The current set of democratically-elected leaders have little understanding of the deep contradictions of global order, or their own conflict-ridden societies

The circle is now complete. Major democracies — the ‘oldest’ (Britain), ‘greatest’ (the United States) and the ‘largest’ (India) – all have elected populist, aggressive government leaders. This sounds the death-knell to whatever is left of political liberalism.

They all want to make their respective nations ‘great’, which is fine. But they stand charged with using divisive methods at home and adopting protectionist and exclusivist measures abroad.

The ‘greatest’ is erecting walls, wooing North Korea while winking at Russia and China and threatening Iran, the bête noire in West Asia. The latest muse is Imran Khan who must keep the Afghan door ajar to facilitate an American flight faster than Vietnam.

The ‘largest’ is calculating a $5 trillion economy and become a ‘guru’ to the world. But on the ground, it protects its bovine population in a mix of death to those who kill or tan it, but profits for those who export it.

‘Outsiders’ and those not in sync with the majoritarian agenda are asked to leave. Someone ordained: “go to the moon” – and this is not inspired by Chandrayan 2, the moon mission.

As their number mounts, finding a common thread becomes difficult. But their varying agendas using race, religion, region, ethnicity, colour, besides trade and global concerns like the climate change, has become the new normal. It has pushed the world further to a restless and triumphant political right.

The democratic distinction that they give themselves but deny to others is blurred. Vladimir Putin recently said: “the liberal idea” had “outlived its purpose.” The growth of populist movements throwing up ‘nationalist’ leaders and political parties across the world suggests he is correct.

Long before Donald Trump, these movements brought to power Viktor Orban (Hungary), Erdogan (Turkey), Duterte (the Philippines) and Matteo Salvini (Italy); with populists sharing power in Poland, Austria, Slovenia, Finland and Estonia. In France and Germany populist parties are set to play an increasing role in coming years. Brazil’s Bolsanero is a latter day addition – and more are coming.

Xi Jinping and Abe Shinzo would fall in that category. So would Benyamin Netanyahu and a common friend of them all, Narendra Modi.

The latest is Boris Johnson. His aggressive Brexit advocacy is part of the same isolationism.

“I’ll make Britain great again’, Johnson says, distinctly echoing Trump. For a former journalist and editor of prestigious journals, he is being unoriginal. But then, he feels close to Trump and despite Trump’s past fusillades against him, they (add Imran, too) are now a mutual admiration society.

Johnson, a biographer of Winston Churchill, sees himself in that leader. But times and contexts change. As Economist says, like Churchill, Johnson has also inherited Britain’s worst crisis since World War II. Brexit, Britain’s self-goal, could do or undo him, with deep repercussions either way.

To be fair to Boris, strictly going by promises made last week, he has defied many things that Brexit crusade has been about. Many Britons have viewed it from racism and anti-immigration prisms. Brexit was about reductions in future. But Boris has said he will make legal half-a-million illegal or unregistered immigrants, introducing a number system with some compassion.

Boris, given his Turkish ancestry, perhaps, has done better than Trump who, although of German descent, wants ‘outsider’ to quit America. Sustaining Britain’s inclusive approach, he has a Pakistani Muslim to manage finance and a via-Africa Indian woman to pilot the immigration and counter-terrorism policies. Only time will tell how Britain holds out against the global illiberal avalanche.

There is hope, perhaps. As an Urdu expression goes, “umeed par duniya kaayam hai,” (hope sustains life). Post World War II, whatever be their political belief, people could aspire for a better future. That hope is sinking with the advent of this century.

Unwelcome, migrants are ghetto-ed and ill-treated, if not killed. No trade union rights. No dissent. Not even disagreement. Even elections, with varying degrees of democratic processes, are only hurtling people in one direction. Humans live by hope. But there is no utopia to live for.

Sadly, the current set of our leaders have little understanding of the deep contradictions of the global order, or their own conflict-ridden societies. They engage in politics of name-calling and sensationalism, Trump’s boast that he could kill 10m Afghans, but won’t, is a classic example.

If truth be told, this didn’t’ begin with Putin or Trump. From the 1980s onwards beginning with the Reagan-Thatcher combine, ruling classes all over the world presided over a period of psychological repression. A new normal was propagated through media, education and other means — that a world free of exploitation and injustice is impossibile. Inequalities are increasing, and are justified.

By the 1990s, younger generations had come to believe that There Is No Alternative (TINA). They were told that the idea that we share of collective interests is simply hogwash. It was explained in the name of individual liberty and advancement.

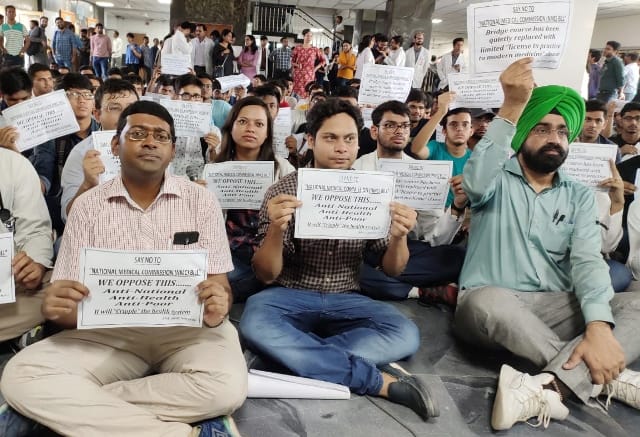

Liberalism is probably more challenged in India today than anywhere else because the country is the most diverse. Self-proclaimed custodians of caste and religion enjoying tacit political support are dictating people who they must meet, converse with, befriend and marry, what they should eat, wear, watch or read, whether or not they can use mobile phones, and even where they can go and when.

Aided by a corporate-owned media driven by profits and eyeballs, a public culture of hurt sentiment, violation of honour, with social and political license given to react to it in any brutal manner possible has been created. This climate of fear affects artists, intellectuals and even ordinary persons in public conversations.

Most founders of the Indian Republic (Nehru above all) aspired to create a liberal society. They did not foresee the extent to which it would, over time, evolve in a decidedly illiberal direction. Today, Nehru is a swear-word.

Here again, if truth be told, this did not begin yesterday. The political forces claiming to lead, and thriving on, a liberal ethos – the Congress, the communists, the socialists and the likes – themselves adopted illiberal courses and have now yielded space to those they fought. They are only whining today, unable to unite and fight back.

Mercifully, societies are not monoliths. Whenever and wherever a new draconian normal takes root, there are always forces who speak out for the oppressed. But as ordinary people increasingly become integrated into a digital political sphere in which melodrama rules, states and corporations will become more adept at manipulating ‘public opinion’. Already, those opposing it are being termed seditious.

Is it, then, the end of liberalism the world over? This is, like asking at the spiritual level: is it the end of Kalyug, the ultimate downfall?

Academic-journalist Pratap Bhanu Sharma says the end of liberalism is announced very frequently globally. “It’s almost like a recurring theme that there is a fundamental infirmity that makes it periodically vulnerable.”

This eludes a clear answer – if there is one.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com

]]>