The repair, resurrection and re-release of the film Manthan last month matched India’s political churning as toxic, divisive, yet aspirational elections neared the end.

The 1976 classic was part of India’s big splash at the 77th Cannes Film Festival. It was important as it came from France, the birthplace of cinema. It also recognised the few quality films out of over 2,400 films made last year. They helped the waving of the flag. But they also sent multiple messages that need to be noted.

Cannes was unique because its entries won in different categories. The one in the competition section entered after a 30-year gap, received applause for eight long minutes. Their appearances are not to be belittled, India is no longer confined to Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, Priyanka Chopra and others walking the red carpet.

Take the films first before reading the messages. In each of the three competitive sections, India won a major award. Grand Prix, the second-most award went to Payal Kapadia-directed All We Imagine As Light. It is an ode to Mumbai, the birthplace of Indian Cinema and despite its many flaws – Urbs Prima in Indis – India’s premier city. The three women protagonists who are there to make a living amidst chaos are portrayed by less-known actors – none from ‘Bollywood’.

This is ‘independent’ cinema and bears some comparison with the ‘parallel’ or New Wave cinema of the 1970s and 1980s. Manthan was one of the outstanding products of that era. Hopefully, the new string of successes may see some of the big money invested in commercial cinema getting diverted to such efforts.

Kapadia’s film bagged the second-most prestigious prize of the festival after the Palme d’Or, which went to American director Sean Baker for Anora. An AFP report says Baker and his films were “hot favourites” but the victory was “surprising as many expected either the gentle Indian drama or the Iranian film The Seed of the Sacred Fig to win.”

Cannes, it seemed, celebrated India last month and the Indians did not belie the expectations. Kapadia’s win shows poor public memory and poorer attention to documentary cinema. In 2021, her acclaimed documentary A Night of Knowing Nothing premiered at Director’s Fortnight and won the Oeil d’Or (Golden Eye) award.

She is an alumna of the Government of India-run Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). Called “anti-national” and punished for leading the protest against its then leadership, she took less than nine years to prove her mettle. Two more graduates have brought FTII glory. Chidananda S. Naik’s Sunflowers Were the First Ones to Know… won the La Cinef first prize. And Santosh Sivan was bestowed the lifetime Pierre Angenieux Excellence in Cinematography award. Need one say anything more about FTII?

Many foreign awards have marked India’s century-plus cinematic journey. But few remember that they won global applause even before Independence. The first to be shown at an international film festival was Seeta a Bengali film directed by Debaki Bose. It won an honorary diploma at the 2nd Venice International Film Festival in 1934. Sadly, Bose’s feat, like many by Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Gautam Ghosh and others from Bengal, accused of “selling India’s poverty to the West”, goes unnoticed by what is arguably called the “Indian film industry”.

In 1946 came Chetan Anand-directed Neecha Nagar. At the first Cannes Film Festival, it shared the Grand Prix with eleven of the 18 entered feature films. It remains the only Indian film to be awarded a Palme d’Or.

Entries at Cannes last month showed international mingling of talent. The Best Actress Award, the first by an Indian at Cannes, went to Kolkata-born Anasuya Sengupta. She worked with Bulgarian filmmaker Konstantin Boijanov for a Hindi film, The Shameless. It is inspired by William Dalrymple’s Nine Lives. Neither Boijanov nor Dalrymple, a celebrity chronicler of South Asian history, is stranger to India and the world.

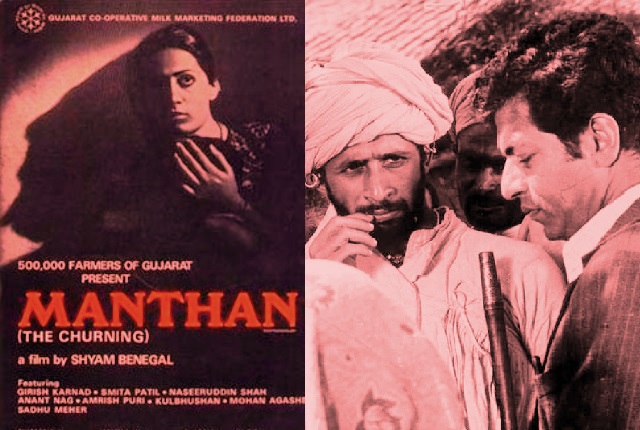

Manthan has been restored by the Film Heritage Foundation. One recalls the buzz Manthan caused when shown at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in 1977. It was a poignant moment for Naseeruddin Shah, who had debuted as an actor when he led the team at Cannes.

Among the few ‘survivors’ spared by the ravages of time are director Shyam Benegal, now 89, and cinematographer Govind Nihalani, 83. Tracing the “crazy journey” 48 years ago, Benegal says: “Now I can sit back as an old man and say, we did that.” The film achieved an impact that most entertainment films don’t. It’s by far my most influential work, he says.

ALSO READ: Verghese Kurien – Showing The Milky Way

Come to think of it, Manthan was a propaganda film meant to promote milk cooperatives after their success in Gujarat. It is a far cry from the present-day films that engage in political propaganda, try to re-write or sidestep history and spread hatred.

Herein lies the larger message of India’s own ‘Manthan’ – the churning – as a nation that stresses synergy, not separateness.

It is about two ‘revolutions’ – ‘white’ of the milk, pioneered by Verghese Kurien and ‘green’ in the farm sector by MS Swaminathan. Benegal says: “To me, he (Kurien) was one of the two greatest men who helped develop the country in the first 50 years of independent India. The other was Swaminathan.”

Swaminathan’s daughter Sowmya, a renowned scientist, stresses: “My father taught me the importance of humility. He said the Green Revolution only came because of the synergy between the scientists, politicians and farmers, describing it as a symphony orchestra.”

Manthan was Kurien’s brainchild and he involved 500,000 farmers. With Rupees each contributed, it was India’s first crowdfunded film. Every actor gave his/her best. Particularly, Smita Patil, the spunky farm woman, who came to the cinema and left like a meteor.

Heading the bunch of young actors was Girish Karnad, who played a veterinary doctor wedded to the ideal of cooperation among farmers. Many thought he portrayed Kurien, an engineer who strayed into harnessing milk production and distribution in a milk-starved country.

The ‘green’ one has pulled India out of the shame of food shortages and dependence on free foreign food, like the one the United States sent under its law, “PL-480”. Today, India tops in many farm products, exporting them, and even having the means to import when needed.

India is the world’s highest milk producer, contributing 24.64% of global milk production in 2021-22. At over 220 million tonnes, it is a six-fold growth since the 1960s. The dairy and animal husbandry sector contributes five per cent to the country’s GDP.

The present generation needs reminding that it did not happen overnight.

Sadly, farming and dairying cooperatives, launched in the last century, have been taken over by politicians with little faith in the concept. Values and priorities have changed. The private sector and multinational corporations have stepped in.

Lastly, when Swaminathan was awarded Bharat Ratna, the country’s highest civilian award, nobody thought of bestowing the same on Kurien.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com