India’s Last Liberal, Albeit Accidental, Prime Minister

Blessed with the world’s most complex neighbourhood, what would India have been like had it adhered to the “Gujral Doctrine”?

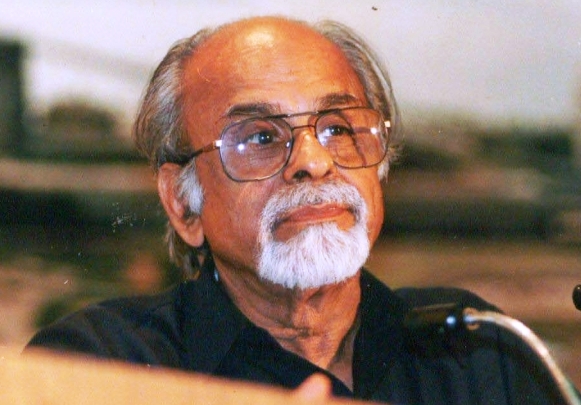

Inder Kumar Gujral, the 12th prime minister and author of the ‘doctrine’ – so named, not by him but by his trusted academic aide, Bhabani Sengupta – had unique perceptions about ties with neighbours. They angered the hawks who dominate the Sub-continental discourse.

Chances are that India would have had six friendly smaller neighbours and carried more weight among the world community as an Asian power. More likely, it would have been bullied by those who, after years of accusing India of playing the “big brother”, are now getting close to China, the ‘bigger’ brother.

Conclusion is difficult as two large adversarial entities, China and Pakistan that work in tandem on most issues, cannot be wished away. There was nothing formal or official about the doctrine, a set of five principles based on unilateral accommodation.

One, with smaller neighbours Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives and Sri Lanka, India does not ask for reciprocity but gives all that it can in good faith and trust. Two, no South Asian nation will allow its territory to be used against the interest of another country of the region. Three, no one will interfere in the internal affairs of another. Four, respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. And five, settle disputes through peaceful bilateral negotiations.

He believed that these five principles, scrupulously observed by all – repeat all – could recast the regional relationship, including the tormented India-Pakistan relationship, in a friendly, cooperative way.

Quintessential Nehruvian, Gujral was an idealist, but not a fool. He wrote in his autobiography: “The logic was that since we had to face two hostile neighbours in the north and the west, we had to be at “total peace” with other immediate neighbours in order to contain Pakistan’s and China’s influence in the region.” That has not happened. South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is almost defunct.

But Gujral believed that for India to become a global power in sync with its stature, it needs a peaceful neighbourhood.

Sometimes this actually meant offering the proverbial other cheek. The response to his ‘doctrine’ was not always reciprocated. But that did not deter him from engaging all neighbours – benign, indifferent, suspicious or hostile.

His political and personal lives, too, were tempered by this approach. His trademark Punjabi jhappi bypassed the conventional handshake, to the silent annoyance of the bureaucracy, but helped strike an instant rapport. Like millions, India’s 1947 Partition uprooted his family. But he bore no rancour. Pakistanis were among his best friends.

In my last interview with him, he shook his head with disapproval at India nursing any superpower ambitions. “It is more important that we live in peace.” He would have been a hundred this month. He died in 2012. He led India for all of 11 months (April 1997 to March 1998), but is remembered 22 years later, as the most affable and accessible prime minister.

A political lightweight, he was truly an “accidental prime minister” long before Manmohan Singh (2004-2014). Born pre-Partition, in present-day Pakistan, both shared close affinity. Without attaching his doctrinal label, the Singh Government reached out to neighbours with two huge grants to Bangladesh and made imports from all smaller neighbours duty-free.

With Musharraf’s Pakistan, too, cross-border intrusions stopped in Jammu and Kashmir. Discussed through backdoor talks, the Kashmir dispute could have been resolved but for Musharraf’s domestic debacles. Hawks on both sides have to this day dominated after the 2008 Mumbai terror attack.

Gujral was propelled into top post by the quirky uncertainties that govern coalition politics. Other contestants squabbled furiously and pulled each other down. He got it for two reasons: he was the least unacceptable among the contenders, and his good relations with the Nehru-Gandhi clan heading the Congress Party.

Yet, Congress pulled down his government, forced an election, only to lose it badly. As the PM, the sailing was not smooth. He had to cancel Sengupta’s appointment as adviser. His asking the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), the government’s external spy agency, to close down a unit dealing with Pakistan hurt intelligence gathering on militancy and terrorism, angering India’s strategic hawks.

As foreign minister, he earned a legion of critics when he hugged Saddam Hussein and visited Saddam-occupied Kuwait. His defence was his concern for the safety of millions of Indian workers in the Gulf region. For them his government organized the world’s largest peacetime airlift.

Along with then premier VP Singh, he ended the Indian Peace Keeping Force operations in Sri Lanka. Delhi lost the goodwill of both Colombo and the Lankan Tamils, but a bad legacy had to end. His 11-month premiership saw the Ganga water sharing pact with Bangladesh. The Left-leaning liberal resisted signing the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). That helped the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led government to conduct the May 1998 nuclear tests.

Member of Indira Gandhi’s “kitchen cabinet”, Gujral was information minister when she imposed Emergency in 1975, detaining opposition leaders and censoring the media. He quietly disagreed and was replaced. She sent him as envoy to Moscow. Besides growing a Lenin-like beard, he also consolidated Indo-Soviet ties. But he did not mince words while telling then Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko that Moscow had seriously erred in invading Afghanistan. From Moscow, he befriended physically and culturally-close Central Asia that he called India’s “extended neighbourhood”.

During his stint, India became a dialogue partner of ASEAN and a member of the Asean Regional Forum (ARF). He was media’s darling, ready with a thoughtful smile and a coherent answer to most tricky questions. He would candidly admit failures.

A democrat, he always sought to carry others along in that coalition era, displaying, in his own words, “the ability to accommodate, iron out differences and even bear insults.” Gujral and his ‘doctrine’ would not have survived the present times, what with critics being asked to “go to Pakistan” and terror-factor compelling India’s muscular approach.

Although he was an ‘opposition’ premier, the Manmohan Singh Government had accorded him a State funeral. The Modi Government, shunning anything remotely Nehruvian, has shunned any centenary commemoration.

He was India’s last of the liberals who made it to the top howsoever momentarily. Such people don’t make it in public life any more.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com