What is common between Nadin Gordimer and philosopher economist Amartya Sen, the first the winner of Nobel for a highly rich body of fiction based on apartheid abuses and repression in South Africa, more violently so following accession to power of Africanner nationalists and the second for his path-breaking contributions to welfare economics? The answer lies in the question itself. Both Gardimer and Sen delved deep into murderous violence and injustices that have riven society across the world based on divisions of people on grounds of race, religion and class.

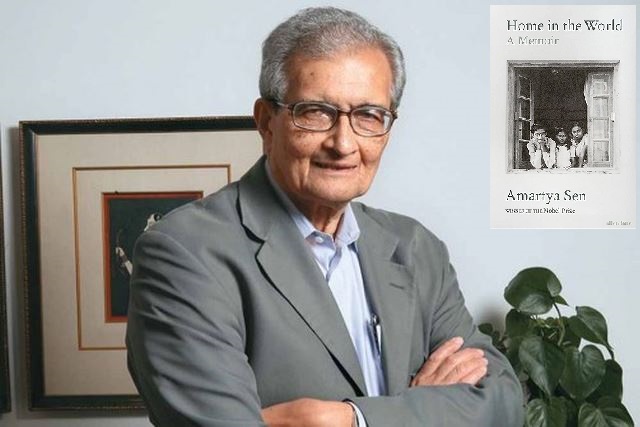

Gordimer died at the age of 90 in July 2004, three years after receiving the Nobel. Sen’s memoir Home in the World (till 1963 coinciding with his return to India after years in England and the US for study and subsequently teaching) was first published in 2021 to rave reviews in the world Press and otherwise universal acclamations. Publisher Allen Lane, part of the Penguin Random House group, appropriately decided to use what Gordimer said in the past about the philosopher economist in the dust jacket of Home in the World. She wrote: “With his masterly prose, ease of erudition and ironic humour, Sen is one of the few great world intellectuals on whom we may rely to make sense out of our existential confusion.”

Who will believe unless Sen himself would make the admission in the memoir how much he preferred mastering Sanskrit and Bengali at the cost of the language of the Raj when he attended school first at St Gregory’s and then at Santiniketan (abode of peace in English) where Rabindranath Tagore in 1901 set up an academic entity called Visva Bharati. Sen was at the Santiniketan school for ten years from 1941 to 1951 following which he joined Presidency College in Calcutta.

Sen writes: “My great loves at Santiniketan were mathematics and Sanskrit. In the last two years at the school, I specialised in science… It is not rare to be fascinated by mathematics, but being a fan of Sanskrit at school was more unusual. I was very absorbed in the intricacies of that language, and for many years Sanskrit was close to being my second language after Bengali, partly because my progress in English was very slow. At St Gregory’s in Dhaka I had resisted education in general, but English in particular, and when I moved to Santiniketan the medium of instruction was very firmly Bengali. The language of the Raj somehow passed me by – at least for many years.” Whatever that was decades ago, Sen is now hailed as the English-speaking world’s pre-eminent public intellectual for his oeuvre besides economics on social sciences and philosophy, his quality of prose, historical sense and a strong sense of equity.

In many cases what shape life will take depends on the influence of parents and grandparents. Take Nadine. Her mother Isidore Gordimer aghast at racial discrimination and indescribable economic exploitation of the black community by the South African apartheid regime ran a crèche for the black children. While this activism of Isidore invited the wrath of the government in the form of police raiding the family home and seizing papers and diaries, such experiences in her adolescence made of Nadine an anti-apartheid activist. Her political activism went to the extent of helping Nelson Mandela prepare his celebrated speech ‘I am prepared to die.’ The government came down hard on her by banning her books. But Nadine was not the kind to cave in to pressure.

Home in the World tells us the kind of profound impact the great Sanskrit scholar Kshiti Mohan Sen had on his grandson Amartya when the latter joined the ‘school without walls’ at Santiniketan. Kshiti Mohan’s lifelong passion was to explore India’s wealth of folk literature and also the long history of interactions between Hindu and Muslim traditions. Amartya writes: “Kshiti Mohan’s understanding that… Hinduism had been significantly enriched by the influence of Muslim culture and thought… found a strong expression in his English book on Hinduism.” This heterodox thesis challenges the sectarian thoughts of a large number of Hindu theorists. There were days when Amartya would be up at 4 a.m. like his grandfather and the two would go out for a long walk. As Amartya recalls the walks turned out to be great learning for him with the grandfather making him aware of subjects unknown. The walks also gave the grandson “the wonderful opportunity to bombard” Kshiti Mohan with questions on a wide range of subjects.

Sen writes: “A walk could become a class on subjects as the dismal way India treated its pre-agricultural tribal population, usurping their land (he knew well the sad history of that process, including the failure of successive governments to build schools and hospitals for them). He told me that Ashoka, a great Buddhist emperor who ruled over much of India in the third century BC, expressed special concern about ‘forest people’ in the already urbanising India, asserting that the tribal folk had their rights too, just like those who lived in the cities and towns.”

ALSO READ: Celebrating The Writing Inc

To tell the truth, many centuries later even today despite all the progress, adivasis continue to come in for unthinkable exploitation in the 21st century with their forest land being taken away by hook or by crook to house industries and many promises of their rehabilitation remain mostly unfulfilled. Incidentally, Rabindranath Tagore, who after repeated pleadings got Kshiti Mohan to join him “in the building of a new kind of educational institution,” at Santiniketan would have the Sanskrit scholar as partner in the very early morning walk.

But why Tagore was in “great need of an ally” like Kshiti Mohan. The poet wrote this about the scholar: “Even though he is well versed in the scriptures and classical religion writings, his priorities are entirely liberal. He claims that he gets this liberality from reading of scriptures themselves. He may be able to influence even those who want to use their narrow reading of the scriptures to reduce – and insult – Hinduism. At least, he would be able to remove narrowness from the minds of our students.” There were interesting exchanges between the two on religion.

When at 12, the grandson told Kshiti Mohan that he was not finding interest in religion, the grandfather said: “There is no case for having religious convictions until you are able to think seriously for yourself – it will come to you in a natural way over time.” Religion, however, never came to Amartya to which the Sanskrit scholar replied: “I was not mistaken. You have addressed the religious question, and you have placed yourself, I can see in the atheistic – the Lokayata – part of the Hindu spectrum.” Religious convictions may have bypassed him, but what, among many other pursuits of Kshiti Mohan, particularly stayed with Amartya is his grandfather’s “involvement in the oral poetry of Kabir, Dadu and the Bauls.”In this pursuit, Kshiti Mohan was moved by two considerations – first, India’s wealth of folk literature must be put on right pedestal, being often neglected by our “elitist bias.” Second, the pursuit was part of his deep engagement with the “long history of interactions between Hindu and Muslim traditions in India.”

Why did Amartya name his son Kabir, though this is a Muslim name? One is his respect for the “ideas of the historical Kabir” and then his Jewish wife Eva Colorni liked the name. Eva told Amartya: “It is just right that the son of a Hindu-origin father and a Jewish-origin mother should have nice Muslim name.” How beautiful life would be if the world lives by this secular spirit. Sadly, this is today largely missing in India. Armed with a spirit of questioning and engaging in argument acquired under the tutelage of a benign grandfather, Amartya arrived in the big city Calcutta in 1951 to study at Presidency College, which presented many exciting intellectual challenges. But Amartya was like “challenge rather than accept at face value the ideas and knowledge we were being offered, and sometimes questioned what we were getting from the books and well-respected articles.” Didn’t his economics professor Tapas Majumdar say “don’t dismiss the possibility that the received argument, despite common belief, is simply incorrect”?

As Amartya says in his student days Karl Marx’s intellectual standing outshone everyone else’s. Even then, Marxian economics didn’t feature much in classes at Presidency or any other colleges. At a personal level, Amartya found “in the corpus of Marx’s writings… concepts that seemed to me to be important and nicely discussable.” Moreover, he found “arguing about Marx was fun.”

This still is. He found the distinction that Marx made “between the principle of ‘non-exploitation’ (through payment according to work, in line with the accounting established by his version of the labour theory of value) and the ‘needs principle’ (arranging for payments according to people’s needs, rather than their work and productivity) was a powerful lesson in radical thought.” At the same time, Amartya finds Marx’s “scrutiny of political organisation… oddly rudimentary. It is hard to think of a more breathless bit of theorising than the idea of ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’, with underspecified characterisation of what the proletariat’s demands are (or should be), and very little by way of how the actual political arrangements under such a dictatorship might work.”

Read More:https://lokmarg.com/