across the Subcontinent seeking their rights: Inqilab Zindabad – Long Live Revolution.”

In a 1924 essay, Bhagat Singh embraced the ancient Indian idea of “vasudhaiva kutumbakam” (the world as family) and visualized a global federation of the future. If only a dream, it is still relevant today in a world that is witnessing barriers built in the name of nationalism.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com

Well written- shaheed Bhagat Singh was a great freedom fighter of Punjabi land , he stood up and fight against the British empire- he and his comerade served the land of India , gave their lives, that we can enjoy the freedom and be recognised in this modern world today . We should always remember shaheed Bhagat Singh as he serve the land of India 🇮🇳. His sacrifice has a great place in sikh history as well as Punjabi, we always proud of him and our generations , living in Punjab , India 🇮🇳 and abroad———-from— Parminder Singh bal , President, Sikh federation, uk