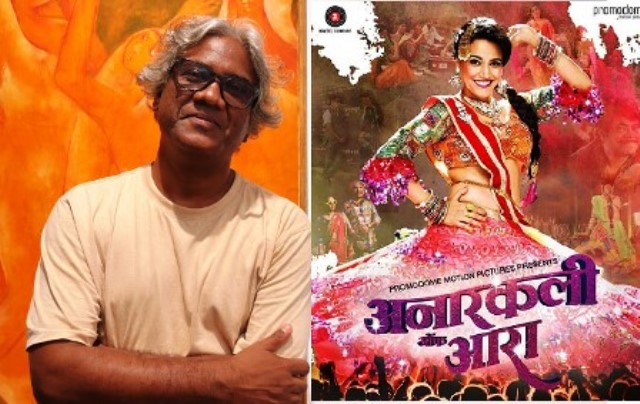

Avinash Das, director of several acclaimed movies, says communal narratives in Bollywood existed earlier too but now they are incentivised, patronised. His views:

Renowned music composer AR Rahman has been in news for his comments on changing power structure and a ‘communal bias’ in Bollywood. In my opinion, his statement needs to be read less as an individual opinion and more as a symptom of a larger cultural anxiety. When someone of Rahman’s stature speaks cautiously or ambiguously, it is not necessarily an ideological confusion; it is a reflection of the narrowing space available to public figures today.

In highly polarised environments, silence is not neutrality. It is often enforced.

What we are witnessing in contemporary times is not just the fear of backlash, but the fear of being algorithmically punished, economically isolated, or culturally erased. The market, the state, and a certain dominant section of public sentiment now work in tandem. This convergence leaves very little room for moral clarity.

As a filmmaker, I see this as a dangerous pattern and phenomenon. Authentic art thrives on dissent and discomfort. When even the most respected artists begin to self-censor, it signals a deeper structural problem — not an individual failure of courage.

The idea that Bollywood was always fully secular is itself a comforting myth. It was plural, yes. But pluralism is not the same as secularism. What has changed today is not ideology alone, but the power structure that governs storytelling.

Earlier, communal narratives existed at the margins. Today, they are incentivised. Patronised.

Films that simplify history into moral binaries are rewarded with visibility, protection, and amplification. Indeed, this is not simply a case of organic cultural expression. It is the relentless process of wilfully ‘manufacturing consent’ through cinema.

When storytelling starts aligning more with power than the lived reality, communalisation becomes inevitable. The danger is not that Bollywood is becoming communal. The danger is that it is being trained to see communal narratives as safe, profitable, and “nationalist”.

Yes, the industry is loaded, but not in a crude or conspiratorial way. It is loaded structurally.

Meaningful cinema requires time, risk, and ambiguity. The current ecosystem discourages all three. Financing is tied to optics. Distribution is tied to political mood. Exhibition is tied to outrageous economics.

Films like The Kerala Story succeed not because of ideology, but because they fit perfectly into a system that rewards provocation and polarisation, over creative and critical inquiry. Meanwhile, filmmakers who once made layered, aesthetic and morally complex films, are pushed into silence or compromise. Not because they lack ideas, but because the cost of honesty has become unsustainably high.

This is how censorship (invisible or otherwise) works in modern democracies. You don’t ban films. You make certain kinds of films impossible to make.

So what is the best way for the film industry in the future?

Surely, the future of the industry does not lie in appeasement or neutrality. Both are illusions. It lies in decentralisation.

Bombay cinema needs to unlearn its dependence on validation from power, whether political or corporate. Smaller budgets, independent distribution, regional collaborations, and direct audience engagement are not romantic ideals anymore. They are survival strategies.

Most importantly, filmmakers need to reclaim ethical clarity. Not slogans, not propaganda, but intellectual honesty. Cinema does not need to shout. It needs to insist. On complexity. On contradictions. On human truth.

If the industry forgets this idea of realism, it will continue to exist, but it will end up becoming futile. Finally, it will simply not matter.

(The narrator began his career as a journalist, working in both print and television, and transitioned into the world of cinema. His directorial works include Anaarkali of Aarah, Runaway Lugaai, Raat Baaki Hai and In Galiyon Mein among others)

As told to Amit Sengupta