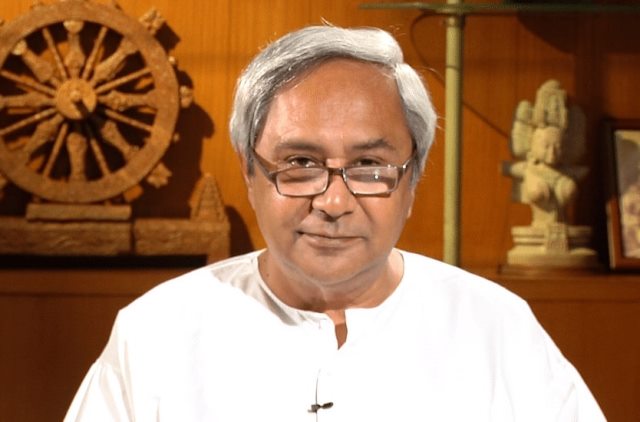

Who is this Naveen Patnaik? An accidental politician thrust into the office of chief minister of Orissa (since renamed Odisha) to fill a vacuum created by the demise of Biju Patnaik, a larger than life man seen as the one who dreamed of a modern industrial state or one by choice who believed that nothing of substance would happen to the state unless the malady of corruption was rooted out and the administration was rid of slothfulness? Patnaik had occasions to say that he would have loved to spend his life as a writer – incidentally, his elder sister New York-based Gita Mehta has to her credit books such as A River Sutra, Karma Cola and Snakes and Ladders: Glimpses of Modern India – but then “you find me in this role.”

Three years after founding the Biju Janata Dal (BJD), Patnaik first became chief minister of Orissa in 2000 and has won all the five Assembly elections with impressive margins to remain the country’s longest serving state government head with a kind of record that is envy of every other CM. What distinguishes Patnaik is his relentless campaign against corruption. He remains ruthless in ridding ministers and bureaucrats found indulging in making deals at the cost of the state. This crusading zeal sadly missing among most present day politicians is one of the two considerations of investors; the other is making the bureaucracy energetic enough not to sit back on investment proposals, for fancying Odisha.

A corruption free (at least to the extent that investors are not complaining about any favours they might be giving for work to be done) administration is never enough to attract investment. Among the other more compelling requirements are the quality of infrastructure, raw materials availability and supply of skilled manpower. The credit goes entirely to Biju Patnaik, the architect of a modern industrialising Odisha, that the state owns all-season, deep-draft Paradip Port, which last financial year handled a record cargo volume of 116.13 million tonnes. The big risk taker and visionary that he was, Biju Patanaik brushed aside the Centre’s objection to finance Paradip Port project and mobilised the resources on his own to give shape to his vision. The port was commissioned in March 1966, giving the state crying for industrialisation, a major break in infrastructure and logistics. Odisha saw commissioning of another major all-season, deep-draft, multi-user port when Tata Steel in equal partnership with engineering behemoth Larsen & Toubro commissioned the Dhamra Port at Bhadrok district in May 2011.

An example of the growing pull of Odisha among big ticket investors was the Adani Group taking over the port in May 2014 and now working on an ambitious plan to speedily ramp up cargo handling capacity to 300 million tonnes in phases. The state has several other minor ports, including one at Gopalpur. This is as it should be since the state has a coastline of around 450 kms. Paradip Port is the reason that in an adjacent area Indian Oil Corporation built a 15 million tonne refinery at an investment of ₹34,555 crore.

A senior Bhubaneswar based editor of an Odia daily says: “Biju Babu used to say prosperity will remain elusive unless we have industries. In pursuit of industrialisation, he wanted his bureaucrats to stop indulging in writing long notes. Instead, he wanted them to become agents of change, particularly in creating an investor friendly environment. Not only has Naveen acquired that trait of his father, but he has gone a step forward in demanding of them to deliver results without anyone pointing a finger at them. Big man Biju Babu was forgiving in many ways. Naveen has zero tolerance for corruption and also for incompetence. If you ask me I will say Naveen’s approach to administration has brought a breath of fresh air in national politics.”

Unlike many opposition leaders, including West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee, Naveen hasn’t so far betrayed any national ambition. His focus remains to place Odisha among the country’s highly industrialised states, based largely on its rich mineral resources. No doubt, Naveen is succeeding in reaching that goal. He has also stood out among opposition stalwarts in another way. Being a believer in the country’s federal system, he doesn’t think it proper to go out of the way to criticise either prime minister Narendra Modi or the union government. That way he commands the respect of people at large. Investors in particular don’t want to be caught in the cross fire of centre-state quarrels. His clear instruction to his ministers and senior bureaucrats is that in case they have a problem with the centre, then they should make all efforts to resolve it through discussion instead of making it public at the outset.

Naveen expectedly campaigned hard during the 2019 assembly elections that coincided with the Lok Sabha poll crisscrossing the state. As has now become the norm in all opposition run states, it is on the strength of popularity of the chief minister that candidates of ruling party BJD secures votes. In the last elections, BJD won 112 of 147 seats, albeit down five seats over last time. What distinguished Naveen’s campaign was that he never foul-mouthed Modi. He is too civilised to come down to that level. Critics will say Naveen’s realpolitik is based on practical consideration and it has got nothing to do with ideology or principles. Whatever it is, this honourable disposition of the chief minister may be the reason why central clearances for projects relating to Odisha generally come through in time.

Ports are one component of infrastructure. But Odisha being India’s most minerals rich state, ports provide a gateway for exports of iron ore, bauxite (alumina), ferro-alloys, etcetera and also ex-im of several minerals, either not found at all such as nickel or not in sufficient quantities such as metallurgical coal and metals. In the past decade and a half, Odisha has made impressive strides in building multi-lane highways. But what the state urgently needs is much improved railway network and rakes availability. In the past many years, power plants, including the ones captive to industries such as aluminium smelters, ferro-alloys and steel had to do with restricted supply of coal because of rake shortages and production disruptions at coal mines during the monsoon. A feeling prevails in the state that since the railway minister Ashwini Vaishnaw, a retired Odisha cadre IAS officer, has good appreciation of the state’s requirements of rail services, rapid improvements are to happen. Air connectivity between the capital city Bhubaneswar and the rest of the country continues to improve with more flights being added periodically.

Investors are basically eyeing the state’s rich mineral resources for processing into metals. Tata Steel is here for a very long time as producer of iron ore. But for some years, it is running a steel mill at Kalinganagar, which is being substantially expanded to 8 million tonnes. The Jindal family through JSPL has a large carbon steel plant and through JSL the country’s largest stainless steel unit in Odisha. The largest Jindal family controlled JSW Steel has in the meantime received environmental clearances to set up a greenfield 13.2 million tonne mill at Paradip at an estimated investment of Rs65,000 crore. Now ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel joint venture proposing an investment of over 1 lakh crore to build a 24 million tonne steel mill in Kendrapara district has the promise of a unique venture in terms of size, promising to be the world’s largest single location plant and use of green technology. The chief minister himself has played an important role in bringing the project to Odisha.

The Adani Group has readied investment of Rs57,575 crore to build a 4 million tonne alumina refinery and also a 30 million tonne iron ore project along with commitment to use as much green energy as possible. Anil Agarwal shepherded Vedanta Group, which already has a massive presence in the aluminium chain in Odisha is once again investing Rs25,000 crore for capacity expansion in white metal and ferrochrome. Besides minerals-based industries, the chief minister wants Odisha to become a major destination for small and medium enterprises adding value to locally produced aluminium and steel. National Aluminium Company is soon to commission an aluminium park at Angul where the units will have the benefit of supply of molten metal from the next door NALCO smelter. Like that a park for plastic products will be built. Leave aside industries, the capital city Bhubaneswar, expanding in all directions, is fast emerging as an important hub for education and health, in a way taking the wind out of Kolkata’s sails.

As most of the promised mega, medium and small projects are being implemented, the state though now self-reliant in electricity will have to create new power generation capacity. Being richly endowed in thermal coal, the natural tendency will be to build coal-fired electricity capacity. Mercifully, Patnaik has set his priorities right in inviting investors to derive energy from green sources such as solar, wind and mini and micro hydel units. The sun shines bright on Odisha for most of the year and it is also blessed with a long coastline. Therefore, building solar and wind energy is not a big challenge for the state. The installed power capacity in Odisha in 2021 March end was 8,594 MW out of 382 gigawatts for the country. People caring for the environment will expect Naveen Patnaik to secure sufficient private investment in all forms of green energy so that pollution caused by burning of coal is capped at a certain level.

Read More: http://13.232.95.176/