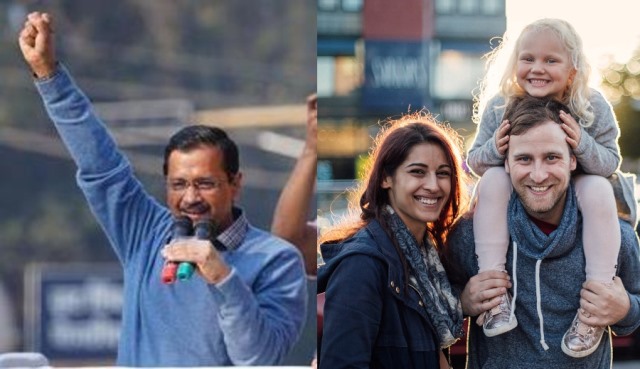

At 53, by the standards of Indian politics, Arvind Kejriwal has a lifetime ahead of him for his political career. But already he has made impressive strides. Currently serving his third term as chief minister of Delhi, Kejriwal and his party, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) recently swept the elections in Punjab, recording a historic event in Indian politics by a relatively small regional party, long confined to only Delhi, to spread its wings to another much bigger state.

Under Kejriwal’s leadership, AAP’s trajectory in Indian politics has been controversial. A civil servant with an engineering degree from the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, Kejriwal turned to political activism and then joined a nationwide movement against corruption. Then, in 2012 he formed the AAP to contest elections in Delhi. AAP won the Delhi elections three times and Kejriwal has since then established his party’s dominance in that state.

The victory in Punjab, however, marks his party’s move to other states and can be considered as a stepping stone to establish the party on the map of national politics. What works for AAP is the party’s demonstrated commitment to clean politics and accountability. Unlike other national parties that have traditionally formed governments in the state of Delhi–the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)–AAP has provided citizens with tangible results. Delhi’s schools, mohalla clinics, water and electricity supplies, especially for the poorest, have all significantly improved during AAP’s tenure.

Not surprisingly, such focus on the “aam aadmi” or common man has ensured that his party gets the mass support that it has consistently in Delhi and now in Punjab. AAP contests elections by talking about promising improvements on basic local issues. Its rivals such as the Congress and the BJP, on the other hand, either push personality-driven campaigns or ones that are less granular when it comes to improving people’s lives.

As the AAP victory in Punjab shows, the ordinary voter is tired and sometimes even fed up with so-called career politicians that lead the older, national parties. To many of them, AAP represents a breath of fresh air–a political party that identifies with their real needs. The question, however, is whether Kejriwal and his party can leverage this image to make a mark on national politics. Could Kejriwal become an alternative to, say, a national leader such as Narendra Modi?

You could say it is too early to pitch Kejriwal as an alternative to Modi but in Indian politics, nothing is impossible. Nothing can be ruled out. AAP’s storming of Punjab bears testimony to that. The next parliamentary elections are due in May 2024, which is barely two years away. Before that, later this year there will be elections in Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat. Next year, there will be many other states where elections will be held, notably Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan (but also in Tripura, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Karnataka, Mizoram, and Telangana).

If AAP has a gameplan to spread its wings wider, it could, at least in theory, surely focus on states such as Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan. These are in a manner of speaking low hanging fruit that the party could focus on. All three are states where the majority of the population is poor and under-privileged, which is quite clearly the groups that AAP targets not only in its campaigns, but also by way of the policies that it adopts–its achievements in Delhi are evidence of that. If AAP can make inroads in these three states (and it already has Delhi and Punjab), could it not be a force to reckon with when the parliamentary elections are held?

You could call it wishful thinking but consider this: on the horizon of national politics in India, there is a dearth of alternatives to the BJP and to the towering image of Modi. The Congress is a faltering shadow of its past, unable to win elections, either in the states or nationally. The other regional parties, be it those that run states in the south such as the DMK in Tamil Nadu, or in the east such as the Trinamool Congress, may have charismatic leaders such as M.K. Stalin and Mamata Banerjee, respectively, but till date they have not demonstrated the prowess required to spread their electoral wins beyond their regional fiefs. Against that background, could Kejriwal and his party stand apart as a future alternative to the BJP at the Centre? It could be a point to ponder.

Happiest Nations Of The World

For five years, a popular survey has ranked the tiny Nordic country of Finland (population 5.5 million) as the happiest country in the world. Finland, along with other Nordic countries are at the top of that ranking list consistently. What makes people in nations such as that feel “happy” is a bunch of things but mainly these: a robust social welfare system, low crime rates, an abundance of natural beauty, an emphasis on community and co-operation, universal health care, and very few people living in poverty. These factors are taken so much for granted in, say, Finland that people living in that country are often bewildered why their nation is ranked as being the happiest!

At the other end of the ranking, the picture is grim. Afghanistan ranked the lowest among the 149 countries surveyed. Ravaged by wars and the recent return of the Taliban regime, its performance in the survey should not come as a surprise.

But it is India’s performance that should be of grave concern. India hasn’t fared much better than Afghanistan. It ranks at 136 among the 149 countries. China with which India likes to compare itself ranks at 82. The USA is at 19. And even Pakistan at 103, and Bangladesh at 99 are higher than India.

Surveys come with caveats such as small sample sizes, biases, and other inaccuracies, but if the people of a country perceive themselves as being so unhappy, isn’t it time for the government to take note and address the problem?