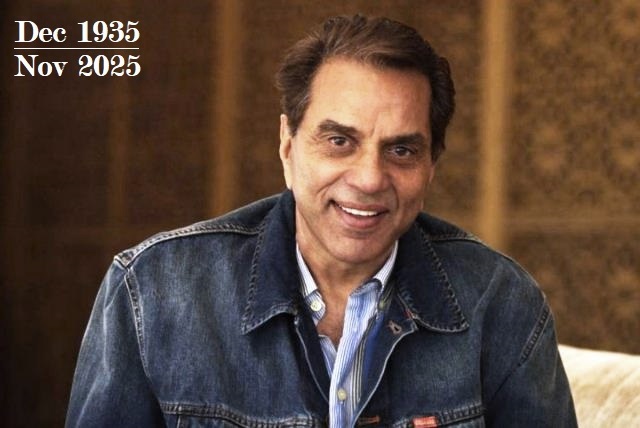

Dharmendra’s screen legacy cannot be confined to a single archetype. He was indeed the He-Man of Indian cinema, but that title often obscures the quiet brilliance he brought to sensitive, soft roles. His gentleness was never ornamental; it was integral, shaping some of the most memorable characters of Hindi film history.

In an era where masculinity is being re-evaluated, Dharmendra’s body of work offers a blueprint that strength and sensitivity are not opposites but complements. And perhaps that is his greatest achievement, proving that the toughest heroes can have the softest hearts.

For generations of Hindi film audiences, Dharmendra has been synonymous with the title “He-Man”, a signature born from his rugged good looks, muscular presence and the tough, unflinching characters he essayed in scores of action and drama films. Yet, to view Dharmendra only through the prism of virility is to ignore an equally remarkable facet of his artistry that is the sensitive, soft-edged, emotionally nuanced characters he played with rare grace, especially in the first two decades of his career. If the He-Man defined his public image, the tender man defined his cinematic soul.

Across a career spanning nearly seven decades, Dharmendra displayed a spectrum of emotional depth that few leading men of mainstream Hindi cinema could match. Long before the action star of Sholay (1975) or Dharam-Veer (1977) emerged, the actor from Punjab had already sculpted a reputation as the face of vulnerability, of a man whose silences spoke as powerfully as his later punches.

A Poet at Heart in the Early Years

In the early 1960s, Dharmendra became the preferred face of filmmakers who wanted a hero that could embody restraint, gentleness and introspection. He was strikingly handsome, but not in a way that overpowered the role; rather, he seemed to dissolve into the emotional undercurrents of his characters.

One of the earliest examples was Anupama (1966), where he played the quietly encouraging writer Ashok. With minimal dialogue and expressive eyes, Dharmendra conveyed empathy, patience and warmth, the qualities that made his chemistry with Sharmila Tagore feel timeless. Similarly, in Majhli Didi (1967), he portrayed a compassionate schoolteacher whose humanity held the film’s emotional center. And of course how could one forget Dr Deven in Bimal Roy’s iconic film Bandini, where the jail doctor proposes to a women prisoner.

ALSO READ: Chupke Chupke – The Comedy of Professors

In Baharein Phir Bhi Aayengi (1966), Dharmendra again balanced idealism with tenderness. As a journalist committed to truth, he stayed soft-spoken even in confrontation, playing the role with a gentle smolder rather than aggression. Naya Zamana (1971) repeated this template of the sensitive poet standing up for love, dignity and justice.

The Satyakam Peak: A Masterclass in Emotional Complexity

If one film must be chosen to represent Dharmendra’s sensitive-actor peak, it is Satyakam (1969). Directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee, the film remains a landmark in Hindi cinema for its moral complexity and emotional depth. Dharmendra’s Satyapriya Acharya, an idealistic engineer unable to compromise with a corrupt world, remains one of the most layered performances delivered by any commercial star.

Here, vulnerability was not just a trait; it was the backbone of the narrative. Dharmendra brought quiet turmoil, dignity, internal conflict and ultimately tragic integrity to the role. Many critics still describe his performance in Satyakam as one of the finest in the history of Hindi cinema, a role that proved the He-Man was equally a humane man.

Softness Even in Tough Roles

A fascinating element of Dharmendra’s career is that even when he played characters with grit, there was often a core of tenderness within them. Phool Aur Pathar (1966), the film that established his macho image, is a perfect example. He played Shaka, a rugged criminal whose exterior is softened when he encounters a neglected widow (Meena Kumari). Dharmendra’s transformation from hardened loner to a man of compassion was marked by emotional restraint rather than melodramatic flourish.

In Sharafat (1970) and Chaitali (1975), he again portrayed men whose gentleness broke through challenging circumstances. His eyes, expressive to the point of being poetic, became his primary tool for communicating empathy.

A Hero Women Confided In

Dharmendra’s sensitive roles often made him the confidant or emotional anchor of women protagonists. In Mamta (1966) and Khamoshi (1969), his characters functioned not as dominating male leads but as emotional complements to powerful female narratives. His presence offered comfort, understanding and stability, rare qualities for male stars at the time.

This quality of being soft without being weak, comforting without losing screen presence cemented Dharmendra as one of Hindi cinema’s most versatile stars.

Reinvention Across Decades

While the 1970s and 1980s leaned heavily into his action persona, Dharmendra’s sensitivity resurfaced at various points. Films like Ek Mahal Ho Sapnon Ka (1975) carried echoes of his earlier poetic charm. Even in ensemble dramas or masala entertainers, he infused emotional honesty into his roles, keeping the softer Dharmendra alive beneath the He-Man exterior.

What makes his longevity remarkable is not just physical presence but emotional adaptability. The same actor who leapt across trains in Sholay could break hearts with a single glance in Anupama.

A Full-Circle Moment in Modern Cinema

In 2023, more than 60 years after his debut, Dharmendra moved audiences yet again in Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani. As Kanwal Lund, an elderly man rediscovering love and dignity, he offered a performance rich with vulnerability and dignity. His portrayal reminded younger audiences of the actor he was in the 1960s, the gentle romantic, the soft-spoken poet, the emotional anchor.

It was not just nostalgia; it was a reaffirmation that sensitivity had always been Dharmendra’s superpower, not his muscle power.

(Sidharth Mishra is an author, academician and president of the Centre for Reforms, Development & Justice)