For all of China’s insistence that it is against “hegemony” – staring at the USA while it says it- Beijing sure likes to promote its own version of global security. It may couch its vision in glowing slogans, but a world made in China’s mold would be a frightening one.

At the World Economic Forum in January 2022, Chairman Xi Jinping reiterated his multipolar vision for “peaceful coexistence” and “win-win outcomes”, which necessitates abandoning a “Cold War mentality” and desisting from construction of “parallel systems”. Xi also criticized “exclusive small circles or blocs” that are responsible for polarizing the world.

Previously, Xi has called for “inclusive security” in the Asia-Pacific region, and Beijing regularly uses slogans such as “win-win cooperation” and “a community with a shared vision for mankind”.

Then, in his videoed keynote speech at the Boao Forum for Asia on 21 April, Xi announced China’s establishment of a Global Security Initiative to “promote security for all in the world”. Xi’s speech encompassed the principle of “indivisible security” to build “balanced, sustainable and effective” international security architecture.

The language of “indivisible security” is most notable, dating from the Helsinki Accords of 1975 during the Cold War. By using such language, China is simply parroting what Russian President Vladimir Putin argues, that the USA and Europe should not strengthen their “own security at the expense of the security of other countries”.

Of course, Putin is justifying his opposition to NATO’s presence in Eastern Europe, although ironically his own actions have caused further expansion of NATO.

Xi’s speech at the Boao Forum listed “six commitments”: (1) Adhere to the vision of “common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security and joint cooperation to advance world peace and security”; (2) Remain committed to mutual respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries, and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states; (3) Follow the UN Charter, reject the Cold War mentality and oppose confrontation between rival blocs; (4) Respect the legitimate security concerns of all nations, and uphold the principle of indivisible security; (5) Resolve differences through dialogue, oppose “long-arm jurisdiction” or unilateral sanctions; and (6) Insist on joint coordination to manage traditional and non-traditional security challenges (e.g. terrorism, cybersecurity and climate change).

Anyone familiar with Chinese policy will notice the recurrence of China’s favourite catchphrases in the above. Behind it is the narrative that China is a force for good, a champion of multilateralism and inclusive security, while the USA is a dangerous hegemon stuck in the Cold War.

This precisely echoes Putin’s argument, that his invasion of Ukraine was an inevitable and necessary reaction to NATO expansion. Beijing even orchestrated a nationwide education campaign to force this same narrative on China’s population. As Xi bolsters Russia and silently applauds Putin’s invasion, Beijing has increasingly referred to “indivisible security” in Europe and farther afield.

However, Xi’s “Global Security Initiative” is rather nebulous, and it will take time for the concept to catch hold around the world, if it does at all. Similarly, when Xi announced his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, it met with lukewarm reaction from outsiders because nobody really knew what it and its associated slogans meant. This is typical of Chinese foreign diplomacy efforts.

As John S. Van Oudenaren noted for The Jamestown Foundation, a US-based think-tank, “Rather than commit to formal bilateral or multilateral treaty alliances, China prefers to maintain a hierarchical network of strategic partnerships.” One example is the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Presumably, China will attempt to insert the Global Security Initiative as an added layer that brings a military dimension to existing transnational efforts.

Van Oudenaren summarized: “Under Xi, the PRC has abandoned this Dengist ‘hide and bide’ approach, and has sought to become a leading voice in all aspects of human affairs, including global security … Nevertheless, the current PRC leadership’s motivation to develop China into an international leader derives more from Xi’s embrace of strategic competition with the US than it does from any proactive vision for global affairs. In many ways, China’s advancement of alternatives to the prevailing international system amounts to a sophisticated effort to insulate the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) system from external geopolitical threats, the US above all, and to buy time to pursue Xi’s domestic vision of achieving national rejuvenation by mid-century.”

China insists the Global Security Initiative is not based on zero-sum geopolitics, but rather that it seeks “common security”. Closer to the truth is that Beijing wants to reduce American influence in international affairs, and to undermine the premise and capability of groupings like NATO, the Quad and AUKUS. Last year’s creation of the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) alliance accelerated Chinese rhetoric and criticism about “exclusive cliques”.

China has always been averse to NATO, and it especially fears the USA is trying to create an “Asian NATO”. Russia’s war with Ukraine has merely sharpened a split between China and NATO. In 2019, the EU had labeled China a “systemic rival”, and NATO has admonished China for its “lack of transparency, use of disinformation” and “coercive policies”.

Beijing has actively worked to insert a wedge between NATO and the USA. As alluded to, the main weakness of Chinese security ambitions is that it does not really have anything new to offer, because its main goal is simply to undermine American dominance.

China may enjoy success in economic plans such as the BRI, where it has attracted a range of different partners, but the Global Security Initiative would likely just attract a motley collection of like-minded authoritarian and anti-American partners.

By supporting Russia’s actions in Ukraine, Xi has exacerbated the “Cold War mentality” that it so vehemently rails against. Beijing is actively condoning another country to wage war, a blatant violation of all “six commitments” that smoothly rolled off Xi’s tongue at the Boao Forum. All should note that this is the kind of “indivisible security” that China imagines, where small countries must bow to the might of those who are bigger.

Van Oudenaren concluded: “The limited momentum that Beijing achieved in its half-hearted push to improve ties with Washington quickly dissipated in late February as Washington and Beijing staked out opposing positions on Ukraine. In the context of these already fraught relations, the Global Security Initiative’s framing and borrowing from the Kremlin’s foreign policy lexicon is likely to be interpreted in Washington as another signal that Beijing remains fundamentally oriented not toward cooperation, but strategic rivalry with America.”

All these warnings were evident when Chinese Defense Minister General Wei Fenghe held a telephone conversation with US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin on 20 April.

In a readout of that call, China’s canards were on full display, including that the USA should not aim to change China's system; must avoid alliances that target China; refuse to support “Taiwan independence”; and never seek a conflict with China.

Wei clearly signaled, “The US should not underestimate China’s determination and capability.” Taiwan remains a sensitive touchstone for China, with Wei warning, “If the Taiwan question is not handled properly, it will have a subversive effect on the China-US relations. The Chinese military will resolutely safeguard national sovereignty, security and territorial integrity.”

The end of the readout stated, “China urged the US to stop military provocations at sea and refrain from using the Ukraine issue to smear and sow false evidence against China, or threaten and put pressure on China.” This is perhaps an admission that China is – rightfully so – feeling pressure because of its blind support for Russia regarding Ukraine.

China’s recent signing of a security cooperation agreement with Solomon Islands is evidence that influence peddling and financial support can win friends, or at least buy support. That agreement, plus China’s dispatch of six police officers to the Pacific nation to train local police, is emblematic of China’s desire to spread its military and legal influence.

Unfortunately, as China has spread its BRI, criminality such as online fraud, gambling, human trafficking, animal parts trafficking (for traditional Chinese medicines) and money laundering often accompany it. Chinese organized crime gangs have exploited the BRI’s expansion – for example, masterminding telecom and cyber fraud from places like Cambodia, Myanmar and the Philippines.

China is extended a very long arm of the law. Its “crime fighting” enforcement actions have three strings to its bow: against crime in neighboring countries that might affect Chinese citizens living abroad or in China itself (e.g. armed patrols along the Mekong River alongside Laos, Myanmar and Thailand); the CCP’s Operation Fox Hunt to repatriate people wanted in China under the pretext of “corruption”; and pursuing political dissidents or opponents of the CCP.

From 2012-14, after Xi rose to power, an estimated 18,000 Chinese officials fled China, taking some USD125 billion with them. The State Supervisory Commission and Ministry of Public Security is in charge of tracking down former officials living abroad, and the odds are stacked against anyone netted in Xi’s campaign – the conviction rate is 99.9%, and only 30% of defendants receive lawyers. In 2015, Beijing had extradition treaties with 39 countries, but such a low figure means that China routinely uses “persuasion” (read coercion) to force people to return to China. This might involve threatening relatives in China or those living abroad; such tactics are also commonly used against Uyghurs from Xinjiang.

The expansion of China’s economic presence, and of Chinese expatriates, has resulted in a similar growth in extraterritorial judicial activities by Chinese authorities, even extending to the kidnapping of suspects. Alarmingly, China shows a willingness to be a world policeman.

As well as law enforcement, there is no doubt that China is attempting to expand its military presence around the world too.

This was first seen in the creation of a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base in Djibouti in 2017. This set a precedent, and other bases will surely follow as China seeks to station troops abroad. Indeed, the Pentagon’s 2021 report on China’s military stated that Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates, Kenya, Seychelles, Tanzania, Angola and Tajikistan are all potential locations where China is seeking facilities for either military or dual-use applications.

China routinely talks of “strategic strongpoints” that can “provide support for overseas military operations, or act as forward bases for deploying military forces overseas”. Such a model explicitly integrates commercial and strategic interests.

Despite Xi’s glib words of “peaceful coexistence”, the problem is that China is trying to impose its version of “a new type of international relations” on others, one that suits the CCP’s narrow-minded view of the world. This version of “security” promotes China’s take on international order, democracy, sovereignty, human rights and diplomacy.

As the world has seen, that includes mass human rights abuses in places like Xinjiang based simply on ethnicity and religion; the total suppression of political opposition in Hong Kong; economic and military coercion against other nations; and a creeping takeover of others’ territory.

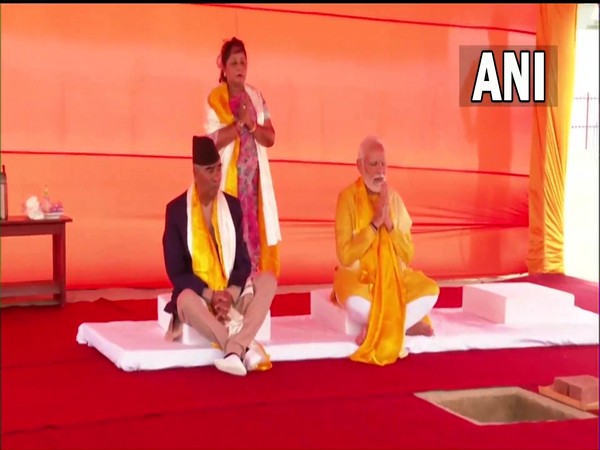

China is so busy pointing the finger at the USA, NATO, AUKUS and other alliances that it hopes nobody will notice it is pushing its own hegemonic plans to impose a peculiarly Chinese brand of authoritarianism on the world. (ANI)