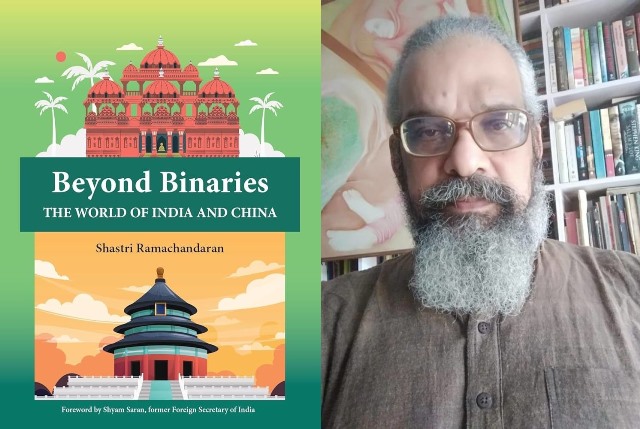

In his book Beyond Binaries: The World of India and China Shastri Ramachandaran quotes a Chinese proverb: “Men trip not on mountains, they trip on molehills.” In the fraught relations between the two neighbours, many molehills are becoming mountains, higher than the Himalayas.

There is no clear answer as to why two ancient civilisations that coexisted peacefully for over two millennia have been adversaries since the last century with no signs of a thaw. The “power partnership” and the “Asian Century” vision that the world’s two most populous nations proclaimed in 2008 when Manmohan Singh met Wen Jiabao, stands jeopardised.

In relatively better times, the two had played down the long-standing border dispute and sometimes cooperated in international forums. It is rare now. India has placed the border dispute and recurring clashes and intrusions at the centre of its relationship.

In the last decade, India’s political leadership that has blamed, with some justification, Prime Minister Nehru for leading the country to the 1962 conflict have not allowed a fair debate on the thaw in relations in subsequent years under Indira, Rajiv, Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh. Nobody even mentions why and how Modi’s hug-diplomacy failed and his well-meant hosting and being hosted by Xi Jinping, ended up in violent clashes at Galwan.

Shastri writes that while India has been unable to forget its territory loss and military debacle of 1962, he found it rarely mentioned during his seven years’ stay in China. “India and Indians need to face up to the fact that we are not in China’s sights as much as we think,” he writes. But while China couldn’t care less or can pretend to do so, now that it is miles ahead of India in economic prowess, a democratic India faces the odium from within and from its Western allies.

While these equations constrain overall economic ties, bilateral trade is booming, ironically, in China’s favour, and is likely to get stronger. China’s share in India’s imports jumped from $70.3 billion in 2018-19 to $101 billion in 2023-24, making it the top source country for goods and services. Ramachandaran provides the sober context to appreciate how China will continue to play a significant role in India’s present and future.

But the two are now decidedly in opposite geopolitical camps since India is viewed as a ‘pivot’ against China in Asia. In retaliation, never a respecter of India’s natural and historical role in South Asia, China has made Pakistan its bulwark against India, befriending “an enemy’s enemy.” It uses its deep pockets to make forays in the region bilaterally and through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While Bhutan remains under pressure after the Doklam episode, Sri Lanka, Nepal and the Maldives have seen political orders changing as per who is pro-India and who, pro-China. Overall, Beijing challenges India’s centuries-old cultural ties with people across South, Central and Southeast Asia.

ALSO READ: A Weakened Russia, A Resurgent China

Seeking to move beyond the black-and-white accounts that dominate the discourse on the Galwan clashes, Ramachandaran makes several interesting observations about the factors that may have contributed to China’s military provocation. It could be India’s deepening ties with the US, its role in the Quad, opposition to the BRI or its ambitions for supremacy in Asia; or all of these. “More than any or all of these, China’s provocative military attack could well have been to establish deterrence against India. This is a possible, and plausible, reason,” he argues.

On the other hand, India’s rising profile in the Indo-Pacific, including its strident calls for observance of maritime laws in the disputed South China Seas, has undoubtedly rankled the Chinese leadership.

India’s festering anger, fuelled further by China’s rapid strides across the globe, has bucked its ‘nationalist’ discourse that promises to get increasingly strident. Jeopardised, again, Shastri laments, are people-to-people contacts. These trends have exacerbated and led to the “manufacturing of mindsets”. Defying “an openly hostile” Indian media, and a part of the academia, Ramachandaran seeks to provide a counter-view that is cautiously optimistic, awaiting like many, for things to change. Some journalists have contributed to China and Sino-Indian studies, besides scholars, historians, generals and diplomats. But Ramachandaran is unique in that he has worked, on the ground, in both countries.

His collection of writings was executed between 2009 and 2016. As a good scribe, he ensures their relevance by drawing parallels. For one, he writes about how Modi launched his flagship Digital India programme on July 1, 2015, only a few weeks after visiting China’s hi-tech zone in Xi’an. He also writes extensively about how cooperation with China has played a significant part in the growth of digital inclusivity in India, an achievement the Modi government headlined during the G20 summit last year.

He notes that the India-China ties are viewed as disaster-prone when there are border clashes or when they confront/avoid each other in international forums. Nuances are often lost in the broad-stroke political rhetoric. While Chinese funding for Indian tech firms and NGOs is reported by the global media, the socio-economic relations between the two nations are often glossed over.

He notes that China succeeded in handling the 2008 global financial crisis far better than the Western countries. It experienced phenomenal growth in the first decade of this century. But he points out the flip side to this achievement — “appalling income disparities, rising unemployment, displacement of rural populations, pervasive corruption, criminality, massive environmental degradation, pockets of extreme poverty, social sickness, discontent of the have-nots and restive minorities in the Tibet and Xinjiang regions.”

Ramachandaran was one of the many ‘expats’ working in the Chinese media between 2008 and 2015. These foreigners who had lost jobs in the West and elsewhere, he says “kept an eye on each other” to report to the Chinese bosses. Interesting, but also risky.

He draws hitherto less-known comparisons between working for the China Daily, Global Times and other publications. Money and perks were more at the former where the official line was strictly followed than in the latter, where money was less but freedom was relatively more. He recalls writing, and being accepted on local issues and even being critical of the official line. To his surprise, he was told that he was “not critical enough”.

With the constant refrain of not letting the United States push or influence India’s China policy and that China must “create conditions for the neighbours to pursue reconciliation in their mutual interest”, Shastri presents a conflict resolution-oriented proposition. Indeed, with this book, he has created a counter-view to the prevalent India-China discourse that is set within the binaries of a zero-sum game.

For more details visit us: https://lokmarg.com/