In a chilling revelation, an ABC journalist narrated his experience in China and how he and his family escaped after being intimidated by Chinese authorities.

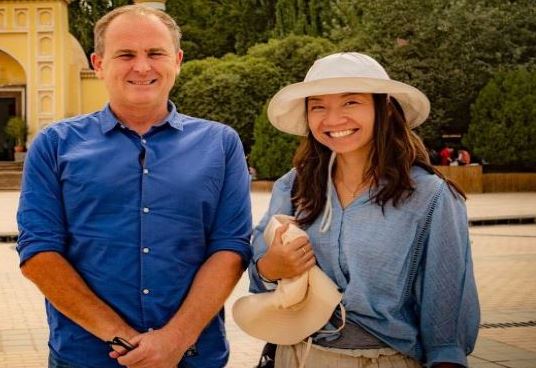

In an article for the ABC, Matthew Carney, who served as the ABC’s China bureau chief from 2016 to 2018, revealed how he received a telephone call from the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission in August 2018 and how that call marked the beginning of something else, “more than three months of intimidation until my family and I were effectively forced to leave China”.

The man from the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission told him that his reporting had “violated China’s laws and regulations, spread rumours and illegal, harmful information which endangered state security and damage national pride”.

“The fact is that every foreign journalist in China is under surveillance. But tracking my activities picked up significantly after that Friday night phone call,” he writes.

“There is the kind of surveillance the Chinese government wants you to know about. When I was reporting on the mass detentions of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, for example, the ABC team was surrounded by about 20 security officials, followed by midnight knocks on our hotel room doors and questioning about our daily activities,” he says.

Giving the grim and horrifying details of intimidation by the Chinese government, Carney said that he has seen the hidden cyber-surveillance.

“One night in the early hours of the morning, I woke to see someone remotely controlling my phone and accessing my email account. They searched and found an email from activists in New York that I was CC’d into requesting to have the famous ABC ‘tank man’ footage from the Tiananmen Square massacre given a UNESCO heritage listing,” he writes.

“The email was left open so I could see it, which I believe was a deliberate attempt to let me know they were watching,” he says.

Carney said that he did not share his story fearing the safety of ABC people working in China. But now he is sharing as Bill Birtles, the ABC’s correspondent based in Beijing, and Mike Smith, the AFR’s correspondent based in Shanghai, boarded a flight to Sydney after the pair were questioned separately by China’s Ministry of State Security.

Following the call, the journalist was threatened for months.

He said that one way the Chinese authorities try to force foreign journalists to self-censor their work is by threatening not to renew the 12-month residency visas. “I anticipated trouble, so submitted my renewal application six weeks before it was due to expire. If things were okay, you could expect approval in about 10 days. I did not get a response,” he writes.

Instead, he was ordered to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for “a cup of tea”, a phrase that every “foreign journalist knows is a euphemism for a dressing down”.

He was questioned during the call by the Chinese Foreign Ministry official.

“It was now a week before my visa was due to expire and with it the supporting visas for my wife and three children,” he says.

“We booked flights back to Sydney for the following Friday night. The plan was to shield the kids from the drama and if worst came to worst, pick them up from school and leave straight for the airport,” the journalist continues.

But one morning, he was told the visa had been approved. He and his wife went to the immigration police to have visa extensions stamped into our passports.

The official at the desk began entering details into the system, but suddenly the mood changed. Something was wrong. “We were told to immediately report to Public Security,” the journalist says.

“Once in the hands of Public Security, we entered into territory where interrogations and detentions are the norms. As I mulled the possibilities, fear sank into my gut. If this is where our investigation had ended up, then we were in serious trouble,” he adds.

In the coming days, they were interrogated and were told they will be put into detention.

After a round of calls to embassy staff, Chinese colleagues and the ABC, the journalist and his family decided the best approach was to confess guilt and apologise for the “visa crime”, with the condition that his daughter Yasmine stayed with them. She was mostly unaware of the severity of the situation.

“When the lead interrogator returned she told us she would consider our confessions, write a report on our case and send it to “the higher authority” for judgement. To heighten the tension once again, she said a result could take weeks. Our visas were running out in four days and by now we knew the consequences,” Carney writes.

However, another problem arises, a programme Carney made on China’s social credit system which uses digital technology to keep control of the population, was getting tens of millions of views around the world.

The Chinese woman that he featured in the story as a “model citizen” threatened legal action against me in the civil courts for defamation. “Her husband was an active and ambitious Communist Party member. Was this another way to intimidate me and the ABC?” he asks.

“I took advice from an American lawyer based in Beijing who urged me to leave China immediately. As soon as legal proceedings were lodged against me, an exit ban would be activated,” he says.

“But boarding the plane for a night flight back to Sydney with my family on a cold December night had never felt so good,” Carney notes. (ANI)