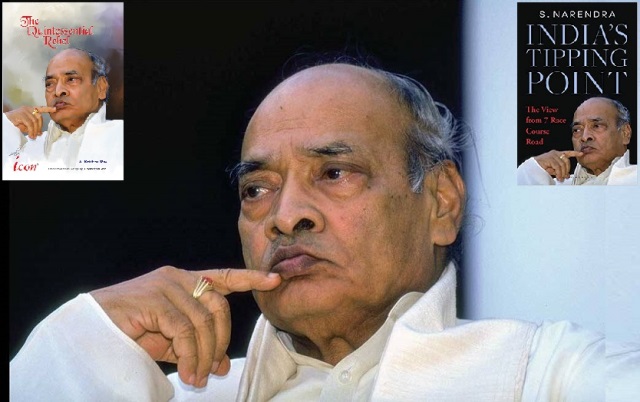

Narasimha Rao – A Rebel & A Reformer

Two books symbolize the sea change India witnessed as the last century ended and is still on. The author of one, S. Narendra, spent a better part of his communicator’s career articulating the government’s ‘socialist’ policies. Till the prime minister, his finance minister, and India itself, opted for economic reforms.

Four years after he stepped down as the prime minister, P V Narasimha Rao, who helmed the risky, resented-by-many change, lamented to A. Krishna Rao, the other author, that he had lost Andhra Pradesh’s chief ministership to advocating the Nehruvian model, and then, the prime ministership for pushing the reforms, though he did not regret either.

As one who provided the political sinews needed to enable finance minister Manmohan Singh to enforce the reforms, Rao was and remains, the man who opened the door. After Nehru who is demonized, albeit for reasons beyond his combining socialism with welfare, Rao, billed as the modern-day Chanakya, is India’s most written-about ex-premier today.

Four reasons have motivated analysts to dwell on him almost two decades after he died in 2004. All of them are relevant.

He died virtually shunned, even despised, by the Congress that he served. The party is under dire stress today battling Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led BJP juggernaut. It lacks political direction and ideological coherence. It can neither shed nor grow under the Nehru-Gandhis.

Rao, PV for short, helmed the government when the controversial Babri Masjid was demolished. Its rubble has continued to contaminate a pluralist India’s sinews, casting a dark shadow as it seeks its place on the global table.

Though not the first or the last time, financial scams coloured Rao’s five-year tenure (1991-96). Many more have surfaced since. Adani is the latest.

The present political dispensation has sought to appropriate Rao. Like Sardar Patel, put on the world’s tallest pedestal, not so much for his contribution to the nation, but because Congress ignored him. It’s a political me-too. In Rao’s case, the Bharatiya Janata Party wants to make inroads into the Telugu-speaking South.

The analysts’ fourth reason should actually be the first. For, Rao-launched economic reforms are why India and the world should recognise his legacy. They woke up the sleeping giant.

ALSO READ: The Prime Minister Whose Work Speaks Louder

Three decades on, reforms have been embraced by successive governments, not only of Manmohan Singh, Rao’s nuts-and-bolts man but also those of Nehruvian I K Gujral and BJP’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The Modi Government is building on that edifice, whether or not it admits it.

Narendra correctly titles his book using the Narasimha Rao years (1991-96) as India’s Tipping Point (Bloomsbury India). An ‘insider’, he was Rao’s media advisor, but insists, “not a confidante”. Rao pitted him, a civil servant, before his doubting political critics led by Arjun Singh, to justify the choice of an unshackled elephant as the reforms’ symbol.

“India is a large, polyglot, federal, parliamentary democracy. The decision-making process is slow but surefooted, the giant steps are impactful. Other countries already have tigers and lions. Moreover, the elephant is identified with Lord Ganesha”, Narendra succinctly explained. He got into many Congressmen’s crosshairs.

He insists that PV, no “reluctant reformer”, well understood the Indian ethos. India had lagged behind Southeast Asia’s ‘tiger’ economies by decades and an adversarial China by 12 years. Yet, the ‘elephant’, being stirred up for a tiger’s leap, unlike the others, needed to have “a human face.”

Both authors dwell on the Rao-Congress relationship in their separate ways. The first Congressman, not a Nehru-Gandhi, lacking their looks and charisma, Rao ran a minority government for a full term. One problem was that he was from the South. That the two authors are also from peninsular India helps shed that bias.

If Narendra’s approach is to-the-point, Krishna Rao, a senior journalist, portrays PV, as the title of his book suggests, The Quintessential Rebel (SR Publication). Yet another biographer, Vinay Sitapati, calls Narasimha Rao, as the name indicates, a “half-lion”. Rao’s critics may not appreciate these nuances. To them, these descriptions may not jell with the image of a sensitive, soft-spoken man. But they would agree with what Narendra calls Rao’s deep personality flaw of being indecisive and uncommunicative in the face of a crisis.

That fatal combination governed the immediate aftermath of Babri’s destruction. In hindsight though, one is left wondering how and why a seasoned politician like Rao believed in the BJP leadership and specific commitments made before the Supreme Court and then cried ‘betrayal’. It was a collective failure on which Rao presided and that, like Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, shall always remain his negative legacy.

Crises dogged Rao even after the loss of power and retirement. The last bit was thanks to his ungrateful party which “let the law take its course” when Rao was charged in a court, the first former premier thus hauled up, for allegedly paying lawmakers to save his government. This stance was missing when the Sonia-blessed Manmohan Singh Government was on a similar sticky wicket. Or now, when Rahul Gandhi is convicted, however controversially, for a poll-time verbal faux pas.

Heading a disparate coalition, Rao was a weak premier, weakened further by the ‘bushfires’ lit by fellow Congressmen. Many family loyalists were his ministers. The more ambitious ones succeeded in driving a wedge between Rao and Sonia and on her nod, launched a rival party that cut into Congress votes in 1996.

Rao lost and went home. But the party has also lost, despite wielding power for a decade (2004-2014) under another non-Gandhi, but Sonia nominee.

There is no denying Rao’s hesitancy in acting against ministers who came under the scanner in the Harshad Mehta scam, and later in dealing with the sugar import scam.

A fuller study of Rao, as the authors have attempted, must include steering the Indian ship in the post-Soviet world, amidst Dunkel and Kickleger pressures by the newly-emerged sole superpower. It must cover Kashmir, the Pandits’ exodus, and cross-border infiltration. It must analyze how the BJP and the Left united to thwart all his plans.

Related to reforms is another lasting legacy of Rao. The “Look East Policy”, now called “Act East Policy”, has provided India with an entire region next door and a much-needed platform that has evolved into Indo-Pacific.

Narasimha Rao was many things, but essentially, a poet. Krishna Rao, a poet himself, quotes PV’s August 15, 1947 poem:

“For ages, he had silently

Bearing injustice with a smile,

Now, he is seething with anger

With redness of dusk

Reflecting on his face;

He is a revolutionary sage!”

That was the common Indian man when he gained freedom at midnight.

The writer can be contacted at mahendraved07@gmail.com