Pakistan has urged Bangladesh, its erstwhile eastern province, to “clean your hearts and move on”. But a just-launched documentary film revives the horrors of the ‘genocide’ that preceded their violent separation in 1971.

The two events of last month underscore the dogged reluctance of the perpetrators to acknowledge the crime and of the victims who find it hard to forget it. It is a universal story. Forever glossed over, even justified, the genocide – wilful killing of unarmed innocents – has been a part and parcel of human evolution, spanning greed for territorial, political and economic gains, to religion, ethnicity, and colonisation. Its perpetrators are the rich and the powerful, who control knowledge and communication. The ideological divide is irrelevant since atrocities have been committed by both the Left and the Right.

Take the present. When the man currently presiding over the most powerful nation claims to have ‘ended’ seven conflicts, blows hot and cold over two more in Ukraine and India-Pakistan, and desires to be given the peace Nobel, his silence on Gaza is deafening. This has indeed helped perpetrate a genocide in which 63,000 have already been killed.

Besides those that preceded or followed the two World Wars, the Political Instability Task Force estimates that 43 genocides occurred between 1956 and 2016, resulting in 50 million deaths. The UNHCR estimates that such episodes of violence have displaced a further 50 million. The Rohingyas are a continuing story, with estimates of 25,000 to 43,000 being killed so far.

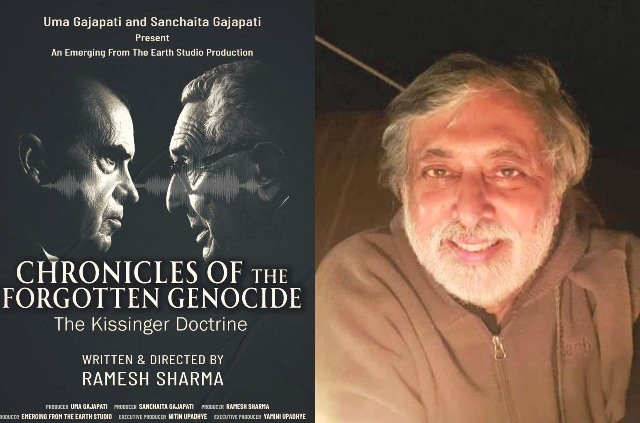

Bangladesh figures in veteran Indian filmmaker Ramesh Sharma’s aptly-named documentary, Chronicles of the Forgotten Genocide, is one of the ten ‘forgotten’ genocides of the last century, the others include the Nazi Holocaust, Armenia, Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, the wartime killings of the Kurdish populations by Saddam Hussein in 1987-1988 during the Iran-Iraq war and gypsy populations.

In Bangladesh, the tragic events unfolded in 1971 when talks for forming a government in Pakistan after the elections broke down. “Operation Searchlight” was launched on the night of March 25-26 after President Yahya Khan asked the East Pakistan authorities to “sort them out.”

An estimated three million people were killed, and over 200,000 women were violated. Another ten million were forced to flee to India.

ALSO READ: Is Bangladesh’s History Headed For A Revision

Pakistan wants to gloss over what its soldiers and their Islamist ‘collaborators’ did that year. Emboldened by last year’s regime change, visiting Pakistani Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar asked that the Bangladeshis “clean your hearts and move on.” His plea has divided the people who cling to old memories, even as they deal with the growing presence of the Islamists around the current caretaker government.

Sharma’s film records that the United States, under the Richard Nixon-Henry Kissinger duo, was supportive of Yahya Khan because he was the principal conduit for Washington that was keen to establish relations with China.

Because of these plans, the US ignored reports of its Consul General in Dhaka, Archer Blood, who gave graphic details from the ground and warned of the ongoing massacre of the unarmed people. They were later recorded in “The Blood Telegrams” by journalist-turned-academic, Gary Bass.

The world learnt of the military operation and mass killings only on June 13 – 74 days after it began – when The Sunday Times of London published a centre-spread report by the West Pakistani journalist Anthony Mascarenhas. He moved to Britain to write the true story. In this report titled ‘Genocide’, Mascarenhas wrote, “General Yahya Khan’s military government is pushing through its own ‘final solution’ of the East Bengal problem.”

Ramesh Sharma’s film interviews many key officers, post-retirement, who were stationed in Dhaka, Islamabad and New Delhi. They were those who monitored events and warned of the worst. But Washington suppressed them.

The most searching and prophetic was Archer Blood. “Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities… Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy.”

In his book The Blood Telegram, Bass records the reasons why: “Unfortunately, the United States refused to respond because of Pakistan’s status as a Cold War ally. President Nixon, taking on a flippant and discriminatory attitude, regarded the genocide as a trivial matter, assuming a disinterested American public due to the race and religion of the victims. His belief that no one would care because the atrocities were happening to people of the Muslim faith created an uninformed and disconnected America concerning the Bengali genocide of 1971.”

The American government has never acknowledged the actions of the Pakistan Army as a genocide. Henry Kissinger, fully in the know, characterised it as unwise and immoral, but never termed it genocidal. As for the US military support to Islamabad, Nixon told Kissinger, “Hell, we’ve done worse.”

While Nixon had to resign because of the Watergate scandal, Kissinger, with whom he exchanged cuss words about Mujib and a resolutely defiant Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, lived to dominate more American administrations to carry out ‘cleansing’ in Chile, Cambodia and other countries where mass killings occurred. He was never tried or punished.

Sharma’s film also explores “Anatomy of the Coup”, which led to the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding leader of Bangladesh, in August 1975. With Kissinger calling the shots, he sees its connection with 1971.

Through in-depth analysis, rare archival material, and compelling narratives, the documentary sheds light on a crucial yet often overlooked chapter of South Asian history.

Bangladesh has suffered double irony. All efforts to establish justice for the 1971 victims halted after Mujib’s assassination. The War Crimes Tribunals that his daughter, Sheikh Hasina, set up to try the perpetrators of 1971 have now summoned her for trial for alleged killings and corruption when she was in power.

As the world moves to more complex times in this century, the generations that suffered them or witnessed them, in Bangladesh or elsewhere, are fading. Time is taking its toll. Yet another genocide saga will fade – unfortunately, with some underway and likely more on the cards.

One would have to await the ‘return’ of academics who disagree, diplomats like Blood who dissent and journalists-scholars like Anthony Mascarenhas and Lawrence Lifschultz, who will show a mirror to the world. The human spirit endures.