Pakistan’s Defence Minister Khawaja Asif warned the Taliban regime on Wednesday issued a severe threat to the Afghan Taliban, warning that Pakistan could strike “deep into Afghanistan” and “push them back to the caves” if another militant attack occurs on Pakistani soil, Dawn reported.

The aggressive statement followed the collapse of peace talks in Turkey and a surge in border clashes. Four days of negotiations in Istanbul between Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban concluded without a resolution. The talks were mediated by Turkey and Qatar following deadly border clashes and a temporary ceasefire that began on October 19.

In a pre-dawn announcement, Pakistan’s Information Minister Attaullah Tarar said the latest round of talks between the two countries in Turkiye, which aimed to address cross-border terrorism emanating from Afghan soil, “failed to bring about any workable solution”.

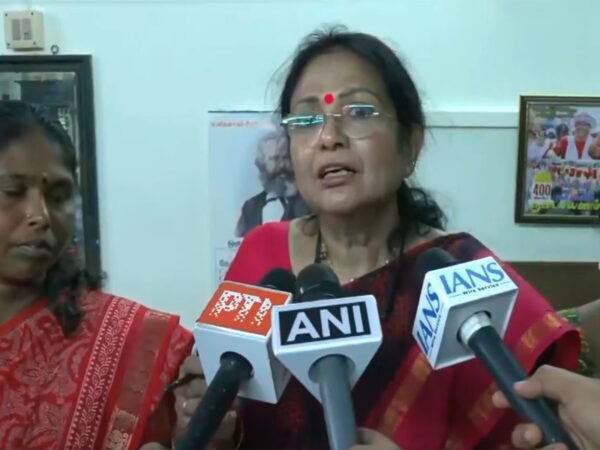

“We will conduct strikes, we definitely will,” Asif told reporters at Parliament House, when asked about the options available for Pakistan in case of cross-border conflict with Afghanistan, as per Dawn.

“If their territory is used and they violate our territory, then, if we need to go deep into Afghanistan to retaliate, we surely will,” he added.

The defence minister said that Pakistan had indulged in talks to give peace a chance on the request of brotherly countries, who the rulers in Kabul were persistently beseeching; however, “venomous statements by certain Afghan officials clearly reflect the devious and splintered mindset of the Taliban regime”.

“Let me assure them that Pakistan does not require employing even a fraction of its full arsenal to completely obliterate the Taliban regime and push them back to the caves for hiding. If they wish so, the repeat of the scenes of their rout at Tora Bora, with their tails between the legs, would surely be a spectacle to watch for the people of the region.”

The defence minister said Afghanistan neither “fulfils the definition of a state” nor was the interim administration so considered. “They are benefiting financially by being the rulers.”

Asked whether the Afghan Taliban were taking their country towards a similar situation as the United States’ military operation in Tora Bora in December 2001, Asif said, “It is definitely a possibility.”

Asif’s latest remarks come hours after he issued a strongly worded warning to the Taliban rulers in Kabul, telling them to test Islamabad’s resolve at their “own peril and doom” if they wished to do so.

“We have borne your treachery and mockery for too long, but no more. Any terrorist attack or any suicide bombing inside Pakistan shall give you the bitter taste of such misadventures. Be assured and test our resolve and capabilities, if you wish so, at your own peril and doom,” Asif posted on social media platform X, as per Dawn.

In a separate development, the United Nations voiced concern over the collapse of talks between Pakistan and Afghanistan, hoping that the “fighting will not renew”.

UN spokesperson Stephane Dujarric was asked about the collapse of the negotiations and whether it was a concern for the UN.

Pakistan and Afghanistan saw a worsening of ties in recent days, which featured border skirmishes, counter-statements, and allegations, as per Dawn.

The hostilities began earlier this month when an attack was launched on Pakistan from Afghanistan on the night of October 11. The attack had followed an allegation from the Taliban of airstrikes by Pakistan into Afghanistan — an accusation which Islamabad has neither confirmed nor denied. (ANI)