Kadam Kadam Badhaye Ja – Stepping Down Memory Lane

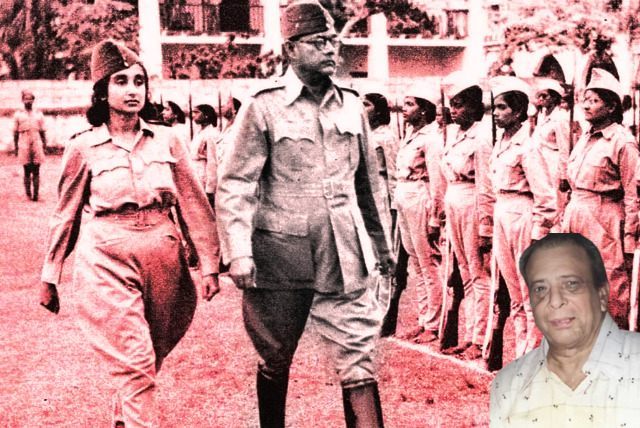

Of the Indian diaspora, none has memories of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, the last of the titans of the freedom movement, like the Indians in Singapore. Bose nurtured the Indian National Army (INA) to drive the British out. Although it failed, it paved the path to freedom.

Eight decades down, that memory remains fresh in the hearts and minds of those who witnessed it or their descendants. It is not surprising that the Tagore Society last month combined Singapore’s 60th founding with India’s 77th Republic Day.

The Society celebrated it with the launch of the book, Kadam Kadam – The Long March, which combines the most popular song of the Bose-led movement, Kadam Kadam Badhaye Ja, with the INA’s soul-stirring narrative.

It had the unmistakable touch of Indian cinema of yore, deeply influenced by Bose and the freedom movement. The book was originally written as a novel by Nabendu Ghosh, a renowned writer who scripted most of the Bimal Roy films.

There was also a contemporary touch. The novel was Ghosh’s last, and he had beckoned his daughter, Ratnottama Sengupta, to his deathbed and asked that she carry his legacy forward. A noted journalist and film curator, Ratnottama has fulfilled that mission with the launch, firmly linking Bollywood and the Bose legacy, and not just for the followers in Singapore.

The event and the book also lent another Bollywood touch by reviving memories of “Nazir Chacha” – actor-filmmaker Nazir Hussain, who did character roles in a hundred films during the 1950s-80s, including Parineeta, Do Bigha Zameen, and Devdas.

“Imagine my astonishment when Baba (Ghosh) declared that he must write about Nazir Chacha in INA,” Ratnottama says. Still a schoolgirl, she did not realise that her father had seen great potential in Hussain. He was the protagonist of the original novel Kadam Kadam.

“Empathise with my predicament when Baba handed me the last novel he had penned, entreating me to carry forward the torch of the freedom seekers who once were taken prisoners of war (POWs).”

A fireman with the Indian Railways, Nazir, had joined the British Indian Army that fought in Burma during World War II. When taken POW by the Japanese, like thousands of other Indian soldiers, he volunteered to join the INA.

The decision was not easy. The novel says: “Will you join the Indian National Army?” – the British soldiers taken POW by the Japanese were asked.

“Many agreed. Some were hesitant. ‘We don’t know who’ll command us. What sacrifices have they made for the country?’

“I also debated with myself. ‘Patriotism is commendable, but what’s the future of this Army?’ But Siraj joined the INA because he believed, ‘Those who fight for Freedom always sacrifice their own lives.’

‘Such love for the country!’ Nizam ridiculed Siraj. ‘How much opium have they fed you?’

‘You’re unaware of the intoxication I’ve tasted,’ Siraj smiled.”

Through Siraj, the novel describes Hussain’s transition from a soldier to a storyteller, staging plays as part of the INA’s propaganda campaign. Bose watched his play Balidaan and commended his effort and the message it sent to the Indian expatriates.

The most significant part of Nazir’s effort that gelled with Netaji was stressing Hindu-Muslim-Sikh unity. It ran through Bose’s years of fighting for freedom from outside India. And although INA’s effort failed, it culminated in the famous Red Fort trial of three of its officers – Prem Kumar Sehgal, Shah Nawaz Khan and G S Dhillon – a Hindu, a Muslim and a Sikh.

Sengupta says: “This is not only the story of a band of soldiers who were hirelings of the British Army. Nor is it about a war fought on the foreign shores of Malaya, Singapore and Burma. Kadam Kadam, for me, is part of my family lore. For I grew up in the tall shadows of the men who live behind the names, Sirajul and Shankar – the protagonists of “The Long March.”

Ghosh proved right in his judgment of Nazir Hussain. The first film directed by Bimal Roy, Pehla Aadmi, was hugely popular. Nazir had a role in many of Roy’s films. He met Dr Rajendra Prasad, India’s first President, and went on to make Ganga Maiya Tohe Piyari Chadhaibo, the first film in Bhojpuri, the language common to Prasad and Hussain. With its success, Hussain is called “father of Bhojpuri cinema.”

To return to Bose and his legacy in the present-day Singapore, Ambassador TCA Ragavan, who was India’s High Commissioner in the city-state,writes “I was constantly confronted by the somewhat unusual fact that so many Indians who had been living in Singapore for four or five, perhaps more, generations, preserved memories of their association with Netaji and the INA as part of their own distinctive Singaporean legacy.”

Singapore has the iconic Cathay Theatre, where Netaji had made his first public appearance in early July 1943 and where, later on 21 October 1943, he announced the formation of a Provisional Government of Free India.

Raghavan records being invited in February 2010 to attend a special screening at the Cathay Theatre in Singapore. “What made the evening unusual was that the film being screened was not a new release, but the occasion was nevertheless a special one. The then President of Singapore, S.R. Nathan (1924-1916) was the guest of honour, and the audience included those who had served in the Indian National Army (INA) or their descendants.” The screening was of Shyam Benegal’s 2004 film Bose-The Forgotten Hero.

Raghavan writes: “I recall finding many in the audience at the end of the film in tears. For them, Subhas Chandra Bose was not just a nationalist icon in distant India but a vital part of their own lives in Singapore.”

Raghavan says Bose’s legacy in Singapore “is not uncontested. The majority of Singaporeans – ethnic Chinese – suffered greatly during the Japanese occupation, and that is part of the island’s collective memory. So, memories of 1942-45 are divided.

“These memories inevitably form part of any discussion of Netaji and the INA in Singapore. Possibly, Singaporeans, both of Indians and Chinese origin, have wisely come to accept different readings and interpretations of the same history. If anything, their experience demonstrates that it is possible to live and even prosper with multiple, even conflicting, interpretations of history.”