Kashmir is in the news these days for

reasons right and wrong, and promises to persist for long. Pakistan is most

upset with India’s nullifying the special status under Article 370 of the

Constitution. It calls Kashmir “unfinished part” of the 1947 Partition.

But now it is being asked: was it part of

the Partition at all?

New research points to the British introducing

it after the Congress abandoned its government in the North West Frontier

Province (NWFP) (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) and also conceded Balochistan.

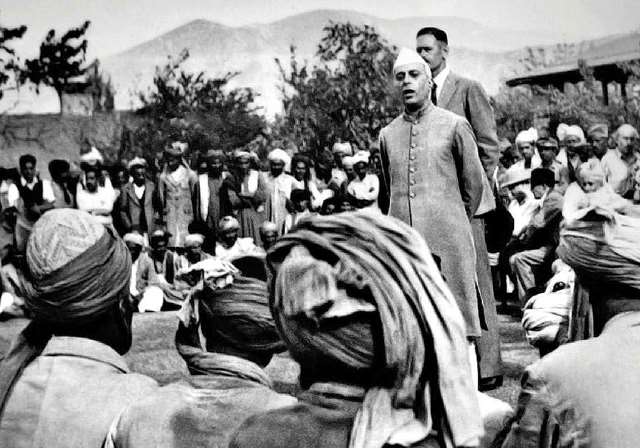

Old records show the British, after

reaching an understanding with the Muslim League, coaxed Jawaharlal Nehru to visit

NWFP which the latter did despite opposition from Sardar Patel and Maulana Abul

Kalam Azad.

Most crucially, ‘Frontier Gandhi’ Abdul

Ghaffar Khan and his brother and the province’s Chief Minister, Dr Khan Saheb, were

not consulted, when they ran a “strong’ Congress government.

Raghavendra Singh, a retired civil servant

while dwelling on his book, “India’s Lost Frontier: The Story of the NWFP

Province of Pakistan, ” says that Nehru made the “fatal mistake” of visiting the riot-hit province with approval of then

Congress chief Acharya Kripalani and agreed to an election and later, a referendum.

The ministry had to resign.

Once Ghaffar Khan and his Khudai

Khidmatgar were “thrown to the wolves” (in their words) the British found it

easy to include Balochistan in the south and Jammu and Kashmir in the north to

be incorporated into the future Pakistan.

Citing correspondence among the top

British rulers in New Delhi, the British Government and records of the Department

of Commonwealth Affairs of that era, Singh says: “The British approach

radically changed in 1946, soon after the end of the World War II. Lord Louise

Mountbatten was sent as the last Viceroy “only to complete the formalities.”

He rejects the principle of contiguity of

the two provinces that the British insisted upon. But for the ‘sacrificing’ of

NWFP and Balochistan, “there would have been neither the Kashmir dispute, nor lack

of access to Afghanistan that irk India today.”

Respective roles of the British and the

Indian leaders stand in stark contrast. The Congress and the Muslim League were

both part of this as “nobody wanted to go back to jail. They wanted to bury the

hatchet for good. Some Indians with

Western education and sensibilities thought the division was temporary.”

This reinforces what is well-known and

debated ad nauseam. Never the hapless umpire, the British wanted the Partition.

They played the proverbial cat distributing bread among the squabbling monkeys.

They saw Pakistan as their bulwark to

retain their influence in the region and that it would help ‘contain’ the

Soviet spread to the Indian Ocean region. A new chapter of the “Great Game” was

thus written.

In contrast, an independent India, too big

and diverse, was perceived as being not amenable to the West. The British also

wanted to create a Muslim nation to guard their interests with the monarchies

and the oil resources in the Middle East.

They proved right on many counts. The

Middle East saw unprecedented oil boom. The rise of a communist China, in

addition to the Soviet Union posed a bigger challenge. Independent India

empathized with both. They were proved wrong, however, that the British Empire

itself declined, almost totally, within two decades of the Partition.

It’s time to question the inevitability of

the Partition, at least how it was executed. How entire provinces were divided

despite their mixed populations, causing millions to flee their homes amidst

bloodshed – and bad blood that persists today. Neither the British, nor Indians

anticipated this, despite communal tensions.

Opinion is emerging among select Indian

scholars, especially civil servants and diplomacy practitioners who have seen

the world closely. Using British records, it challenges the British-guided

history of the region.

Through them, it is possible to view larger

picture of the South Asian region and also the adjoining West Asia as part of

the “Great Game” that continues to be played through its many avatars.

Also, through them, it is possible to view

many faults and failures of Indian political leadership of that era without

getting embroiled in the current, largely uninformed debate that is besotted

with a political agenda, of deifying some leaders and demonizing some others.

The problem, pointed out by Ambassador TCA

Raghvan, author of “The People Next Door: The Curious History of India’s

Relations with Pakistan” (2017) is that “we view history with contemporary

eyes”.

It is not clear how far the Subcontinent’s

political leaders were able to grasp the larger – regional, if not global –

worldview, of how the European colonizers, having ruined themselves fighting the

World Wars, sought to draw Asia’sn national borders, intent on keeping their

strategic and economic hold. They

didn’t, or at least, not enough. For, all conflicts since then have occurred in

Asia.

India’s division was preceded by a line British

India drew with Afghanistan. Ambassador Rajiv Dogra in his book, “Durand’s Curse – A Line Across

the Pathan Heart”(2017), emphasizes how an invisible, but powerful line (drawn

by and named after British foreign secretary, Sir Mortimer Durand) divides the

ethnic Pashtuns and continues to cause friction between Kabul and Islamabad to

the detriment of both.

To this day, in multi-ethnic Afghanistan,

its dominant Pashtuns nurse an unrealized dream of Pashtun homeland. And to this day, Afghanistan, the graveyard

of many Empires, yet coveted by many because of its location, remains a nation

in perennial turmoil. It is possible to foresee severe instability in

Afghanistan, no matter who rules.

Looking at the larger picture, yet another

Afghanistan sub-chapter in “Great Game” may be written soon with the United

States’ victory-less withdrawal. The Asians will play proxies, and the conflict

will continue.

China, the emerging global power, already embracing

most Asians with its multi-billion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), will be a

significant player, backing its key proxy Pakistan. India may be ‘friendless’, yet

again.

Back to Kashmir: Whatever be domestic

compulsions and consequences, the Kashmir factor that India has introduced also

promises to be part of this larger ‘game.’ The India-Pakistan rivalry will surely

persist. India will not roll back Kashmir’s re-worked avatar and Pakistan will

not countenance it.

Odds are heavy against Pakistan. Like it

could not keep out of the Afghan imbroglio in the past, much to its detriment long-term,

it cannot ignore Kashmir either.

Pakistan’s military-civil leadership now tackle

two-front turmoil of having to secure border with Afghanistan while pushing the

Taliban towards Kabul, and with India — opposition its Kashmir moves while

keeping the Kashmir pot boiling within the country and before the world

community.

Despite pressures from within and provocations from without, India can and may ‘digest’ this if it genuinely reaches out to the Kashmiris. If it fails, not 1947, but the year 2019 will be the base year for future historians.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com