Two decades after it was released (on June 15, 2001) to critical and popular acclaim at home, screened at film festivals abroad, and lost in the final lap after being nominated for the Oscars, one reads several messages from Lagaan. Its memorable prayer ditty, “O paalanhaare”, with punch-line “tumrey bin hamraa kaun-o nahin”, areport in The Hindu newspaper says, comforts millions battling the Covid-19. Perhaps melodramatic, yet one may argue, for or against, why it reflects the prevailing mood of helplessness.

The second message is unstated. The song’s writer Javed Akhtar, composer A R Rahman and its producer and lead actor Aamir Khan contribute to cinema, upholding its role as the country’s most inclusive medium. It is important in the currently polarized socio-political environment. Their high visibility and successes, like those of many others, are testimonies of their larger social and cultural acceptance that ignores the present-day attacks on individuals and institutions.

The third message is about the Indian cinema itself. It has gone global. Lagaan is among those films that have given India and its entertainment sector largest-ever profile. This has also encouraged more film-making, as reflected in the pre-Covid figures taken from Google – 2,448 films were made in 2019 in different languages, earning $2.7 billion.

But the world’s largest cinematography continues to produce few quality films. After Mother India (1957) and Salaam Bombay! (1988) and since Lagaan reached the Oscar nomination stage at the 74th Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, no Indian film has qualified.

Lagaan’s fourth message is on the age-old song-and-dance sequences unique to Indian cinema. Earlier entries to foreign festivals were stripped of songs and dances to reduce length and reach the message directly to appeal to the Western sensibilities that determine the Oscars. Lagaan entered with most, if not all, songs that were integral to the narrative, well-composed and well executed. The Indian film-makers need not be squeamish about them, provided they keep the quality and mingle them into the narrative.

But Lagaan is much more than an Oscar-loser. This turn-of-the-century film is the last serious look at rural India. Save Shyam Benegal’s two films, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008) and Well Done Abbba (2009), and Peepli Live (2010) that was India’s official entry for the 83rd Academy Awards but did not win nomination, India’s countryside is absent in cinema. Lagaan is the last hurrah for rural India as the country urbanizes at a fast, haphazard pace.

Indicative of growing knowledge, too, Lagaan became a serious case-study for man-management lessons at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Indore. Fifteen seats and a full semester were reserved for it, but the IIM had to expand the time and seats when applications exceeded 300.

Indeed, Lagaan is also political material to study the Indian society. Relevant in the 19th and the 20th centuries, but equally now is the character of Kachra, the Maha Dalit (socially most oppressed) on whom much of the caste politics is played today. That also makes Bhuvan, the protagonist, obviously an upper caste farmer, a real hero. He stakes the villagers’ success on his inclusion in the cricket team. Today’s Bhuvans, sadly, are only slogan-mongers, even as Kachras, conscious of their strength, rise, intermittently, hesitantly, in a reservations-driven India.

Lagaan is mini-India. A classic from Bollywood’s cinema factory, it is in the same class as Do Bigha Zameen (1953), Mother India and Do Ankhen Barah Haath (both made in 1957) and Guide (1965), says film analyst Gautam Kaul. The only international example of a similar nature, he says, is MGM’s Gone With the Wind (1939) that, after every two decades, gets a world premiere!

Aamir Khan is rightly acclaimed as producer and the lead actor, Lagaan was the brainchild of writer-director Ashutosh Gowarikar. His filmography of ten shows that this was no flash-in-the-pan. Swades (2004) and Jodha Akbar (2008) were outstanding, with strong messages delivered well. Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey (2010), a well-intentioned message film met with modest success. But of late, both audiences and critics have panned Mohen Jo Daro (2016) and Panipat (2019). It is difficult to repeat Lagaan’s success, like it happened, for example, to those who worked on Gandhi. With his penchant for and ability to deliver message, however, Gowarikar may have more to deliver.

He must get full credit for conjuring up this David-versus-Goliath theme set in British-ruled India on the lives of people in a village dependent upon seasonal rains for their survival. They live on territory of a kindly but hapless prince overruled by a cranky and arrogant British captain. The Briton challenges the villagers to, of all things, a cricket match, baiting them with waiving of land tax (lagaan) for three years if they defeated his team. Having no choice, a gritty youth forms a rag-tag team of total novices, and actually scores a narrow victory. This may sound crazy on paper, but Gowarikar made it believable.

In a glowing review, Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic late Roger Ebert likened Lagaan’s landscapes to those in Dr Zhivago (1965) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and compared Gowarikar with David Lean.

It featured a record 15 foreign actors, not just caricatures, some playing key supporting roles. This required engaging a separate casting director. British actors Rachel Shelley and Paul Blackthorne learnt their dialogues by heart (no dubbing) and braved the desert’s dry winter and summer. The entire crew, including the Britons, contributed handsomely to the relief rushed to the locals when the villages they had frequented were destroyed by an earthquake six months later. That was their tribute to ten thousand villagers who had played willing actors in the crowd scenes.

I have problems with the film being located in an imaginary Champaner in present-day Madhya Pradesh when there is one, very famous, in Gujarat. Agreed that real Champaner’s terrain did not suite the narrative. So, for authenticity, it opted for Gujarat’s Kutch district, creating a village set near Bhuj. The other issue is the mix of Awadhi, Braja Bhasha and Bhojpuri that are dialects of Hindi spoken hundreds of kilometre away in present-day Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. If these were to be the medium, the film could also have been located in northern India for greater authenticity. Obviously, terrain took precedence over the tongue.

Lots of cinematic licences. Audiences would have ignored them but for Amitabh Bachchan’s commentary at the film’s opening locating Champaner in Madhya Pradesh. But Aamir-Ashutosh couldn’t escape from Gujarat where, like Rajasthan, the terrain offers huge climatic and scenic variations needed for the film.

Interestingly, Lagaan had much in common with Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) besides Bachchan’s commentaries. The lead characters are named Bhuvan and Gauri. That film, too, was shot in Gujarat. Four decades after she played the lead in Bhuvan Shome, Suhasini Mulay played Bhuvan’s mother in Lagaan.

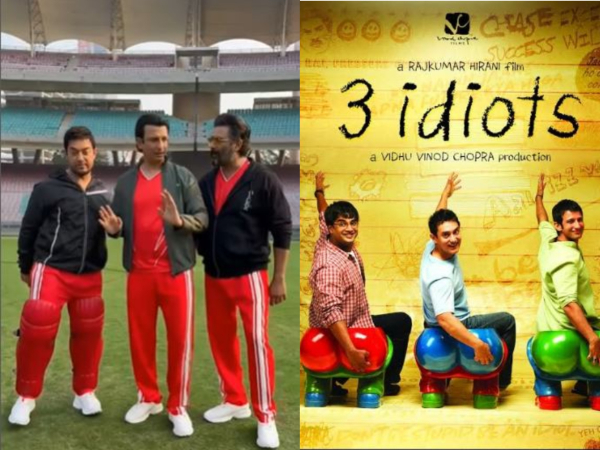

The film must be recorded for cricket used as the driving force to depict competition and a civilizational clash with patriotic touches. There were doubts about the ‘sporty’ angle. That part was planned as a surprise element in the film’s promotion, ostensibly so as make the theme look credible to the non-cricketing world. Lagaan was the first Indian film to premiere in China. Aamir Khan has since been most successful in that country with his PK, Tarey Zameen Par, Secret Superstar and Dangal, each setting viewership records. Like Raj Kapoor in the last century, Aamir is seen as an actor-director of substance. Globally, he enjoys as much following, if not more, as Shah Rukh Khan and Salman Khan.

Like cricket, rain plays a key role in Lagaan’s theme. During its filming, it did not rain at all in the region. However, a week after the shoot finished, it rained – like it did after Bhuvan and his men won the match. That brings the “reel life” and real life closer.

Cricket is a metaphor for modern India. But as Lagaan shows, rain is the permanent one, determining our lives, be it for two decades or two centuries or more.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com