The record of Pakistan’s top judiciary may have been more chequered than in many other countries. However, even though it validated the martial law imposed in the past after the military seized power, citing the “doctrine of necessity”, it has also righted many wrongs of the civil and military governments. Now, it has a task on hand.

Among its epoch-making actions will be the manner in which the Supreme Court took suo moto notice of the dismissal of the no confidence motion against the Imran Khan Government in the now-dissolved National Assembly on April 3.

Going by reports, within minutes of these developments, Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Umar Ata Bandial, had the Supreme Court opened on a Sunday. He constituted a three-judge bench and directed that all orders and actions initiated by the Prime Minister and President regarding the dissolution of the National Assembly will be subject to the court’s order.

They include National Assembly Deputy Speaker Qasim Suri’s order, followed by President Arif Alvi’s ‘approval’ of the Prime Minister’s ‘advice’ to dissolve the legislature. The entire process is now open to legal and constitutional scrutiny.

The court took note of the Opposition complaint and a petition of the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA) and gave notice to the government officials concerned.

The apex court had earlier returned to the government a presidential reference on the powers of an elected lawmaker to vote against his/her party. Although it did not say so, it was a clear misreading of the relevant provision by the government meant to brow-beat dissident lawmakers.

To deal with this full-blown constitutional crisis, the apex court has constituted a full bench. While it is too early to comprehend the legal and constitutional complexities, with this turn of events, a veritable debate has been opened that would impact, for now and for the foreseeable future, Pakistan’s polity.

There will be no government worth the name. Its actions, aimed at winning the next election, whenever it takes place, will place various state institutions under pressure to act in a partisan manner and only add to the political turmoil.

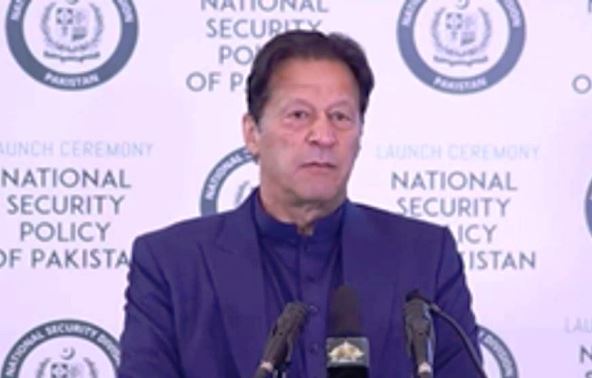

At the centre of it is a renowned cricketer of yore who entered politics to remove corruption and give the country “Naya Pakistan.” The man who promised to “play till the last ball,” tried to run away with the ball when the parliamentary match was not going his way. His hubris has done in, not just him, but also the country.

There are many reasons Khan cannot return to power. For one, he has annoyed and embarrassed the all-powerful army, his mentor and benefactor that put him up as a proxy. He has named the top brass which, having tired of him, sought to caution him, but failed.

It has brought no credit to Pakistan’s only organised institution, called ‘Establishment’ by Khan and anyone who wants to use an honorific, leaving it vague, yet obvious. The army, by its silent neutrality, has indicated its regret at having installed him in the first place as its proxy – Ladla in the local lexicon that means a favourite.

ALSO READ: Imran – Between Hardliners And A Hard Place

This crisis is as much a lesson for this elephant in the room, but to no avail. Pakistan seems destined to be ruled, remote-controlled by the men in khaki who use pliable politicians in colourful headgears. Together, they must stay on the right side of the conservatives and the clergy and appease the “state assets” among the militants.

So, to use a well-known phrase, Army and Allah are sought to be kept “on the same page.” But what about the third ‘A’?

By repeatedly alleging “foreign conspiracy” behind the no-confidence move against his government, and naming the United States, even the State Department official who allegedly conveyed a ‘threat’, Khan has deliberately kicked up a diplomatic row. He has played to the anti-American gallery, hoping to win votes in a future election. He has talked of being thwarted from pursuing an ‘independent’ foreign policy. In popular imagination, jingoism against the US, India and Israel, and ultra-nationalism tantamount to independent foreign policy.

The hard fact is that Pakistan’s feeble political elite, remote-controlled by the military, has pursued nuclear programme and more, but has failed to evolve political stability, set up institutional watchdogs and create a self-sustaining economic base to be able to run an independent foreign policy.

Annoying the US, Khan plans to fight another day, but that has not happened in Pakistan. Recall Benazir Bhutto’s failed attempts to get close to Washington. Neither the US, nor the Pakistan Army that retains tremendous goodwill among the US decision-makers – and benefits immensely – may want to touch him.

Whatever the Supreme Court’s verdict, elections are inevitable. But those that are ranged against Imran Khan today must await another Laadla. The next premier will be in a similar position as Khan found himself in, part of it his own making: high inflation, low prospects for sudden economic turnaround, and a complicated international political economy. The “iron brother” cannot be of much help in this.

That prime minister, and those that come in foreseeable future, will have to contend with the realities of an overpopulated, under-educated, poorly-led and a citizenry easily misled in the name of faith. All political parties need to learn that spouting speeches that begin with promises and end with petulance cannot suffice.

What is in it for India? Almost nothing till Pakistan’s elections are over. Much will depend upon the next prime minister and the elbow-room he/she enjoys with the army.

Nobody can afford to get friendly with India. Forget a civilian, even Musharraf’s downfall began with his controlling cross-border movement and resumption of trade, including films, with India.

The core foreign policy issues including India, Kashmir and Afghanistan, shall remain in the military’s domain. All Pakistani PMs have blown hot and cold with India, and this is destined to continue. A semblance of bilateral trade and cooling down of daily tensions would suffice.

But this suits India, too. Under Modi, it has decided to pursue a tit-for-tat policy. Although conscious that the army actually rules in Pakistan, India, like the western democracies, finds it convenient to respect the democratic fig-leaf and is averse to even open a dialogue with the Pakistani military brass.

On the hand, there are unlikely to be any candle-light vigils on the India-Pakistan border. India’s Left-Liberal sentiment of ‘strengthening’ Pakistan’s democracy itself needs viewing by candle light. It has retreated before an aggressive right-wing dominance where every Indian Muslim is a “Mian Musharraf”. This, too, is likely to continue – so for the time being forget “Aman Ki Asha.”

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com