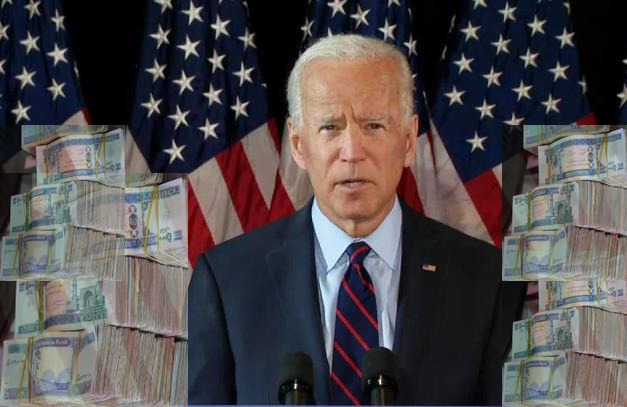

US President Joe Biden last week signed an executive order, splitting $7 billion Afghan funds deposited with the Federal Reserve. Afghanistan will now only get $3.5 billion as part of the humanitarian aid while the remaining $3.5 billion will be given to 9/11 victim families in the US.

Afghanistan has about $9 billion in assets overseas, including the $7 billion in the United States. The rest is mostly in Germany, the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland banks. International funding was stopped and Afghan money was frozen after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan last August. The Taliban expectedly have expressed anger over United States’ move and have sought to unfreeze all funds.

Taliban spokesman Mohammad Naeem said on Twitter that the theft and seizure of money held or frozen by the United States of the Afghan people represents the lowest level of human and moral decay of a country and a nation.

On Saturday last, the Afghan central bank — known as Da Afghanistan Bank — demanded in a statement that the Biden administration reverse its decision.

The move has also elicited angry responses from the Afghan public; there have been a series of angry demonstrations in Kabul, with common Afghani seething in anger over the US move.

Expert’s criticism

The decision has also drawn criticism from human rights groups, lawyers and financial experts who have warned that the move could gut the country’s central bank for years to come, crippling its ability to establish monetary policy and manage the country’s balance of payments.

Experts also said that the $3.5 billion set aside for humanitarian assistance would do little good unless the United States lifted restrictions on the Afghan banking system that have obstructed the flow of aid into the country.

John Sifton, the Asia advocacy director at Human Rights Watch, said in a statement that the decision would create a problematic precedent for commandeering sovereign wealth and do little to address underlying factors driving Afghanistan’s massive humanitarian crisis.

Torek Farhadi, a financial adviser to Afghanistan’s former US-backed government, questioned the UN managing Afghan Central Bank reserves. He said those funds are not meant for humanitarian aid but “to back up the country’s currency, help in monetary policy and manage the country’s balance of payment.” He also questioned the legality of Biden’s order and said that these reserves belong to the people of Afghanistan, not the Taliban … Biden’s decision is one-sided and does not match with international law, no other country on Earth makes such confiscation decisions about another country’s reserves.

ALSO READ: China Looks For A Toehold In Afghanistan

Some analysts also took to Twitter to question Biden’s order. Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Programme at the US-based Wilson Centre, criticised the scheme to divert funds from Afghanistan in a tweet.

Pakistan has also condemned the decision. Pak Foreign Office spokesperson Asim Iftikhar has called for the complete unfreezing of Afghanistan’s assets.

As reported by GeoTV, he said it is imperative for the international community to quickly act to address the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe in Afghanistan and to help revive the Afghan economy, as the two are inextricably linked. And the utilisation of Afghan funds should be the sovereign decision of Afghanistan.

The Debt

The Taliban, after taking control of Afghanistan had immediately claimed a right to the money. But what complicates the matter further is that a group of relatives of victims of the September 11 attacks, one of several groups who had demanded compensation for those killed in 9/11, have sought to seize this money to pay off their debt.

This debt is based on a default judgement titled ‘Havish vs Laden’ of 2011, awarding $6bn to a group of 9/11 victim families, as per a federal judge in New York. The parties named in the case —the Taliban, Hezbollah, Al Qaeda and Iran — never showed up (hence a default judgement). In its defence the Biden administration claims that this will open doors for expediting humanitarian aid to Afghan people, who are facing a lot of hardships.

The American media has lauded the decision, with Washington Post commenting in an article that though the issues, moral and legal, are extremely complex, with the ultimate disposition of the money up to a federal court in New York, the administration is surely right about one thing: Despite the desperate needs of the Afghan people, many of whom are at risk of starvation, it would be a mistake to put the money back at the disposal of Afghanistan’s central bank, with no strings attached — as the Taliban demands.

Pakistan’s Dawn in its editorial has commented that President Biden’s decision is simply appalling and lacks moral ground. It says further that for one, these assets belong to Afghanistan and not to the Taliban rulers. How can Washington justify inflicting collective punishment on the Afghans to penalise the Taliban? It raises a legal question as well. The money belongs to the Afghan central bank and therefore, should not be commandeered to pay the Taliban’s judgement debt. None of the 19 hijackers involved in the horrific terrorist attacks on that tragic day were Afghans. True, the plotters used Afghan soil and were under the Taliban’s protection, but to penalise the entire population implies that the attack had the sanction of the entire nation.

The decision compels one to compare this action to the colonial mind-set or colonial thievery of the past. The absurdity is that the richest country in human history is maltreating one of the poorest, for compensating the victims of and redressing a crime committed 20 years, in which the Afghan people had no role.

Further the Biden decision also gives birth to another quagmire, if it’s ready to transfer money to the Taliban administration, than doesn’t it means that it is tacitly recognising the Taliban government, leading other countries to engage with Taliban without its formal recognition?

(Asad Mirza is a political commentator based in New Delhi. He writes on issues related to Muslims, education, geopolitics and interfaith)