Illegal migration has been a persistent issue in Assam, a state in the northeastern part of India, for decades. This phenomenon, particularly from neighbouring Bangladesh, has significantly affected Assam’s demographic, social, political, and economic landscape. The National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) are two controversial measures aimed at addressing this issue. However, their implementation has sparked intense debates, both within Assam and across India. This article delves into the impact of illegal migration in Assam and argues why prioritizing the implementation of the NRC and CAA is essential to resolve long-standing tensions in the region.

The Genesis of Migration in Assam: The problem of illegal migration into Assam can be traced back to the colonial era, particularly during British rule when the need for labor in tea plantations and agricultural work drew people from Bengal, including present-day Bangladesh. Following India’s partition in 1947, the migration issue persisted due to the porous border shared with East Pakistan and later Bangladesh. However, the real surge in migration happened after the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, when millions of refugees fled to India, many of whom settled in Assam. Although most returned after the war, a substantial number remained, sparking demographic changes that have had lasting effects on Assam’s society and politics.

Demographic Shift: One of the most significant impacts of illegal migration in Assam has been the demographic shift. Over the years, the influx of migrants from Bangladesh has led to a substantial increase in the state’s Muslim population, particularly in border districts. According to various reports, districts like Dhubri, Goalpara, Karimganj and Barpeta have seen a considerable rise in Muslim populations. This demographic transformation has caused anxiety among the indigenous Assamese population, who fear becoming minorities in their land. The changing demographic has had ripple effects, including in the domains of cultural identity, political representation, and access to resources.

Economic Strain: The influx of illegal migrants has placed a strain on Assam’s economy. Migrants, particularly those from rural and impoverished backgrounds, have added pressure to the state’s already limited resources. Jobs, especially in the informal sector, have become scarce for locals, with migrants often willing to work for lower wages, thus displacing native Assamese laborers. The illegal migration has also put pressure on land, with reports of land encroachments by migrants causing further unrest. Agriculture, the backbone of Assam’s economy, has seen disruptions as illegal settlers often occupy agricultural lands, leading to conflicts with indigenous farmers.

Cultural and Linguistic Erosion: The Assamese people take pride in their rich cultural and linguistic heritage. However, with the influx of a large number of migrants, the Assamese language and culture have faced the threat of marginalization. Assamese nationalism, which is deeply intertwined with the state’s cultural identity, has been overshadowed by the changing demographic patterns. Many fear that the continued migration will lead to the erosion of Assamese traditions, customs, and linguistic dominance in the state. This cultural alienation has been a key factor behind the rise of various ethnic and nationalist movements in Assam over the years.

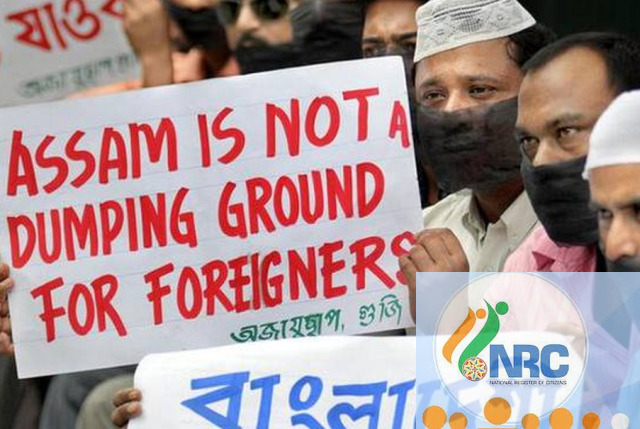

Political Instability and Communal Tensions: Illegal migration has fuelled political instability and contributed to communal tensions in Assam. Various political parties have used the issue as a tool to consolidate vote banks, often exacerbating divisions along religious and ethnic lines. The politics of appeasement have led to a polarized society, with one section supporting the protection of illegal migrants for political gains while another demands their identification and deportation. Communal violence, such as the Nellie massacre of 1983, where over 2,000 people were killed during anti-migrant protests, highlights how deeply entrenched the migration issue is in the state’s psyche.

Security Concerns: Assam shares a long and porous border with Bangladesh, which has facilitated illegal migration over the years. The security implications of this are profound. Apart from economic and cultural issues, there is a growing concern about the infiltration of anti-national elements, including militants, through these porous borders. The Assam insurgency and the rise of extremist groups in the region have been linked, in part, to illegal migration, as militants have reportedly exploited the migrant issue to recruit and operate within the state.

The NRC and CAA Debate: To address the issue of illegal migration, the Government of India has proposed two major policy measures: the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Each of these measures aims to identify and regularize citizenship status, but their execution has been fraught with controversy.

The NRC is a mechanism that seeks to identify and document all legal citizens of Assam. It was initially implemented in Assam following the Assam Accord of 1985. It was signed after years of anti-immigrant protests by the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and other Assamese nationalist groups. The accord set March 24, 1971, as the cut-off date for determining Indian citizenship in Assam—those who arrived before this date would be considered citizens, while those who came after would be regarded as illegal migrants.

The updated NRC was published in 2019, and it excluded nearly 1.9 million people, raising concerns about its accuracy. Critics argued that many legitimate citizens were left out due to bureaucratic errors and insufficient documentation, while others claimed the process targeted specific religious communities. Despite these challenges, proponents argue that the NRC is crucial for identifying illegal migrants and ensuring that Assam’s indigenous population is not displaced or marginalized.

The CAA, passed in 2019, seeks to provide citizenship to non-Muslim refugees from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan who arrived in India before December 31, 2014. The act primarily benefits Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians who fled religious persecution in these neighboring countries. However, the exclusion of Muslims from this list has sparked accusations of religious discrimination and a violation of India’s secular constitution.

In Assam, the CAA has been particularly controversial. While the act aims to protect religious minorities, many Assamese people fear that it will legalize the stay of Hindu migrants from Bangladesh, further exacerbating the demographic imbalance in the state. Assamese nationalist groups argue that the CAA undermines the NRC and dilutes the Assam Accord, which sought to protect the state from illegal immigration regardless of religious affiliation.

Despite the controversies, prioritizing the implementation of the NRC and CAA is crucial for several reasons:

Restoring Demographic Balance: The NRC, if implemented properly, can help restore Assam’s demographic balance by identifying illegal migrants and addressing the concerns of the indigenous population. It would prevent further demographic shifts and ensure that the state’s resources, including jobs, education, and land, are primarily available to legal citizens.

Assam’s rich cultural and linguistic heritage is at risk due to illegal migration. A properly executed NRC would help protect the state’s unique identity by ensuring that the Assamese people do not become a minority in their homeland. Additionally, the CAA, despite its controversies, could play a role in protecting persecuted minorities while maintaining the region’s delicate social fabric.

Security Concerns: Prioritizing the implementation of both the NRC and CAA can address security concerns by identifying non-citizens and reducing the risk of extremist elements using Assam as a base for their activities. A clearer identification of citizens and non-citizens would also facilitate more effective border management and reduce illegal crossings.

A well-executed NRC would reduce the politicization of illegal migration and provide a clearer framework for addressing the issue. Political parties would no longer be able to exploit the issue for electoral gains, leading to more stable governance in the state. Furthermore, by legalizing persecuted minorities through the CAA, the government could create a more stable and harmonious society.

Illegal migration in Assam is a complex issue with far-reaching consequences on the state’s demographic, economic, cultural, and political landscape. While the NRC and CAA are controversial, their proper and prioritized implementation can help address many of the challenges posed by illegal migration. For Assam’s indigenous population, the stakes are high, and any solution must balance the need for demographic protection, cultural preservation, and humanitarian considerations. By implementing these measures judiciously, the government can work toward ensuring long-term stability and peace in Assam.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/