A sensitive mind can be a curse. Especially, when there is hatred and bloodbath all around us. The sensitive mind empathises, it responds, it gets hurt. It feels choked. Violently choked. As if a monster is sitting on its body-chest and strangling the windpipe with both hands. Helpless under the brute force, the mind nearly surrenders as life peters out of the lungs. Nearly.

A sensitive mind can be redeeming. Even in the dystopian surroundings, it notices the young girl hiding behind a wall, holding a toy in hand, and smiling gently. A smile that brings some fresh air. The mind breathes a lungful, rises phoenix-like, and smiles back.

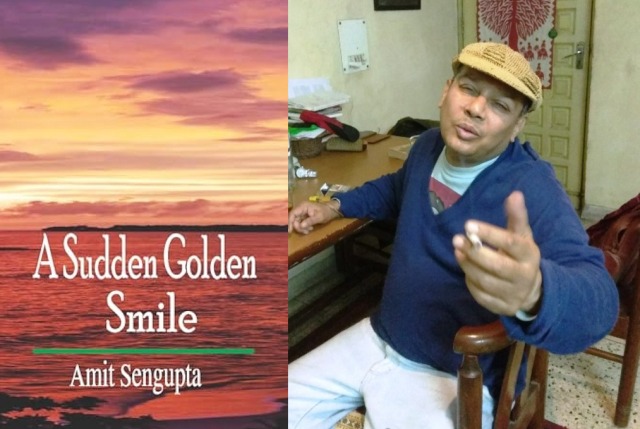

A Sudden Golden Smile.

This title by Amit Sengupta, a journalist, an activist, a teacher, a lover and more, brings together years of his sensitive outpouring, dipped often in frustration over injustices that target the vulnerable. It is also an account of discovering oneself, finding inner peace in conflict zones, looking for an antidote to all that has gone wrong with the world. It discovers hope in the most mundane: in early sun-rays falling on a sleepy village, the flutter of a bird’s wings and in a stranger’s smile.

Do you hear the continuous rattle of a creaky desktop in a rented, sunny 2BHK? Amit is furiously pounding on an outdated keyboard, belting out lyrical protest anthems, recreating his daily ordeals, spitting a mouthful every now and then, drawing strength from a half-burnt cigarette dangling from his lips. He straightens his back after completing his rant, smiling.

As I flip through his book, many lives, some known and others anonymous, come alive with their known and anonymous stories. Vinesh Phogat, a five-feet-five-inch wrestler cast in steel, cries her heart out from the pages. Iranian girls wave Mahsa Amini’s posters and scream for their rights. The indigenous people deep in the forests of Madhya Pradesh are guarding their land, their mother. A broken father from Gaza, with a dead child in hand, looks at the Merciful in the sky for courage. God, if there is one, is silent.

But even amid the most inconsolable tragedies and loss, the human spirit, like the author who has penned these stories, remains unbroken. It finds moments of joy and happiness in the hour of wolves, however temporary.

My mind sleepwalks into a scene from The Bicycle Thieves, the 1948 B&W classic by Vittorio de Sica. One hour into the movie, the protagonist Antonio Ricci, exhausted by the search for his stolen vehicle, decides “why kill ourselves worrying” and feels that Bruno, his accompanying son, deserves a treat. Counting the few bills in his wallet, he takes Bruno to a restaurant beyond his means where live music is played. “Let’s forget everything and get drunk”. When the son, in an apparent attempt to imitate a stylish girl sitting at another table, tries clumsily at the fork & knife, Ricci tells him, “Eat, eat. Don’t worry.”

This book, in spite of the impending doom, carries the same indomitable message. Don’t worry, seize the moment.

Yes, the book is smouldering with deep angst. But it offers more than just the anguish. There are journeys and explorations. Amit covers and uncovers everything that surrounds us, and yet unreachable to many of us – from sports track to the village paths, from a sleepy platform in the dead of night to the squeaky charpoy in a mountain village, from a theatre filled with Bollywood melodies to a forest which throbs with adivasi songs. The reader could be left regretting why one missed such simple joys that life provided free of cost. How could one man live so much in the same years of existence that we, for me as one, spent complaining about monthly EMIs, noisy air-cooler and corrupt politicians!

Amit moves much too fast than his readers can catch up. He jumps from Bimal Roy to Manmohan Desai, Dudhwa tribals to Sonagachi sex workers, from Kafka to Sahir… you keep adding. This string of essays and hard-hitting words, some written in a stream of consciousness others packed with powerful commentary, tell you about things that were always at your arm’s length but you never reached out.

Some pages are damp with tears, others fuming with disgust, even melancholy, and some bathed in love. You need not be an Albert Camus, Che Guevara or John Berger reader to live these moments of longing and belonging. You only need a sensitive mind. One that empathises, one that responds, one that gets hurt.

After reading the book I went to sleep fully content. Life is good, I told myself, from the first clang of the rail to the last clang of the rail, with a little help from a lusty puff at a half-burnt cigarette.