One thing India needs most amidst the persisting Covid-19

pandemic, besides the still-elusive vaccine, and the equipment and health

infrastructure, which it has succeeded in producing, is the ubiquitous biscuit.

Making and marketing this humble ready-to-eat item

that is also most accessible and affordable, has posed as big a challenge as

fighting the pandemic itself. Both, urban India and the rural poor have over

the last three months virtually lived on it.

In initial weeks after the lockdown, one of the world’s

strictest, stores in richer neighborhoods of Mumbai, Delhi, and elsewhere, ran out

of it. For working-class citizens forced out of the cities for want of work, a

glucose-enriched biscuit was the most easily digestible antidote to hunger as

they headed home, miles away, many of them on foot.

Luckily, this sector – one of the very few – rose to

the challenge. Indeed, it is on a roll. Companies have worked overtime and registered

flourishing sales.

The big and small producers all experienced initial

setback in April. Production was hit by abrupt lock-down when workers either could

not report to work or had left for their villages. Yet, it was mainly the

biscuit that the migrant labour walking back home under extremely trying conditions,

found handy to carry, to feed self and the children.

As the world witnessed this heart-rending mass

movement, the worst since the 1947 Partition, there were also soothing pictures

of biscuit packets being tossed on to the moving trains and buses.

To feed these millions on the move, government

agencies, the NGOs, and buyers across the country rushed to get this packaged

staple. Biscuit thus fulfilled the original role for which it was conceived: nutritious,

easy-to-store, easy-to-carry, and long-lasting food for long journey.

For the pious, their conscience troubled by what was

happening around it is also the easiest and the cheapest give-away. The

smallest pack of five sells for as little as Rupees two. They prefer the little

biscuit packets over perishable sweets for distribution to the poor and the

children outside the shrines. Biscuit has become charity-favourite.

For the record, biscuit industry having Rs 12,000

crore annual turn-over is one of the largest food industries in India. It produces

5,000 tons daily. Biscuit is also a job-giver. The industry employs 3,50,000

directly and indirectly, over three million. Forty percent of the manufacture

is with the small and medium-scale factories. Growing at 15 per cent

pre-Covid-19, the industry as a whole has registered 50 percent higher

production during the lockdown.

However, the situation is iffy in that the factory

attendance is only around 66 percent, industry association says. This is mainly because

companies are currently running on limited staff. It’s still partial production

as there are not enough trucks to transport the product.

Covid-19 constraints may impact export and import too.

Globally, India is the third largest producer after the US and China. It is

also among the top five exporters. It imports biscuit as well to cater to the

elite consumer, a growing market what with more and more people emerging with

disposable incomes.

The per capita domestic consumption of 2.1 kilogram

is, however, low for a simple reason. Indians get a variety of staples,

affordable and available round the year. Biscuit goes with tea/coffee, not

food.

To clarify, the focus here is on the humble biscuit

with wheat flour, sugar and glucose and claimed nutrients and not on the exotic

variety that has nuts, butter, raisins, chocolates, colours and aromas added

artificially with use of intelligent technology.

There is a vast market for biscuit in India that is

growing in rural areas. Large population base which majorly comprises rural

population creates a huge demand for an affordable biscuit. Unsurprisingly, non-premium

biscuits dominate the market in the industry’s forecast period 2019-2025.

Premium biscuits were also projected to exhibit the

fastest growth rate what with increasing awareness among consumers, widening of

distribution channels coupled with advertising campaigns, high visibility and

accessibility of biscuits in retail outlets. However, Covid-19 may change the

producers’ priorities. So, wishing them luck, this is best left for happier

times.

Why this bonding over biscuit? Why is it so popular? To

be sure, it is one of the most universally consumed foods. Across India’s

complex and varied culinary landscape where food habits (remember the

vegetarian-non-vegetarian divide?) often determine social relationships,

biscuit is neutral. It is consumed by people of all class, caste, religion,

ethnicity, and income. Wealthier Indians dip them in milky tea/coffee and poorer

ones in spiced tea or just water.

Biscuit can be found at luxury hotels, in an urban

ghetto as well as in the make-shift wooden kiosks along the farms of rural

India. Wax paper packaging gives it long shelf-life and salty or sugary taste

is welcome to those engaged in physical labour.

Biscuit has long history in South Asia having evolved with the Muslim rule. Even today, old parts of Delhi, Hyderabad or Agra cities have the producer/hawker armed with an iron slab on coal-fire making sugary, ghee-rich ‘nankhatai’.

The art of confectioning thrived with Europeans’

arrival, be it British French, Portuguese or the Dutch colonizing different

parts of India. Modern-day biscuit first became popular among Muslims when the

British introduced it in Sylhet in the present-day Bangladesh. The Hindu elite

took a while to emulate. What was elite food once has now been embraced as

comfort food by the common man. Think of the sweeper who, having cleaned the

road outside, taking the first sip of tea with biscuit.

There are social contexts galore if you use Bollywood

down the decades as a yardstick. One of the most telling, perhaps, is Shubh

Mangal Savadhan (2017). The young protagonist subtly conveys to the eager

heroine of his erectile dysfunction (ED) problem. He dips a biscuit in tea and

lets it crumble. Enamoured of him still, the girl, confesses to her best

friend: “I will never be able to have biscuit and tea!”

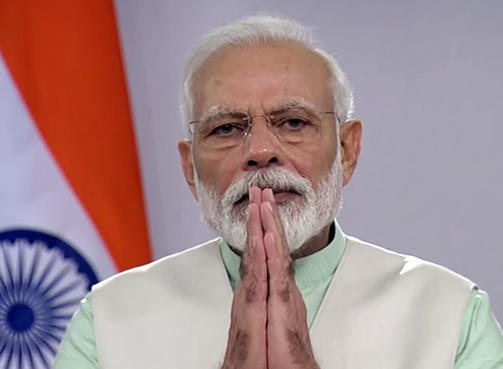

Over three months after Prime Minister Modi’s first announcement,

although the pandemic is not, India’s lockdown is beginning to ease. For

workers, the village-to-city reverse journey has begun. As they travel back, not

on foot this time and with hope in their hearts, biscuit is there on the trains,

at railway stations and awaiting them in factory canteens.

The

writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com