Geopolitical Answers – Through a Diplomat’s Pen

Ambassador Sudhir T. Devare is “not neutral” and, to use a unique phrase India has coined to explain its position on the ongoing Ukraine-Russia conflict, is “on the side of peace,” in whatever he has done as India’s official representative abroad. That is what a good diplomat is supposed to be.

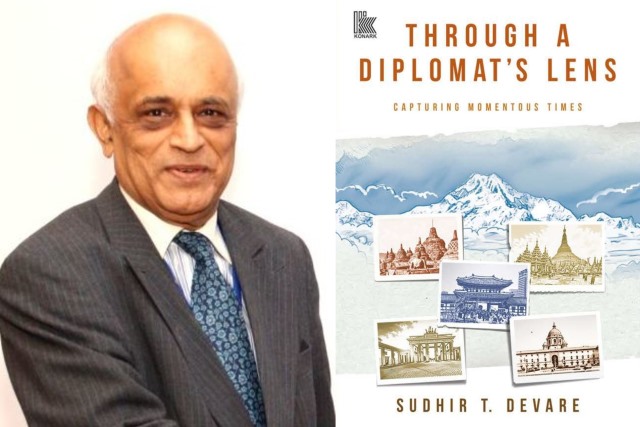

Having served in Moscow as a young probationer and when the USSR disintegrated, as India’s first envoy to Ukraine (concurrently to Armenia and Georgia), Devare feels a special affinity and concern. He devotes it the maximum space in his just-published memoir: Through a Diplomat’s Lens.

Pleading for an end to the “unending” conflict, he apportions blame on both, Russia for invading, and the Western powers for NATO’s eastward push. The United States and Britain, he recalls, reneged on their commitment at the start of the conflict in 2022. “This violation has rankled in the minds of the Ukrainian policymakers.”

Today, when the world’s once-mighty colonisers stand unable to ensure their own safety without America’s economic and military support, the Continent stands devastated by the worst conflict on its soil. The entire West is in turmoil, unable to find a solution to the continuing death and destruction of a people buffeted by global geopolitics gone awry.

As Europe’s problems become the world’s problems, to paraphrase what External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar has said, Devare makes a telling point that a majority of nations, hit economically if not more, to which the West, unless directly concerned, pays only lip service, are unwilling to take sides. In an increasingly transactional and exploitative world, they cannot identify with either Russian aggression or the values the Western world preaches to others.

The genesis of the Ukraine conflict lay in the Soviet Union’s disintegration and the Western ‘triumphalism’. One issue was nuclear non-proliferation. Ukraine unilaterally and voluntarily gave up its 1,700 nuclear warheads. Despite this largest nuclear non-proliferation step, no firm guarantees were given to Ukraine, either by the US or Russia.

Ukraine’s people, Devare feels, now wonder if Russia would have “dared to attack” had it remained a nuclear power. But these are ifs and buts of a history that is never fair and just.

He is fully supportive of India’s current diplomatic stance, buffeted as it is by the US and Europe, and supports a negotiated settlement. Of India’s purchasing Russian oil at concessional rates, which saved USD 30 billion, he avers and but for that: “India would have been in a very precarious situation.”

ALSO READ: The Ukraine Peace Plan, Europe’s Hubris

Whatever its outcome, the conflict’s resolution may leave many issues unresolved and could lead to future disputes. Even East-West geopolitical changes, on which he delivers no value judgments. For now, Devare says the conflict has led to the proximity of Russia and China, who now believe in “a once-in-a-hundred-years opportunity that they should take full advantage of.”

His most tricky assignment, for four years, was in Sikkim, the Kingdom before its merger. The Political Officer, as the office was called, outsmarted the Chogyal, who wanted to retain independence as the king. Increasingly alienated from the poor Sikkimese, he squandered money on organising fashion shows in the US. He was deeply influenced by Hope Cooke, his Gyalmo, the American-born queen. Her presence was a matter of concern when India was watching the Chinese posture on the Sikkim-Tibet border.

But before she left, for good, Devare recalls her barging into his home with Holloween festival revellers one late evening and, to the shock of Sikkimese staff, demanding that the two dance!

In the Indian Foreign Service (IFS), key neighbourhood assignments are essentially to Pakistan, Afghanistan and China. Instead, Devare’s career took him to the east, to Burma (Myanmar) and beyond, to Indonesia. This made him one of the key enforcers of India’s Look East Policy (LEP). He had the ears of Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao, the principal architect, and years later, of Jaswant Singh. It was “a kind of rediscovery” of ancient ties that has paid India and the region well.

The importance of the LEP, now the Act East Policy, can never be overestimated, whether in the 1990s or today. India is constantly seeking to be close to a region with cultural and economic links, away from a volatile West. The proverbial ice had to be broken with many of the ten countries, which were pronouncedly pro-West, looking suspiciously at India, which they felt was pro-Soviet. Among other diplomats, he aided Rao’s efforts, followed by Manmohan Singh, to join various multilateral institutions of ASEAN that India once ignored.

Without being preachy about what India could or should do, Devare records in some detail their past connections, Hindu and Buddhist, now Muslim in the case of Indonesia and Malaysia, which nurture deep multi-cultural moorings, as they evolve into modern nations, making rapid economic strides.

Devare has fond memories of the region, as he and his wife Hema, herself an accomplished scholar, delve into the cultural connections of fabrics and gods and goddesses.

Devare records that the advent of the conservative Wahhabi Islam in Muslim societies in the region has robbed them of some of the inclusivity that earlier existed when he witnessed them.

But he has a deeper lament about the ups and downs of democratic institutions he has witnessed in diverse societies: Burma (now Myanmar), Thailand and South Korea. The results have been diverse.

South Korea has prospered as an economic powerhouse and a regional player. But Burma, where the trend commenced in 1963, has seen more military than democratic functioning.

The military’s infusion into governance in many Asian societies may have brought some immediate relief, but it leads to long-term debilities. He laments this institutional aberration playing footsie.

Posted way back in 1980-82, more than 45 years later, Devare concludes the Burma chapter thus: “Living there and witnessing the situation was a disquieting experience. I sincerely believe that the people of Myanmar deserve a better future. My question is: Will that ever come to pass?”

He finds the world in “a poly-crisis” with “a sharp increase of violence everywhere”. India has to deal with the rise of China in the new millennium and attempts to redefine the global order.