I had a dream.

–From The Vegetarian by Han Kang

South Korea is not only known for K-pop, or its electronic goods, in what is a modern, western-style, liberal capitalist democracy with American troops stationed in its backyard. It is also known for the infinite suffering of its girls, young and older women. Their suffering is beyond imagination.

The Imperial Japanese Army occupied it, using relentless, savage, bestiality, from 1910 to 1945. Soldiers would randomly pick up little girls or women from the streets, or homes, and then they would simply disappear.

The fact is thousands of girls and women were forcibly abducted and trapped forcibly in multiple hell-holes, in abysmal, unhygienic conditions, and brutally raped, non-stop, by Japanese male soldiers — for days, months, years. One survivor later testified that “not one minute would pass” — and she would be, yet again, savagely assaulted by the men. Again and again.

Branded ‘comfort women’ and legitimized by a nasty and pervert King Hirohito, who aligned with the fascists during World War II, only a few survived this life-time of sex slavery. No justice has reached them till now, neither has an authentic regret seemed to have passed the lips of the successive Japanese governments which followed the war.

Hirohito’s army’s barbarism is unimaginable. They are also infamous for what is called ‘The Rape of Nanking’ (Nanjing), then the capital of ‘Nationalist China’.

Widely documented, it is believed that in 1937, over a period of merely six weeks, the Japanese army raped/gang-raped tens of thousands of girls and women, and then murdered many of them in the most grotesque manner. Hundreds of thousands of ordinary people were butchered. Nanking was ravaged. Many Chinese women then found themselves trapped in the same hell-holes in Japan, as the brutalised sex slaves of South Korea.

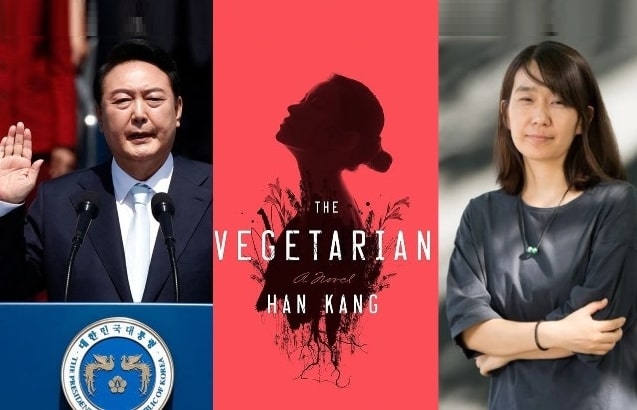

The people of South Korea recently refused to accept martial law and dictatorship being imposed by a discredited and corrupt president, who has been hitherto an American lackey, and a darling of the US establishment. People have thronged the streets in Gwangju, Seoul and elsewhere, in protest, defending their democracy. Since then the president has been impeached and stripped of all powers. He can’t even travel out of the country. And in case found guilty after a trial, he may even face a death sentence — in South Korea, the head of State has no immunity.

In her book The Vegetarian, Han Kang tells us how the male gaze and male power (for instance in a marriage, or, inside a so-called ‘happy family’) is integral to the entrenched masculinity of patriarch, in what appears to be a modern, liberal society. The protagonist, a slender, sensitive and quiet woman, not at all self-conscious of the innate beauty of her mind, and her body, suddenly stops eating meat. She says, in explanation, that she has seen a dream. (The dream is replete with blood, flesh, meat, death, decadence, grotesque hedonism. It is a kind of revelation.)

So, in a staged family dinner, her father stuffs meat in her mouth, repeatedly, while her mother, sister, husband, sister’s husband, they all watch in silence. Home suddenly turns into a suffocating prison, a torture chamber. She still refuses to eat meat.

Her father stuffs more meat in her mouth. Repeatedly. She pukes it all out. Then he slaps her.

Her husband, a meaningless, clerical creature, narrates, “…in the instant that the force of the slap had knocked my wife’s mouth open, he’d managed to jam the pork in. As soon as the strength in Yeong ho’s arms was visibly exhausted, my wife growled and spat out the meat. An animal cry of distress burst her lips.”

“Get away!”

She picked up the kitchen knife. “Jaw clenched, her intent stare facing each one of us down in turn, my wife brandished the knife… Blood ribboned out of her wrist. The shock of red splashed over white china. As her knees buckled and she crumpled to the floor…”

Clearly, this is not the first time that she has been violently attacked by her father. As her elder sister tells in the last chapter, this was an everyday reality in the childhood and youth of her little sister, Yeong-hye.

ALSO READ: Daughters Against Dictators

One of the reasons this South Korean president was elected, I am told, is because a large chunk of men voted for him — in protest against the rising power, stature and dignity of women in public spaces and organisations. They hate women who don’t toe their line. And they want women to be as subservient, obedient and crushed, as was the protocol earlier.

Much before the latest mass protests, Han Kang suddenly emerged in our stream of consciousness like a quiet evening star twinkling in a twilight of gloom and doom. A South Korean novelist, she was given the Noble Prize for Literature for 2024 for her “intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life”.

Named after the Han river, she was born in the winter of 1970 in Gwangju, which led the first, massive, people’s uprising against the military dictatorship in1980, which rocked South Korea and ushered in democracy and freedom. Hundreds were butchered by the army, women assaulted, students killed in cold blood. But the people refused to be defeated; they picked up arms. They fought on the streets, in campuses, schools, lanes and bylanes, from inside homes. And they won!

I was invited to Gwangju almost 20 years ago to write about the nightmares, the memories, the tributes and the celebrations. I travelled on road from Seoul to Gwangju. I met, mostly, beautiful young men and women, so friendly, that one female college student, who was my guide, held my arm all the while she showed me a gallery of remembrances. In the market place, I asked two college girls about their memories. They took me to a cafe, and told me stories they had heard when they were kids. One of them had streams of tears falling down her face.

A society which forgets its great actors of resistance, will rot and repent. Not in Gwangju! Here, the memorial of the fighters is not ‘a graveyard of the dead’. It is a living testimony of gratitude. A photo, a living flower, a brief introduction adorns each grave, shaded with trees. Unknown visitors cry for unknown people, bent low in respect, touching their photos. Tears float on the pictures, like dew drops on the flowers. Han Kang’s book, Human Acts, which I am now reading, tells the Gwangju story.

(One can see the cracked mirrors of contemporary India, and a shiver runs down the spine. This country seems to have lost all its memories of the great sacrifices done by our revolutionaries and freedom fighters, many of them tortured, imprisoned and hanged. Plus, the killings. Remember the Jallianwala massacre?)

Based on an earlier literary work, The Fruit of My Woman, whose title tells a tale, Han Kang wrote The Vegetarian when she was in her early 30s. Meat is a metaphor in her book. So is fruit.

The book, lucidly translated by Deborah Smith, got her the International Booker Prize in 2016. And, then, suddenly, Korean literature seemed to have become the flavour of the world.

Author Ellen Mattson, a member of the Nobel Committee for Literature, said during the award-giving ceremony on December 10, 2024: Two colours meet in Han Kang’s writing: white and red. The white is the snow that falls in so many of her books, drawing a protective curtain between the narrator and the world, but white is also the colour of sorrow, and of death. Red stands for life, but also for pain, blood, the deep cuts of a knife. While her voice can be seductively soft, it speaks of indescribable cruelty, of irreparable loss. Blood flows from the bodies piled up after the massacre, darkens, becomes an appeal, a question that the text can neither answer nor ignore: how should we relate to the dead, the abducted, the disappeared? What can we do for them? What do we owe them? The white and the red symbolize a historical experience that Han returns to in her novels.”

Indeed, in Yeong-Hye’s dream, we share our hidden longings and sensuality. In her shackled freedom, we can feel our own unfreedom. And in her refusal to eat meat, we can taste in our mouth, and in our deepest desires, the forbidden fruit, eternally denied to us.