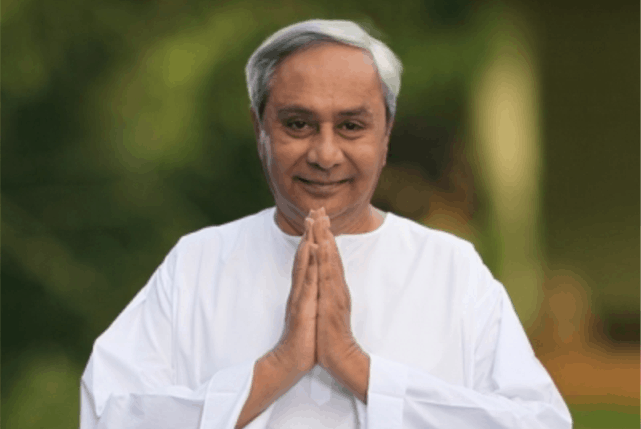

In elections such as the one that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won spectacularly in India recently, it is not always easy to zero in on a single person’s contribution to the victory. India’s electorate is massive (830 million people were eligible to vote in the recent polls); and it is diverse, spanning different demographics, cultures, languages, and socio-economic classes. Yet, one man’s contribution to the tsunami-like wave that gave the BJP 303 seats out of Lok Sabha’s 543 clearly stands out. And that is BJP’s president (and now India’s home minister), Mr Amit Shah.

Mr Shah is often described as being his party’s master strategist, a doer who is single-mindedly focused on tasks that are prioritised for him by his party and his leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In 2014 and 2019, that task was of winning the parliamentary elections. In both those, he excelled. He went about those tasks with meticulous planning and discipline, transforming the party into a well-oiled machine that has a dedicated, loyal, and hardworking cadre of workers at every echelon—from the national level; the state-levels; and down to district levels—across India. No other Indian political party has the sort of structure that the BJP, particularly its electioneering machinery, has.

Mr Shah’s efforts bore fruit. The BJP, which was considered to be a party whose support base was predominantly in the north, central and western India, has now spread its influence and garnered support in the east. In Bengal, in the 2019 elections, it won 18 seats out of a total of 42, a feat that surprised many analysts who may have been of the belief that the eastern bastion couldn’t be breached by the saffron party. The 303 seats that the BJP won show that its span of influence now covers much of India, except perhaps the south where it is still considered a northern party of Hindi-speakers and where regional parties dominate the political landscape. Yet, in the southern states, which account for 130 seats, the party and its allies won 30.

Mr Shah cut his teeth in politics in his home state of Gujarat where notably his tenure as home minister was marked by several controversies that led to skirmishes with the law (he was arrested and jailed in 2010 in connection with an alleged fake encounter killing by the police that had taken place when Shah was the state’s home minister). But when Mr Shah was inducted to the upper house of India’s Parliament in 2017, Prime Minister Modi is believed to have told his party’s legislators: “Amit Shahji ke (Parliament mein) aane se aap ke mauj-masti ke din samaapt ho gaye hain.’’ (After Amit Shah has come to Parliament, your days of fun and relaxation are over). That probably is an apt indicator of the kind of political leader Shah is: a highly motivated, result-oriented taskmaster who doesn’t shy away from being tough.

As home minister, Mr Shah will have lots of opportunities for big tasks and equally big challenges. Topmost on his agenda could likely be Jammu & Kashmir where there has been no elected government in charge after the coalition between the BJP and the regional People’s Democratic Party (PDP) broke down and the government collapsed. Elections in the troubled state have not been held as militant separatists are still active and terrorist attacks from across the western border with Pakistan have far from abated. The trouble in Kashmir, which enjoys several autonomous rights that are different from other Indian states, has been festering for more than two decades, and a solution has eluded most government regimes at the Centre. Bringing peace back to Kashmir and ensuring that elections can take place there peacefully is something that will test Mr Shah’s skills to their limit, yet many think that he could probably be the only person in Mr Modi’s government decisive enough to find a solution in the state.

Before the elections were held this year, the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was introduced in Assam with the objective of screening out illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and other neighbouring countries and find ways of repatriating them to their countries. It is a controversial move, but Mr Shah is a strong advocate of it. The problem of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh or other places is, however, not restricted to Assam. Other eastern states such as Bengal, Bihar and Odisha are equally affected by such influxes. And, illegal Bangladeshi immigrants exist all over India, notably in northern India. Mr Shah could possibly think of extending the register now being implemented in Assam to other states. That sort of a move would likely invite opposition and controversy, especially regarding the possibility of its misuse, but those are things that have rarely bothered him.

Mr Shah’s main advantage—besides his amply proven skills as a strategist and implementer—is the full backing of Prime Minister Modi that he enjoys. The two men enjoy a chemistry that is rare in political relationships. Mr Shah has been Mr Modi’s trusted lieutenant since the latter’s innings as chief minister in Gujarat. And, thereafter, when he was the prime ministerial candidate in 2014, as his chief election strategist. Later, after he became president of the party, Mr Shah and Mr Modi worked in tandem. The pair have been highly effective as the results of the 2019 elections demonstrated recently. Many believe as home minister, Mr Shah will wield more power and have greater clout than any other cabinet minister in Mr Modi’s government.

The other task that Mr Shah will have will be to quash extreme leftist militancy in parts of India, particularly in Chhattisgarh but also in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Left extremist hideouts in these regions have been a tough nut to crack for successive previous home ministers and, although attacks and ambushes on security forces aren’t frequent, when they occur, they take a heavy toll. In early May this year, more than a dozen security personnel died in Gadchiroli (Maharashtra) and several of their vehicles burnt. These guerrilla-style attacks need to be checked but many believe the root of the problem lies deeper. The regions where extremism thrives are typically impoverished tribal areas and a lasting solution would need to combine both, strikes at extremist groups and implementing plans to improve the lot of the local population in these areas.

Unrest in Kashmir, rampant infiltration from across India’s borders, and left extremist violence have never been easy problems to tackle. Governments in the past, including Mr Modi’s previous regime, have faltered on all of these. It is perhaps with that in mind that Mr Modi anointed Mr Shah as his home minister. If there is anyone who can decisively attempt to take on these challenges, it is him.

]]>