The credit for the BRIC acronym goes to the then Goldman Sachs chief economist Jim O’Neill who in a paper in 2001 was quite hopeful about the future of economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China. Riding on the wave of globally shared optimism surrounding the BRIC nations, Goldman Sachs, the American multinational investment bank and financial services giant, launched the BRIC fund in June 2006 with routine hoopla. But by September 2015 – four years ahead of that South Africa came on board to make the acronym one letter bigger BRICS – the growth promise of the group sufficiently faded with Brazilian economy in slums, Russia struggling with low oil and commodity prices in general and China moving far away from double-digit growth.

The global financial crisis of 2008-09 also was a factor responsible for the fund managing a low average annual return of 3 per cent and underperforming the MSCI BRIC index. What, therefore, followed was the merging of the exclusive BRIC fund into a more diversified emerging market fund in October 2015.

At that point the Washington based think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies said in a report: “Conflicting interests and the indisputable political, social and cultural differences among the group’s members have kept the BRICS from translating their economic force into collective political power on the global stage… And with economic prospects decreasingly promising, the notion of the BRICS as a political project seems too fragile to stand on its own.”

Then at the launch of BRIC, the hope was the grouping would become the representative voice of the global south and emerge as a rival to G-7. That hope died very young as there never has been much in common in the motley group of five countries – while China and Russia have one party rule with Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin always having the last word, India as the world’s largest democracy would look better with the largest minority group not nursing the feeling of always getting a raw deal, Manipur not burning and the space for free airing of views not squeezed. The heterogeneity of BRICS is also underlined by their economic performances.

Referring to the highly contrasting phenomenon, The Economist says: “On average, the GDP of Brazil, Russia and South Africa has grown by less than 1 per cent annually since 2013 (versus around 6 per cent for China and India.)” Then somewhat acerbically, it writes “any investment analyst who picked them among the most promising emerging markets today would be laughed off her Zoom call.” In the meantime, the equation among members of BRICS continues to change. Since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and imposition of sanctions by Western countries, Russia has come to depend on Chinese diplomatic and strategic support like never before. At the same time, Indian refineries continue to reap a bonanza by importing Russian crude at highly discounted prices in the wake of the world’s third largest oil producer with a share of roughly 11 per cent of global supply finding some of its major traditional markets drying up because of sanction. What, however, must be a reason for discomfiture for New Delhi is Moscow virtually coming under Beijing wing.

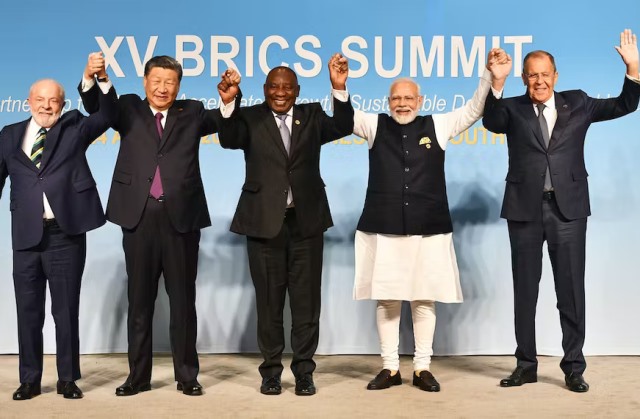

New Delhi’s uneasiness is heightened by Putin deciding not to attend the G-20 summit in spite of Modi making a request on phone. Putin’s excuse is that he will stay too preoccupied with domestic issues and also overseeing Ukraine war operation. Incidentally, the Russian President absented himself from Johannesburg 15th BRICS conference for fear of arrest since South Africa being a member of the International Criminal Court would be under obligation to execute the arrest warrant issued against Putin in March for alleged war crimes involving Ukraine. Russia in crisis affecting BRICS relevance in world affairs apart, China and India continuing to find themselves in diametrically opposite praxis on a host of issues are not helping the cause of global south.

This is best illustrated by contradictory statements emanating from New Delhi and Beijing on what led to the meeting of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of BRICS Johannesburg conference. The Chinese foreign ministry says the meeting happened following an Indian request provoking a riposte from New Delhi that there was a pending request for a meeting from Beijing.

China has described the Modi-Li conversation as a “candid and in-depth exchange of views.” In diplomatic phraseology, candid does not leave room for amicability. New Delhi, on the other hand, said the conversation was “informal.” The two leaders, as transpired from what emanated from the two capitals, mainly discussed the border issue, which has defied settlement. On the subject, New Delhi says, Modi and Ji have agreed to “direct their relevant officials to intensify efforts at expeditious disengagement and de-escalation.” But Beijing maintains that the two countries will have to “bear in mind the overall interests of their bilateral relations and handle properly the border issue so as to jointly safeguard peace and tranquillity in the border region.”

ALSO READ: BRICS Expansion, Geopolitics And India

Now within a few days of that meeting and the statements on unresolved border issues (contradictory in some ways) that followed, China to India’s disappointment released its 2023 edition of “standard map” laying claims to ownership of Arunachal Pradesh and the Aksai Chin. This, however, is not the first time that China has been up to this trick. Is the release of the map showing Indian territories as its own amounts to a Chinese message that it is not committed to restore the April 2020 status quo in eastern Ladakh, where, according to some military veterans, it remains in occupation of around 2,000 sq km of Indian land?

Expectedly, India’s external affairs minister S Jaishankar has been dismissive of the Chinese claim and New Delhi has filed strongest possible protest using diplomatic channels. Jaishankar said: “China has even in the past put out maps which claim territories which are not China’s, which belong to other countries. This is an old habit of theirs… Making absurd claims doesn’t make other people’s territories yours.” Sadly, Beijing’s release of the map ahead of G-20 summit and soon after BRICS meet militates against relationship improvement of mighty neighbours. Chinese diplomacy has always been full of riddles, not easy to decipher. For a change and to India’s satisfaction, China agreed to the BRICS declaration describing the aspirations of India, Brazil and South Africa to play a bigger role in world bodies, including the UN Security Council.

The operative part of the declaration says: “We support a comprehensive reform of the UN, including its Security Council, with a view to making it more democratic, representative, effective and efficient, and to increase the representation of developing countries in the Council’s membership so that it can adequately respond to prevailing global challenges and support the three legitimate aspirations of emerging and developing countries from Africa, Asia and Latin America…” BRICS acknowledgement of G-20 as a premier multilateral forum is also of comfort to India, which this year is doing rotational presidency of the group.

BRICS will now be an 11-member organisation with the induction of four from the Gulf and West Asia comprising United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia from Africa and Argentina from South America. An expanded BRICS will no doubt carry more heft to engage with the West and leave its impact on future economic and trade reforms of the latter. BRICS has wasted much time in haranguing the West, often without provocation, which, however, was ignored.

But that should not have been the case since the grouping not only included the world’s second and fifth largest economies, but BRICS’ share of world GDP is now around 26 per cent, up from 8 per cent in 2001. Moreover, BRICS failed to capitalise on its combined population of 3.2 billion that is 41 per cent of the world. The only concrete thing to have emerged so far from BRICS is the Shanghai based New Development Bank (NDB or BRICS Bank). Well, NDB has not delivered the way it was hoped at its founding in 2015. But it will wrong to undermine the bank in any way. One positive is the joining of three members – Bangladesh, Egypt and the UAE. NDB has so far extended credit of $33 billion to nearly 100 projects. The non-starter was a common currency for BRICS. What is to be accepted is that none of BRICS constituents has the capacity to operate an exchange rate monetary policy regime.

Moreover, because of profound differences with China, India will not acquiesce to Chinese Yuan playing a big role in global trade, not to talk of Yuan becoming a reserve currency. As BRICS become bigger – likely Bangladesh and Indonesia will next come on board – the challenge will be to frame a programme, based on consensus and not by way of economic and political power of any constituent that will allow global south to work in harmony with the West. Now there is a challenge for the world’s most adroit scrabble player to write an appropriate acronym for the expanded BRICS.