Cattle-breeders of Patri and surrounding villages in Gujarat’s Kutchh district produce 20,000 litres of milk earning a whopping ₹700,000 daily. Chilled and transported, it adds to the national grid of millions of litres marketed across the country.

Prosperous Patri is but a microcosm of the White Revolution that began in 1949 in a run-down creamery in Anand in Kaira (now Kheda) district. Today, the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) launched in 1950, is the world’s largest milk cooperative. Marketing ‘Amul’ brand of milk and dairy products, it registered a turnover of Rs 39,248 crore in 2020-21. It is the world’s eighth largest among the top 20 global dairy processors assessed by the International Farm Comparison Network (IFCN).

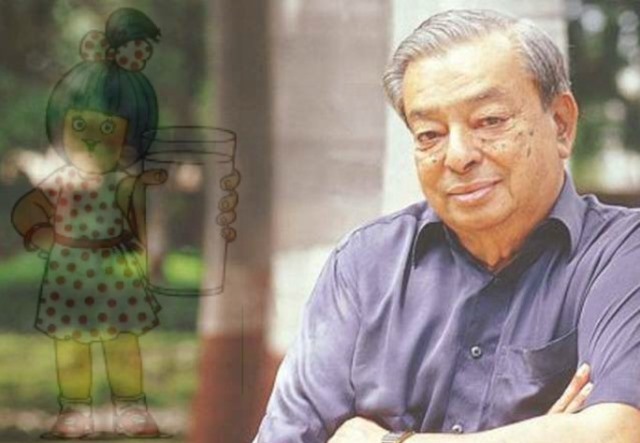

In mythology (Krishna and his love for butter), or in history, India may or may not have been the land of abundant milk. But at Independence, it had the world’s largest cattle population, and also millions of humans with no access to milk. That need was met through long years of cooperative effort. But the man who pioneered it, Dr Verghese Kurien, is a forgotten man in his birth centenary year.

A US-trained metallurgist from distant Kerala, Kurien arrived in Gujarat in 1949. How he fought the feudal, business and MNC interests and motivated farmers ignorant of their strength is a saga that stretches from the dawn of India’s Independence to the present.

Kurien and his team invented the process of making milk powder and condensed milk from buffalo’s milk instead of cow’s milk. Amul successfully competed against Nestle, the MNC that only used cow’s milk to make powder and condensed milk. In India, buffalo’s milk is the main raw material unlike Europe where cow’s milk is abundant.

Opening the first Amul “factory” in Anand, Jawaharlal Nehru hugged Kurien for his ground-breaking work. Kurien networked with successive governments to push his projects. A hard taskmaster, he could be blunt, even ruthless.

In his lifetime, India had become the world’s largest milk producer by 1998, surpassing the United States of America, with about 17 percent of global output in 2010–2011. But Kurien died in 2012, age 90, a disappointed man, saying that he did not like milk and did not consume it.

Three days before his death, renowned IT entrepreneur N.R. Narayana Murthy sought India’s highest civilian award for Kurien. He said: “A civilised society must show gratitude when people can sense it, or it is no gratitude at all. If our country does not stand and salute Verghese Kurien with a Bharat Ratna, I don’t know who else deserves it.”

That honour has eluded Kurien. He did get Ramon Magsaysay Award much earlier in 1963, and many more. The nation (read successive governments) have stopped short at Padma Vibhushan, the second-highest in 1999. Was it because he had lobbied hard, but unsuccessfully, to block the entry of foreign multinational corporations (MNCs) in India’s dairying sector? If that is so, perish the thought of his ever getting a much-deserved Nobel.

Kurien was crucial in replicating the “Anand Model” of cooperatives across India and beyond. In 1979, Alexei Kosygin invited Kurien to the Soviet Union for advice on its cooperatives. In 1982, Pakistan invited him to set up dairy cooperatives, where he led a World Bank mission. Around 1989, China implemented its own Operation Flood-like programme with Kurien’s help and the World Food Programme. Indian premier Narasimha Rao sent him to set up a dairy cooperative in Sri Lanka.

But during Rao’s regime and thereafter, Kurien and his ideas began to be discarded by governments keen on shedding the ‘socialist’ cooperatives approach and inviting foreign funds and participation as part of the economic reforms. Critics called his managing and planning ‘dictatorial’. If these reforms that are now integral to India’s progress, have had a ‘victim’, it was Kurien.

The path was opened, under pressures from governments, by Kurien’s own long-time protégé, Amrita Patel. While Amul and its Indian half-sister Mother Dairy continue to dominate the market of milk and milk products, the MNCs are also having a heyday.

It is no longer fashionable to berate the MNCs in dairying or farm sector, but at the ground level, it does betray seemingly misplaced priorities, when milk is diverted to making ice cream and potatoes to make chips. There is a global sop, however: Amul’s curd and paneer, the Indian cheese, are attracting health-conscious Americans. High in protein and fat, Paneer is a favorite among those on the keto diet, a market valued at $9.5 billion in 2019.

The concept of cooperative itself has undergone change. Dominated by politicians guided only by profit motives, the farmer/producer no longer calls the shots. The marketing guy in the Board Room does.

Looking back, Kurien was a product of the Cold War era. Mother Dairy separated from Amul, the brand name the two had nurtured. Both are doing well — so are the MNCs. This underscores the tussle between the urban India and the farming Bharat — and not only in dairying. The unease in their co-existence is palpable.

Some of these and other conflicting interests and contradictions in the larger farm sector are behind the three controversial farm laws. The Modi Government first rammed them through the parliament, but after a year-long agitation, has withdrawn them. This is not out of love for the farmers, 700 of whom died during the agitation, but for winning votes in the forthcoming elections.

The producers of fruits, vegetables and cereals have failed to unite and form their cooperative retail outlets just as Amul did in the dairy sector. This would be more profitable and economical for both the producers and the consumers. Perhaps, it needs another Kurien.

Reforms are needed in each of these sectors. But the “human face” with which they were begun, howsoever imperfectly, is missing. There is something brazen about all this, even immoral, if morality is at all a consideration in the way people who toil and produce are, or should be, treated in a society.

The past and the present still coalesce in some ways. To tell his story to the world, Kurien co-wrote a feature film, Manthan (Churning), in 1976. Anand’s co-operators chipped in with ₹2 each. Directed by Shyam Benegal, it won both critical acclaim and money. A classic, the UNDP screened it to start similar cooperatives in Latin America and in Africa.

Amul is the first cooperative sector product, perhaps a global first, to be advertised on modern lines. The success of “utterly, butterly delicious — Amul” line remains the envy of the India Inc and the MNCs.

Amul has spelt both health and humour for half a century now. It has served delicious butter but also taught Indians to be witty and laugh at themselves. The little moppet in a red polka-dot dress and a blue ponytail has delivered on a regular basis a humorous take on everything that bothers Indians, everything that deserves a repartee.

Like a true spokesperson of the masses, she rises to every occasion, be it a cricketing double century, scandals surrounding politicians, to controversial diplomatic policies, with an infallible gut and tongue-in-cheek attitude. In the process, Brand Amul has become synonymous with honesty, purity and subtlety. As its advertiser, Kurien never pre-viewed them.

Come to think of it, Kurien’s was the first real cooperative success in an era with controls — long before humour-less economic reforms and information technology and telecom happened to India.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com