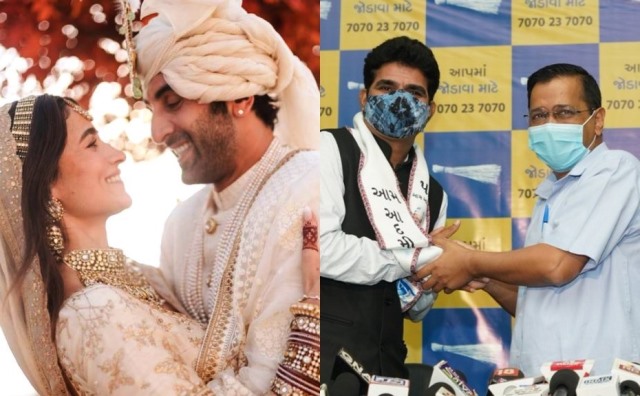

When a Bollywood actor gets married, the Indian mainstream media goes bananas. And if both the parties getting hitched are Bollywood actors, the media frenzy can reach ludicrous proportions. So last week when Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt, both actors of some repute, got married in Mumbai, the paparazzi and reporters got so wild at the venue of the wedding–at Kapoor’s residence in a tony Mumbai locality in Bandra–that neighbours had to complain to the authorities to quell the crowds and the disturbing activity.

Indians’ craze over anything Bollywood is well known. The entertainment sections of newspapers and other publications in India are almost solely devoted to covering the Indian film industry, which easily produces the largest number of films in the world. Every year, there are at least 800 films produced in Bollywood and the number of box office tickets sold exceeds four billion. These are mind-boggling statistics but Bollywood’s influence and dominance in India’s culture looms larger than anything else.

Nothing wrong with that. But it is when the media-created hyperbole reaches frenzied levels that everything gets puzzlingly out of control. Last week, anyone trying to read or watch the news in India would have been assailed by stories related to the celebrity wedding. Besides the one about how the media activity disturbed the peace in the neighbourhood of the wedding’s venue, there were other more ridiculous stories. One that particularly stood out was about how Bhatt’s chauffeur was so emotionally moved by his employer’s wedding that he declared that he would be “there for her” always.

In case you thought such stories got published in tabloids and gossip blogs alone, think again. Some of India’s leading newspapers found space on the front pages of their publications or high up on their websites to splash such stories. So we learnt that when the bride dropped the kaleera on the heads of her bridesmaid and it fell on the groom’s cousin, Karishma Kapoor’s head, the 47-year-old, who is also an actor, was ecstatic. These and other trivial details about the wedding (example: the size of the blouse that actor Priyanka Chopra wore when she came to the ceremony) were provided eagerly by Indian media.

One reason for the media’s hell-for-leather approach to cover celebrity events, particularly weddings of the rich and famous, is probably frustration. Even though India prides itself as a large and diverse democracy, the media, no matter what anyone says, is as good as being muzzled. According to a ranking by Reporters without Borders, India ranked at 142 out of 180 countries that the survey covered. And it was judged as one of the “world’s most dangerous countries for journalists trying to do their job properly”.

The thing is that most media publications and their journalists are not really affected by the dangers of working in India. That is because they choose not to do their jobs properly. It is difficult to find stories or coverage in Indian media that is even mildly critical of the authorities and the government. Blatant violations of human rights, alarmingly growing incidents of communal, caste, or religion based discrimination, which is often marked by horrendous violence, are reported but rarely do the influential publications take a stance of condemning them.

The reason why India’s media has turned into wimpish lap dogs is not rooted in ideology, ethics or morals. It is squarely economics that has turned large and influential media houses into lackeys of those in power. First, there is the revenue angle. India’s publications, particularly those that are printed, depend highly on advertising revenues to survive. With e-commerce and online transactions fast replacing traditional forms of selling and buying, a large chunk of advertising revenues have disappeared as companies, particularly those that market consumer products, seek online channels to promote, advertise and sell their products more effectively and cheaply. This has meant that much of the conventional advertising that media groups survive on is government advertising: appointment ads, statutory tenders, notices, and advertising by public sector entities that are remotely controlled by government ministries.

It is not difficult for strong governments–India’s current regime at the Centre, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), is probably one of the most powerful in the country’s independent history–to control or get the media to toe the line. There is another reason for that. Most large media organisations in India are owned by business families or entrepreneurs. Some have other business interests. Many have political ambitions. Staying on the right side of powerful authorities often makes sense for them.

If you talk to the average Indian–poor or middle-class–the constant refrain you will hear about today is how inflation is hurting their budgets. In the aftermath of the havoc wreaked by successive waves of Covid, prices of almost everything have soared: petrol, diesel, food, everything. But it is curious that in-depth coverage of this inflationary trend and its impact on the overwhelming majority of 1.4 billion Indians are few and far between when it comes to the mainstream media.

This is just one example of media apathy. When majoritarian violence is directed against minorities, or there is a controversy as there was recently about Muslim women wearing hijabs, or regarding the sale of halal foods, the media does cover it of course but besides poker-faced reporting of the facts there is little attempt to point fingers or hold a mirror to the authorities who are often hapless or neglectful in their actions related to these incidents. India’s media is failing Indians.

AAP Now Eyes Other States

After the Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) impressive victory in Punjab’s state elections, it is now eyeing two more states–Gujarat, which goes to polls in December, and Himachal Pradesh, which will hold elections in November. In both states, it is a BJP government that is in power. And while Himachal Pradesh is a smaller state with 68 seats than Gujarat, which has 182 seats, it is unlikely that either of the contests is going to be easy for AAP.

But early-stage campaigning has begun in earnest. AAP’s supremo and Delhi’s chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, and his colleague and Punjab chief minister Bhagwant Mann, have been making visits to these states, particularly Gujarat, which is considered a powerful base for the BJP and has had Narendra Modi as its longest-serving chief minister for more than 12 years.

The two state elections will be watched keenly. If AAP can make an inroad into either of the states it will be a huge victory for the party. But more than that, it could change the dynamics of politics in the country. That is because it would be the stepping stone for a regional or small party such as AAP towards becoming a national player. It is too early to place bets on what is likely to be the outcome of these elections. However, one thing is fairly certain: the main fight in both states would be between AAP, the challenger, and the reigning champion, the BJP. In case you are thinking about the Congress, the sad truth is that its story is nearly over.