It is finally curtains for Mughal-e-Azam, 62 years after it released on August 5, 1960. Dilip Kumar, who played the rebel prince Salim, died a year ago, at 98. Shapurji Palonji Mistry, who financed the film at great risk, passed away this month at 93. There is none who can talk, first-hand, about what all went into its making. Others who contributed to this film, rated as one of the greatest, if not India’s greatest-ever, left long ago.

Mughal-e-Azam has slipped into the realm of nostalgia, as part of India’s rich, century-plus, film culture. But there will always be critics and cineastes who enjoy cinema of a by-gone era. Anyone would agree that another Mughal-e-Azam cannot be made, just as you cannot re-make Cleopatra or Ten Commandments. Technology is available, but finances?

Over 80,000 feet of film footage had accumulated by the time it was completed, enough, it is said, to make four more Mughal-e-Azams. Even the current crop of the Mistry clan, though richer than it then was, would shudder at the risks involved in its re-making. And there is logic, not just nostalgia, which counsels against tinkering with classics.

Above all, where does one get a director like K Asif, nursing an unparalleled passion for the project for long years and at the end, delivering a masterpiece that generations have watched with awe?

Rare for a movie, Mughal-e-Azam is now a metaphor for those times. Six decades is a long time. The passage has changed values; more so in the recent times, sharply and divisively. It was part of the Idea of India as one has known.

That idea is being challenged now. Agreed, it is not all fact/document-based. There is history, and there is popular lore that has devolved over time. Essentially separate, but when they get enmeshed, and ideological agenda is tagged, confusion has arisen and disputes have occurred.

This is being re-written from the contemporary prism. While more information and research should be welcome, what we are witnessing are attempts to turn it into version of the victor – mind you, victory not of a king of a queen, but an electoral one in a democracy, subject to renewal every five years. Meant to suite a political agenda, it is being changed from the top, to percolate down, in the name of ‘nationalism’.

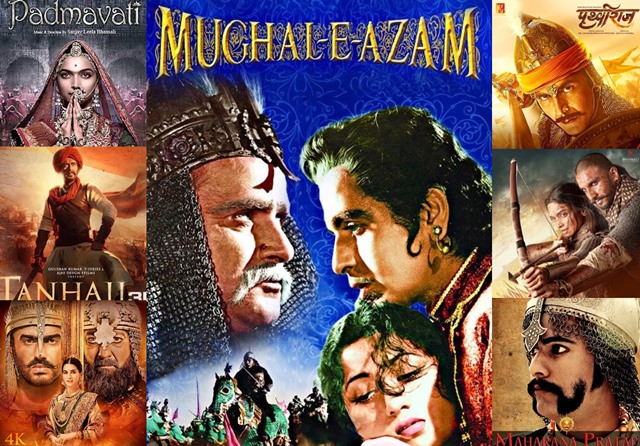

Cinema that remains India’s most popular and pervasive medium, is being co-opted in this. This is reflected in some recent films on subjects that deal with the past. They are not necessarily based on history. Even loud disclaimers that they are only ‘inspired’ or based on literature on those personalities, events and those times, have not prevented controversies, some of them turning violent.

“Hurt feelings” and “wounded pride” have been advanced among the reasons for protests. We have seen politics-laced controversies by people of one caste or community or the other.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali has been among the worst ‘offenders’ or ‘victims’, depending upon how one views his films. His Padmavat (2018) angered some Rajput groups. Bajirao Mastani (2015) dissatisfied some claimants of Maratha Empire’s glory. They felt Bajirao’s wife Kashibai was short-changed to glamourize Mastani. Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Devdas (2002) hurt Sharatchandra acolytes who found the England-returned protagonist outlandish.

ALSO READ: Pakeezah – The Courtesan Classic

Bhansali grew wiser by the time he made Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022). Nobody really wanted to own up a red light district’s ‘madam’. By comparison, Ashutosh Gowarikar has been lucky to escape controversy, though unlucky with his films’ success. Critics didn’t delve deep enough into the ancient Mohenjo Daro (2016). None was ‘hurt’ by his more recent Panipat (the 3rd battle, in 1761). That battle altered the course of history to a great extent, if not as much as the Battle of Plassey (1757). Afghanistan’s Ahmed Shah Durrani dealing a humiliating defeat on the Peshwa’s Martha army went unchallenged.

Samrat Prithviraj (2022) is, perhaps, a better ‘representative’ of the changed times. Claimed to be based on Prithviraj Raso composed in praise of the king by his favourite bard Chand Bardai, it has satisfied those who had pitched for ‘purity’ in the depiction of Rani Padmini or Padmavati. But it left the film audiences cold.

This could have been box office failure of a big-budget venture, except that its director, Chandra Prakash Dwivedi, injected controversy. The man who had made that brilliant serial, Chanakya, for Doordarshan long ago, found a political alibi for his financial flop. He reportedly blamed it on the theme being about “a Hindu king”.

This brings us back to Mughal-e-Azam, but not without touching upon Gowarikar’s immensely successful Jodhaa Akbar (2008). The most remarkable thing about that film is that it put a seal of confirmation on the message of Mughal-e-Azam. Mind you, based on available records and popular lore, neither claimed perfection in historical terms.

Both celebrated the story of Jalaluddin Mohammed Akbar (1556-1605 AD) the third Mughal Emperor and his Hindu Queen Jodhabai. Both films stressed on mutual respect and tolerance among the Muslim rulers and their Hindu subjects.

British academic, Professor Rachel Dwyer, author of the book Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema, says Mughal-e-Azam highlighted religious tolerance between Hindus and Muslims. Her examples include scenes depicting the presence of Queen Jodhabai, a woman and a Hindu, in Akbar’s court. Celebrating Janmashtami, Akbar is shown pulling a string to rock a swing with Krishna’s idol. Anarkali, the courtesan Salim loves and to get whom he rebels against the father, sings a Hindu devotional song.

It wasn’t ‘secularism’ as we know it today. Akbar’s move was political, driven by enlightenment and not by altruism. History calls him ‘Great’ because rather than fight the Rajputs, he had consciously struck alliances with them.

Akbar is not-so-great and Mughals are the villains today. Social media, some of it owned by major media houses, is full of calumny against them. Historical accounts of Akbar’s defeating Mewar’s Maharana Pratap in the Battle of Haldighati (1576) are being disputed. Already, some history books declare Pratap the victor.

Again, it was a significant military effort by Akbar to establish his rule across India’s North. The Haldighati battle is a case-study at the Indian Army’s College of Warfare. If Akbar had Hindu generals, Pratap had Muslims. Now, it is viewed as a clash of communities.

This type of jingoism begets extreme reaction, equally guilty of distortion. Akbar is called a ‘fake’ Muslim who blocked his son from marrying Anarkali, a Muslim, but allowed idolatry by Hindu wife Jodhabai.

Agreed, that those who control the present can rewrite the past. But as George Orwell says: “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com