Promita, a journalist based in Mumbai with roots in Bengal, says a movie needs to be judged by the audience and not the State. Her views:

I believe the issue around The Bengal Files should be seen in a straightforward way. If the film is propaganda, people will recognise it. If it has merit, they will respond to it. Either way, it should be the audience—not the government—that decides.

When the West Bengal government blocks the film on grounds of possible disharmony, it ends up repeating the same mistake it once criticised in others. Parties speak of freedom of expression when in opposition, but often forget it when in power. Many who once raised their voice against censorship are now silent. Freedom cannot be applied selectively.

I also connect this to my own past in Kolkata. During my graduation Part 1 and Part 2 exams at Victoria College in Rajabazar, I often noticed that some of the windows in the building remained shut. At the time, I didn’t know why. More than a decade later, when social media opened up access to forgotten accounts, I learned the truth. Those windows were part of a building that had witnessed violence and bloodshed during Partition, when a section of the city wanted Calcutta as its pound of flesh.

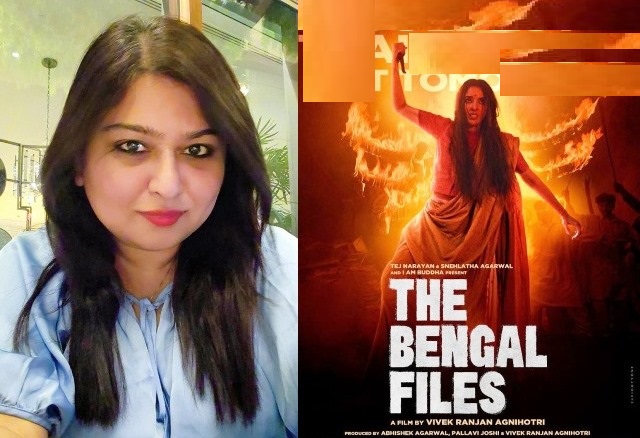

That discovery helped me understand why a film like The Bengal Files, directed by Vivek Agnihotri, matters. It is not just about cinema, but about bringing forward parts of history that were hidden. Eyewitness accounts had long been dismissed as exaggerations, all to maintain a carefully guarded version of secularism.

This does not mean the film is beyond question. It should be critiqued, analysed, and debated. But that can only happen if people are allowed to watch it in the first place. Suppressing it only closes the discussion before it begins.

As a journalist, I say it should be this way: trust the audience. Let them decide whether to accept, reject, or criticise a film. That is how democracy is meant to function.

As told to Deepti Sharma