What can one write about Ashok Kumar, who died 22 years ago, at age 90, and whose last film was in the last century? A lot, actually, if the present film fraternity eyeing the future is looking for a case study from the past. It may find some answers, though not all.

His legacy needs a re-look when the country’s cinema is facing multiple crises. For one, institutional challenges to the studio and the star systems. Ashok Kumar straddled both. His Bombay Talkies, a major studio, lasted till the studio system itself had to yield place to the star system. Kumar was among the early beneficiaries of the change.

Now the star system is threatened. Today’s frequently-failing stars can’t sustain the country’s 12,000 cinema theatres. Jubilee times – silver, golden et al – are past. They are forced to take recourse to the OTT (over-the-top) platforms proliferating with their own global cinema, breaking geographical barriers. Alongside, films are being financed by a new set of foreign-financed studios that dictate terms to individual filmmakers. Film-making has become increasingly money and technology-driven.

Two, on his success, Ashok Kumar invited Bimal Roy to Bombay. Along with the 1947 Partition, this triggered the influx of many more and not just from Bengal. This evolved into what is Bollywood today.

That Mumbai-based network producing Hindi films faces challenges from some of the regional language films. Bollywood must meet it by reaching out to those cinemas. But more importantly, by injecting a measure of discipline into its money-washed work culture. Collaboration in the making and marketing of RRR (2022) indicates some action on the first. On the latter, one can only hope that Bollywood is resilient enough to apply correctives — without awaiting lessons from some retired colonel that Ashok Kumar portrayed in Chhoti Si Baat (1976)!

Three, discipline was one reason behind Kumar’s success, of being sought after by three generations of filmmakers. He came to work on time, left on time and spent evenings, besides being with his family, rehearsing his next day’s dialogues. If Amitabh Bachchan is busy at 80 today, and his contemporaries and some younger lot are not, it is because of his punctuality and work ethic.

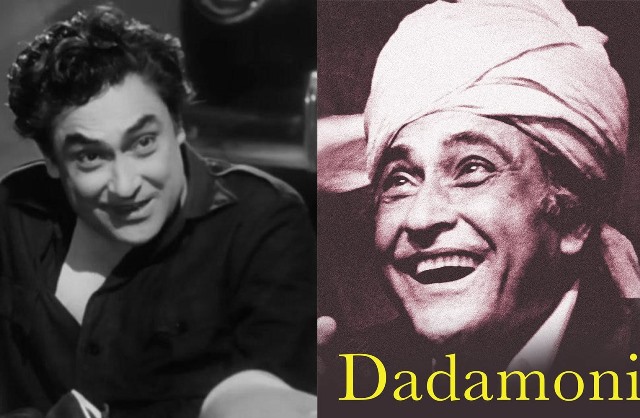

It would be impossible, even disastrous in the present times, to follow Ashok Kumar’s stipulation that he would not embrace the heroine. His smiling eyes did the romancing. He was called ‘dadamoni’, the affectionate elder brother, by everyone, including his legion of heroines. There were no scandals around Ashok Kumar, his biography by Nabendu Ghosh, who wrote many of the Bimal Roy classics, tells you.

ALSO READ: Ameen Sayani – Music To The Ears

Ghosh wrote Dadamoni: The Life and Times of Ashok Kumar when the thespian was around. It has got a new life with a Foreword by Kumar’s eldest daughter, Bharti Jaffrey, and an Afterword by Ratnottama Sengupta, Ghosh’s journalist-curator daughter. Together, the two ladies bring Ashok Kumar alive with innumerable insights and anecdotes.

The quintessential family man kept the promise he gave to Himanshu Rai, the man who launched his reluctant acting career, to stay away from ‘flappers’. Such a story would be boring today for those who devour filmy gossip and social media that get juicy bits, often from the stars themselves.

Dadamoni’s is not a rags-to-riches story. His well-heeled family did not mind his working as a laboratory technician in a film studio but was enraged at his becoming an actor. His engagement broke. He was pushed into an arranged marriage that lasted a lifetime. Society then enjoyed watching the film stars but treated them as social outcasts.

Shedding Ganguly, his surname, set the trend for ‘Kumars’: Uttam, Rajendra, Raaj, Manoj, Sanjeev, even Dilip (Yusuf Khan). Indian cinema’s first male superstar, he launched or promoted many, including Dilip, Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand — the troika that ruled the Hindi screen for decades. In his later years, he did supporting roles with them.

A sucker for good author-based films, he promoted writers like Sadat Hasan Manto, Ismat Chugtai and Shaheed Latif. He produced Parineeta based on Sharat Chandra Chattopadhyaya’s novel. It helped that he became a partner of Bombay Talkies and then the owner. He also launched his own production house. An astute businessman, he owned prime property around Kala Ghoda in South Bombay and nursed Rhythm House, the city’s iconic music hub.

Biographer Ghosh, also a fan, finds nothing negative about his idol. But Kumar’s younger daughter Priti recounts his smashing the Chinaware when in a foul temper, which was rare. She ended one on a hilarious note. She pleaded that he was about to smash an expensive crystal. He angrily demanded a cheaper one. She obliged. Dadamoni’s temper came crashing down instead.

Films had begun to ‘talk’ by the time he began but had yet to sing. Kumar sang with Devika Rani in Jeevan Naiya (1936). Pre-playback, Ghosh recounts, the composer and his team, perched on a tree branch to record Dadamoni and Devika singing, came crashing down. But Ashok Kumar did not give up singing. He was India’s first rapper with his “rail gaadi” in Ashirwad (1968).

With his smooth, natural style, he was the first to free acting and dialogue delivery from theatrics. No swagger. Less of speaking; he felt that was ‘preaching.’

Though beholden to the beauteous Devika Rani, he boycotted her years later. She had refused to meet Jawaharlal Nehru, the future prime minister. He called her ‘vain’ and ‘too proud’ of her beauty, film writer Gautam Kaul records. The boycott persisted till she met Nehru.

The variety of roles Dadamoni played, even their opposites, would be the envy of any actor, anywhere, anytime. The British rulers loved him as a cop but threatened to arrest him when he portrayed a rogue cop. Given his popularity, they reasoned, the public would get the wrong message.

He was a judge – also one accused of murder in Kanoon (1960). He played the thief in Jewel Thief (1967) because the Anand brothers – Dev and Vijay – were confident that given his image, none would suspect him of being one. He showed a flair for comedy, teaming up with Pran 27 times. Soap opera Hum Log was the flavour of the 1980s, the golden era of the government-controlled Doordarshan. Audiences waited to see how an episode they loved would end with Ashok Kumar’s message.

Despite hits from the word go, his stardom was not easy. A Brahmin romancing a Dalit, Achhut Kanya, a great social message, did not please the conservative. His song in Kismet (1943) ‘Door Hato Aye Duniawalo Hindustan Hamara Hai’ drew British censors’ wrath during the war years. The song was against the Germans and the Japanese, not the British. This worked. He stood for democratic values. When Hitler, on seeing Achhut Kanya sent a congratulatory telegram, he tore it off.

He admired Hollywood, but he refused an invitation from the legendary David Lean. He did not want to be typecast in bit roles. “I am an Indian and have no ambition to conquer the world,” he wrote back to Lean.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com

Read More:https://lokmarg.com/