Blood like water spilt in the dust… And, with the first light of morning, he saw the truth… He took a handful of blood-soaked earth in his hand, heavy and black, and rubbed it against his forehead… and he swore a terrible vow… No matter how long it took, no matter how it took him… he would track down the dogs who did this to his people and he would kill them…

– The Patient Assassin: A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and The Raj by Anita Anand (Simon and Schuster, UK, 2019)

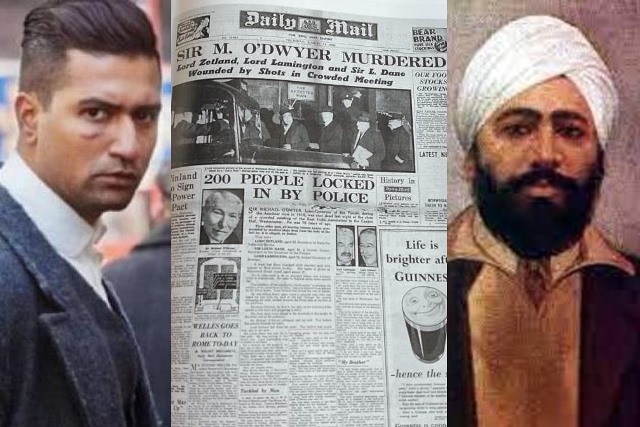

Filmmaker Shoojit Sircar makes deeply meaningful films, which break the blurred lines between the parallel and mainstream cinema. He has made significant films like Vicky Donor, Gulabo Sitabo, October and Pink. His latest is an epic on a difficult and fascinating subject – Sardar Udham. The film is being premiered on October 16.

In the words of Sircar, ‘‘He was definitely an adventurer, and he was focussed. The film zooms into Udham’s mind. We have tried to understand what he was keeping to himself, that mysterious thing he was carrying; what was his belief system, his ideology; how did he travel, because there was a lookout notice on him and he could not take the sea route…Yet he did. He was a member of the Ghadar Party in America. He was a small-time actor, a mechanic. But he was not known at all till the news of the assassination broke out in 1940. There are many missing links. I have presented as much as I know, but I also don’t know everything.’’

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre was systematically executed on April 13, 1919, as thousands of peaceful protesters gathered in this sprawling and dusty walled space in Amritsar. No one could imagine or anticipate what would follow on that fateful and tragic day. The armed troops moved into the narrow lanes, took positions and started firing almost immediately, one round after another.

People fell soaked with blood. People ran and fell, dead and half-dead. People were buried under the dead, some still alive and bleeding. No one was spared, not even children. This was perhaps one of the most cold-blooded massacre to ever happen in the history of the colonised world.

The firing was executed with single-minded motivation by Brigadier General Reginald ‘Rex’ Dyer. He was following the orders of Lieutenant Governor Michael O’Dwyer, who had by then established himself as one of the most ruthless and racist administrators in British Punjab. Both expressed no regrets for this mass murder ever in their life.

The massacre led to outrage across India. It created waves of protests. Revolutionaries moved across the landscape spreading the idea of revolution. There were intelligence reports of entire Punjab being up in flames and spontaneous violence against the British was being anticipated.

In retaliation one village was bombed. Soldiers shot dead farmers returning from the fields and inside their homes from an aircraft. Youngsters were flogged in public places in Amritsar for no rhyme or reason. Others were compelled to lie flat on the ground on their chest and crawl for long distances, while being whipped and kicked. There was no time for mourning and shared grief. One wave of vengeance and violence followed another wave under the brutish regime of Michael ‘O Dwyer.

This is where the true and mythical story of Udham Singh begins, as depicted with great historical detail in a classically lucid and wonderfully penned book on his life and times by Anita Anand. Her grandfather was present in Jallianwala Bagh moments before the killings began. Her book is a painstakingly researched narrative across several countries, including from the nooks and corners of Punjab.

The new film would therefore be a great leap of imagination, with cinematic possibilities. This is simply because so little is known about the many fascinating layers which makes the character of Udham Singh. It would be an epical task to measure and map the kaleidoscopic spectrum of the life of this colourful, brilliant, non-conformist and totally unconventional revolutionary who worked for years with the underground Ghadar Party, literally, across the world.

Udham Singh was born as Sher Singh in a poor family in a village in British Punjab. His mother died very young. His starving and hardworking father too died on the way while walking on a long trek with his little sons, Sher and Sadhu Singh, to Amritsar. According to Anita Anand, some priests who were passing by picked up the children and handed him over to a distant relative, who, then, put them up in an orphanage in Amritsar run by a kind and generous Sikh.

ALSO READ: An Idea Cannot Be Jailed

No one really knows for sure the whereabouts of Udham Singh when the Jallianwala Bagh massacre happened. Among the many narratives bordering on mythology involving his life, it is said that he was on the spot when the massacre was executed by the ‘butcher of Jallianwala Bagh’. And he survived.

He thereby picked up a fistful of blood-soaked earth from the ground, and vowed to kill the man responsible for the massacre. And then he waited, schemed and planned. From a poor and homeless orphan, and a jobless, starving youth, his life is truly a classic epic of struggle, resilience and flight of imagination.

From a lowly worker in the Ugandan Railway Company to Basra and Baghdad, from Mexico to the United States of America, crossing illegally across the border, from travelling across the length and breadth of American states to land up in New York, and then travelling across Europe, and, finally, to London, it was an eventful journey for Udham Singh. He changed his name and identity several times, even while working overground and underground as a Ghadarite, transporting revolutionaries across borders, funding armed networks, procuring arms and ammunition, distributing incendiary literature against the British. In between he was arrested in Amritsar with guns and ammunition in his possession. He was brutally beaten up and kept in solitary confinement because he would campaign among the prisoners against the British. Then he was transported to Mianwali Jail (now in Pakistan’s Punjab).

This is where he met and came to know another legend and intellectual: Bhagat Singh. Clearly, when Bhagat Singh was hanged, it shocked Udham Singh to the core of his heart. Himself an illiterate, henceforth, he called Bhagat Singh, many years younger to him, as his Guru.

Despite this incredible full-time revolutionary work, interspersed with a marriage with perhaps a Mexican woman in America and a regular family life for a short spell, he finally fulfilled his pledge to himself, to the murdered people in Jallianwala Bagh, and to his country’s freedom. It was a long wait.

In a meeting organised by the East India Association in London, Udham Singh pumped several bullets inside the body of Michael ‘O Dwyer at the dias on March 13, 1940. He had taken his revenge after 21 years. During interrogation, he said his name was Mohammad Singh Azad – a secular pluralist revolutionary celebrating the freedom of his country from the yoke of colonialism.

The murder of ‘O Dwyer created waves of celebration across India and among Ghadarites, revolutionaries and freedom fighters. To stop the message to spread through a public trial, the British acted swiftly. Udham Singh was hanged on July 31, 1940, at Bradbury, England. His remains have been preserved at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar.