The year 2025 has witnessed more discourse on the “Elephant-Dragon tango” about India and China than in recent years, with the phrase being approvingly mouthed by their top leaders. Notably, this is positively hyphenated and not one of “elephant versus dragon”.

As India seeks to bridge the significant gap that exists with China, differences persist and are unlikely to disappear soon. But they are not being gloated over, as they race towards completing their respective centuries of independence in 2047 and 2050.

This has been spurred by a series of events, not the least the Donald Trump-led United States threatening allies and adversaries alike, and selectively ‘tariffing’ them. Singled out for some of the ‘punishment’, India has taken some rear-guard actions, like warming up to the China-led SCO, which has only rattled Trump more. Having experienced its disruptive nature, the much-speculated ‘thaw’ in India-China ties is likely to continue even after the tariff war ends, sooner or later.

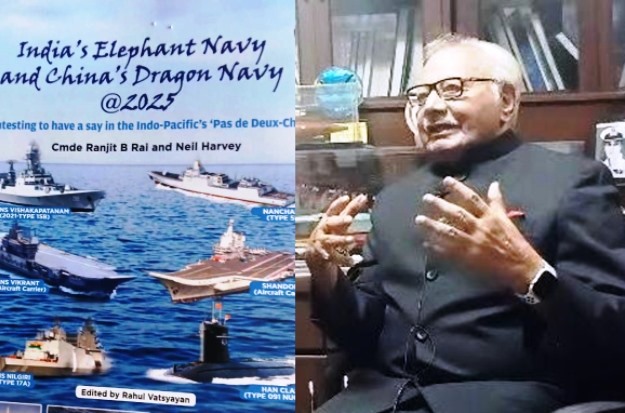

This is the crux of the Indo-Pacific region’s pas de deux churn, reflected in the way Asia’s two largest navies are shaping. A deeply insightful compare-and-contrast study, India’s Elephant Navy and China’s Dragon Navy @ 2025, emphasises that this process is set to expand and impact the world.

Authored by Commodore Ranjit B. Rai (rtd.), an Indian Navy veteran and Neil Harvey, a Briton with a deep interest in naval affairs, the study neither ignores nor mocks the vast gap in the two navies. Nor, for that matter, their respective strength and flaws.

It provides a new prism to Asian naval affairs, a rare regional insight in an area of geostrategic study where information and deliberate disinformation. It is unfiltered, richly illustrated, and what is more, intellectually grounded. Any student of naval affairs, anywhere, needs to study it since the balance of power, including naval power, is shifting to the Asia-Pacific region, and this is going to be the “Century of the Seas”.

India’s Atmanirbhar (self-reliance) is caught between a weakening Europe struggling to retain its global relevance, Trump’s MAGA and Xi-led China’s long-term dream, Zongguo Meng. This is a world where leading nations, wherein he includes India, are led by “near dictators” willing to take risks, set new red lines against their respective adversaries, and those with N-power, including the US, are piling up their arsenals.

Rai makes ominous, but starkly believable, predictions of more of Gaza, Ukraine and Op Sindoor-type conflicts occurring across the globe in the coming years. This is because the US has become ‘impotent’ in policing peace in failing to deliver the promised peace in Ukraine, and its penchant for keeping the Middle East on the boil.

He foresees rapid realignments in a world where yesterday’s UN-sanctioned terrorists are being courted by powers big and small, since the UN itself has ceased to be relevant as a consensus-builder, let alone a peace-maker, as respect for international law is virtually absent.

With a nuclear-armed Pakistan willing to sell whatever it has to the Islamic world and access to the US in the Arabian Sea, Rai says a North Korea-type regime may be in the offing in Islamabad. He wonders how China, having already invested big in the region and preparing to move into Afghanistan before the US returns, will tackle its “all-weather ally.” The two confront India.

The real juice of his 280-page, largely technical, treatise is in his India-China assessment. “With memories of the 1962 War and Galwan 2020 still fresh, India’s elephant moves slowly but surely. China’s dragon spits fire, illegally controls and arms the South China Sea islands, and employs cyber and strategic moves to rise without war. China supports Pakistan – India’s bete noire, and more recently, Bangladesh,” he says.

But he counters: “India holds the Bolt and the Key to the Malacca Straits” and calls it “China’s Malacca Dilemma.”

China’s world’s largest navy (PLAN) has 367 ships and an extensive Naval Air Fleet with three aircraft carriers. The Indian Navy has 144 ships, two aircraft carriers, and a 225-aircraft naval air arm, with 50 (now 61) platforms on order, all in Indian yards, saving foreign exchange and providing mass employment. The Indian Navy’s target is 170 ships and 300 aircraft by 2027, when 26 Rafales will have joined, along with more large drones.

ALSO READ: Indian Navy@2025 – Riding The Waves

The book examines the rapid modernisation of both fleets—India’s aircraft carriers INS Vikrant and INS Vishakhapatnam class destroyers on one hand, and China’s Shandong carrier and Type 055 cruisers on the other. Comparing the two, Commodore C. Uday Bhaskar (rtd.) writes: “China holds more cards than India at this point.”

Yet, India’s diplomatic language about China has become more pragmatic. Officials describe relations as “on the mend,” with confidence in a “continued thawing” and prospects for being “back on track.” However, India reiterates its core concerns, particularly emphasising the need for de-escalation and permanent solutions to the border dispute in areas like Demchok and Depsang—highlighting that trust will require “structured de-escalation” and renewed high-level dialogue around the unresolved boundary issues.

Despite a more positive tone, both sides acknowledge that achieving durable progress will be difficult. The unresolved border remains the most sensitive issue, described as the main source of misunderstanding and mistrust. China’s official commentary emphasises the need for a “reliable border trust mechanism” and warns against external influences—particularly urging India to ignore US-led efforts to create divisions in Asia.

China’s call for a “Dragon-Elephant Tango” signals a desire for a new chapter in India-China relations, rooted in mutual respect, pragmatic cooperation, and strategic autonomy from external powers. Yet, both sides recognise that lasting normalcy will depend on sustained effort to resolve legacy issues and manage renewed engagement in a fundamentally altered geopolitical landscape.

In sum, when China, with Putin-led Russia as its ally, along with BRICS nations, offers an alternative to the US, for the first time since the “Cold War” era, Beijing and Delhi’s signalling a diplomatic reset with an eye on a global order beyond US Influence is important.

a better understanding, Rai rightly says Indians know little about their Himalayan neighbour. The two are “like chalk and cheese” in the philosophies evolved over the millennia, in their physical appearances and food habits, and in work cultures. He quotes Henry Kissinger, that while Indians play chess, or Chaturanga, which allows for a draw, the Chinese board game, Weiqi, does not.

Riding PM Narendra Modi’s Hindutva politico-religious platform, India has to meet multiple challenges on multiple fronts, a new one opened by an adversarial Bangladesh that has opened its Myanmar flank to global geopolitical shenanigans. Modi seeks a change in the way Indians think. Will that happen?